By firing tiny projectiles of iron-carbon alloy from a high-speed cannon, scientists have finally demonstrated that a weird part-solid, part-liquid-like state thought to exist inside Earth's inner core is indeed possible.

This superionic state of matter would neatly explain some unusual behavior in the core, such as the way it slows certain waves, and measurements that suggest it's squishy like butter rather than rigid like cold steel.

"For the first time, we've experimentally shown that iron-carbon alloy under inner core conditions exhibits a remarkedly low shear velocity," says physicist Youjun Zhang of Sichuan University in China.

"In this state, carbon atoms become highly mobile, diffusing through the crystalline iron framework like children weaving through a square dance, while the iron itself remains solid and ordered. This so-called 'superionic phase' dramatically reduces [the] alloy's rigidity."

Related: After a 20-Year Search, Scientists Have Finally Found Earth's True Innermost Core

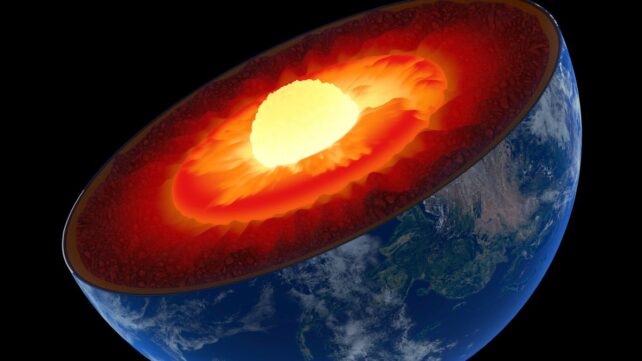

Since the 1930s, the prevailing view of Earth's interior has followed the model of a liquid, molten outer core, and an inner core so crushed by pressure that it remains a solid despite the intense prevailing heat. However, some evidence from seismic data obtained over the decades has hinted that we're not seeing the full picture.

Our understanding of Earth's inner structure comes from seismic observations. The way acoustic waves move through and bounce off materials with different properties has given us a pretty detailed understanding of our planet's internal architecture. But the low velocity of shear waves through the core in particular suggests that if it is solid, it's not in the way that we're used to.

In 2022, a team led by geophysicist Yu He of the Chinese Academy of Sciences theoretically demonstrated that superionicity might resolve the puzzle. While the immense pressure of all Earth's weight at the inner core combines to keep the iron in a solid matrix, the extreme heat allows lighter atoms to flow and dance around like a fluid – a superionic state that's both solid and liquid.

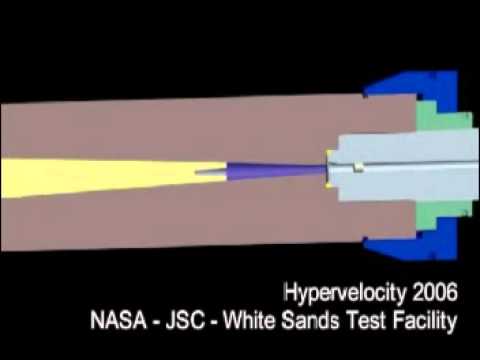

Experimental evidence has just confirmed that possibility. Zhang, He, and their colleagues used a technique called dynamic shock compression to smush a small piece of iron-carbon alloy so hard that it behaved exactly as the same alloy should behave in Earth's inner core.

To accelerate their samples they used two-stage light gas guns – high-precision devices that rely on smokeless gunpowder and compressed gas to send tiny particles flying at extreme speeds.

For this experiment, the iron-carbon projectile was fired at velocities of more than 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) per second at a highly compressible lithium fluoride target. The impact generates a reverse shock that compresses the sample to pressures up to 140 gigapascals and temperatures near 2,600 Kelvin (2,327 °C, or 4,220 °F).

That's not quite as extreme as the inner core, which has a pressure range of 330 to 360 gigapascals and temperatures reaching 5,000 to 6,000 Kelvin, but it's high enough to replicate key aspects of the core environment.

Those simulated conditions last just nanoseconds to microseconds – but that's long enough to probe temperature, density, and acoustic wave propagation using lasers and fast sensors.

And, sure enough, the results matched the low shear-wave velocity and measurement of squishiness – expansion and contraction – known as Poisson's ratio observed in seismic readings of Earth's inner core.

Under these conditions, the researchers showed, the iron matrix stays firmly locked in place, like Batman, while the carbon flows between the gaps like a cavorting Robin.

It's so elegant. It explains why the seismic data looks the way it does and – with experimental data, the closest we'll get to the inner core itself – settles longstanding debates about how light elements behave under extreme pressures.

This may even yield new insights into Earth's magnetic field, a vast structure spun out into space from the dance of conduction and convection deep inside the planet.

"We're moving away from a static, rigid model of the inner core toward a dynamic one," Zhang says. "Understanding this hidden state of matter brings us one step closer to unlocking the secrets of Earth-like planetary interiors."

The research has been published in National Science Review.