When tissue is severely damaged, surviving cells can respond in a concentrated burst of biological repair known as compensatory proliferation. Nearly 50 years after this survival strategy was first identified in fly larvae, scientists have now pinpointed the molecular mechanism behind it.

Understanding how this process works – and how it might be manipulated – could help develop new ways to stop cancer from returning, according to the researchers, led by a team from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Crucial to the discovery are caspases, enzymes linked to programmed cell death (where the body destroys cells to stay healthy or sculpt tissues). In recent years, studies have shown that caspases aren't always killers – they are involved in a variety of other essential processes, which led to their study here.

Related: The Stem Cell Secrets of This Tiny Worm Could Help Unlock Human Regeneration

The research team went back to the beginning with compensatory proliferation, using the same experiment that led to its discovery: blasting fruit-fly (Drosophila melanogaster) larvae with high-dose radiation. This time, the scientists were looking much more closely at the regeneration stage.

"We set out to identify cells that push the self-destruct button but survive anyway," says first author and molecular geneticist Tslil Braun, from the Weizmann Institute.

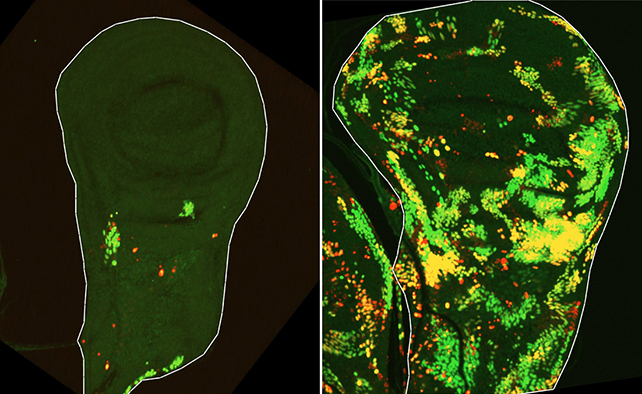

"To do this, we used a delayed sensor that reported on cells in which the initiator caspase had been activated but that nevertheless survived the irradiation."

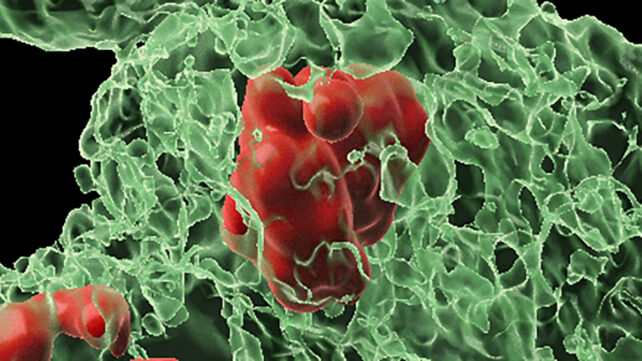

The researchers discovered that, following radiation damage, tissue regenerates through teamwork between two types of surviving cells.

Cells of one type are initially marked for death – they activate a fruit fly caspase called Dronc – but ultimately they resist dying and rapidly multiply themselves to repair damaged tissue. The team named them Dronc-activating (DARE) cells.

Further analysis revealed that DARE cells don't act alone.

"We identified another population of death-resistant cells, but unlike DARE cells, they showed no activation of the initiator caspase. We called them NARE cells," Braun says.

Although these NARE cells weren't labeled for death, they're recruited by the DARE cells to perform repairs. They also regulate the process to prevent too much regeneration.

Importantly, the survivor DARE cells and the repaired tissue they help generate are even more resistant to death. After a second blast of radiation, they became far harder to kill, a phenomenon that's previously been seen in cancer tumors.

"The descendants of DARE cells were found to be exceptionally resistant – seven times more resistant to cell death than cells in the original tissue," says molecular geneticist Eli Arama, from the Weizmann Institute.

"This may help explain why recurrent tumors become more resistant after radiation."

The researchers also identified a molecular motor protein, Myo1D, that appears to protect DARE cells from death. Again, there's a link to cancer biology: it's thought that cancers can also harness Myo1D to stay alive.

While these results still need to be confirmed in human tissues, now that we know the detailed mechanics of compensatory proliferation, it's far more likely that scientists will find ways to boost or enable it (healing tissue damage) or block it (stopping cancer).

"We hope that, as has often been the case with fly models, the knowledge gained here can be translated into an understanding of the mechanisms that balance growth and confer resistance to cell death in human tissues," says Arama.

"The results also point toward new ways in which we might be able to accelerate beneficial regeneration of healthy tissue after injury."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.