Not enough young men are getting vaccinated against the human papillomavirus (HPV), and in some nations, it may be undermining the elimination of cervical cancer.

If more boys receive the Gardasil vaccine, researchers at the University of Maryland in the US think it could save numerous lives from HPV-associated cancers, including cervical, anal, penile, and oral cancers.

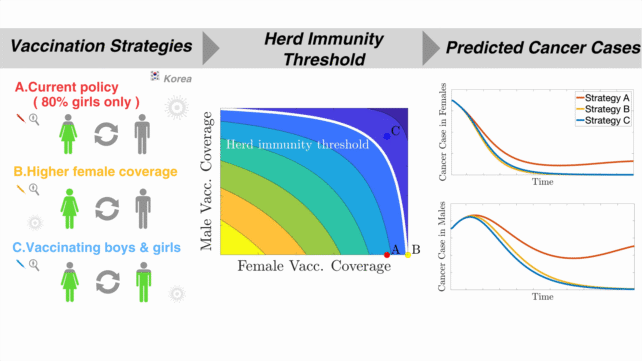

The team's new mathematical model shows that in a nation such as South Korea, where only girls are vaccinated against HPV, current coverage is insufficient to achieve herd immunity against cancer-driving strains.

Related: Young Men Are Dying From Preventable Cancers Because They're Not Getting Vaccinated

Vaccinating 65 percent of boys in the nation could change that.

"Vaccinating boys reduces the pressure of having to vaccinate a large proportion of females," says mathematician and senior author Abba Gumel. "It makes elimination more realistically achievable."

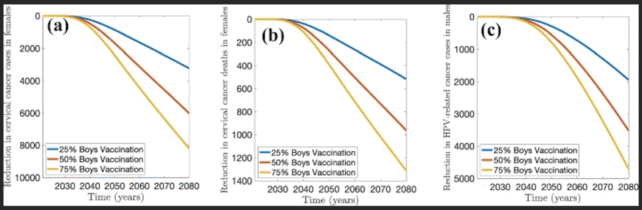

Gumel and his team's simulations suggest that if South Korea's HPV vaccination program were expanded to include boys, the nation could eliminate HPV-related cancers in about 70 years.

The new model was calibrated using cancer data from South Korea, but it could also be used to assess the effectiveness of other national vaccination programs.

Gumel predicts that in a nation such as the US, approximately 70 percent coverage among men and women would be sufficient to achieve herd immunity.

HPV is an exceptionally contagious virus that can be sexually transmitted or transmitted through skin or fluid. It is behind virtually every case of cervical cancer, which kills more than 300,000 people globally each year.

The first HPV vaccine was licensed in 2006, and it was initially rolled out to protect people from dangerous strains of HPV that can lead to cervical cancer.

At first, pharmaceutical companies marketed the vaccination as a preventative medicine specifically for women, and sure enough, the vaccine has proved incredibly effective at preventing cervical cancer. In the past two decades, cervical cancer cases have dropped by almost 90 percent in some regions.

But there are still more lives to save, men included. The persistent 'gender bias' in HPV vaccination policies and public health messaging needs to be addressed for further gains, some researchers argue.

Today, scientists know that both men and women are at risk from HPV-linked cancers, including anal, penile, vaginal, and head and neck cancers. Yet in many nations around the world, far fewer young men are getting their jabs – a massive sex discrepancy that public health advisors want to fix.

In South Korea, for instance, the new model found that the nation is unlikely to eliminate cervical cancer unless more boys get the vaccine.

According to simulations, 99 percent of all young women would need to be immunized under the nation's current vaccination program to achieve herd immunity.

Right now, the percentage of young women vaccinated is at 88 percent, which means HPV and related cancers can still persist in the population.

All that could change, however, if boys got vaccinated, too. If 65 percent of males in the nation were vaccinated, and current female rates hold steady, the new models show that South Korea could reach herd immunity.

If vaccination coverage among females were to drop slightly to 80 percent, the elimination of cervical cancer could still be achieved in South Korea if 80 percent of males were also immunized.

In the past 20 years, South Korea's cases of HPV-related male cancer have tripled. If more boys get vaccinated, it could prevent future deaths from these cancers as well.

In light of these results, the authors of the study argue that young boys aged 12 to 17 should be vaccinated alongside young girls and older women who may have missed the vaccine when they were younger.

Recent evidence suggests that vaccinating older individuals can still provide some protection against this highly transmissible virus.

Related: Young American Deaths From Cervical Cancer Fall Sharply After HPV Vaccine

By some estimates, if the world can achieve widespread HPV vaccination coverage and expand cervical screenings, scientists predict we could eliminate cervical cancer in 149 out of all 181 countries by the turn of the century.

Increasing vaccination rates among boys may be key to achieving those goals.

"We do not have to be losing 350,000 people globally to cervical cancer each year," Gumel says.

"We can see an end to HPV and HPV-related cancers if we improve the vaccination coverage."

The study was published in the Bulletin of Mathematical Biology.