The first material ever collected from the far side of the Moon could help settle a long-held lunar mystery.

According to a Chinese Academy of Sciences analysis of Moon dust ferried to Earth by China's Chang'e-6 mission, the reason the natural satellite's two hemispheres are so different may be due to a giant impact long ago that literally altered the Moon's composition from the inside out.

It's a conclusion that neatly connects several features of the lunar far side, and shows that meteorite impacts aren't just cosmetic scars on a planet's surface – they can dramatically and permanently reshape the interiors of worlds.

Related: China Brought Something Unexpected Back From The Far Side of The Moon

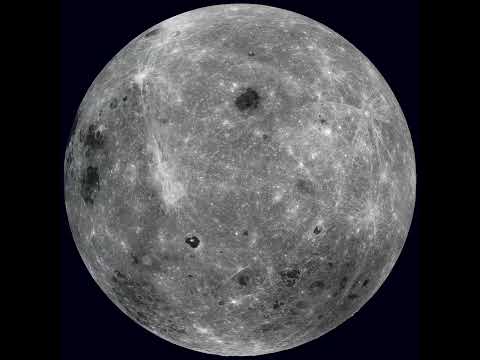

The asymmetry of the two hemispheres of the Moon has puzzled scientists since the Soviet probe Luna 3 took the first pictures of the far side in 1959. Even in the grainy images obtained, the difference was clear. While the side of the Moon that faces Earth looks piebald, marked by vast, smooth, dark basalt plains, the far side is lighter-hued and heavily crater-scarred.

Many possible reasons for this have been investigated, including a link to the largest known impact crater in the Solar System – the South Pole-Aitken Basin, which takes up nearly a full quarter of the lunar surface.

However, without physical access to lunar samples, confirming this connection has been difficult.

The China National Space Administration's Chang'e-6 mission is a game-changer. It's the first – and so far only – mission to have ever delivered far side Moon dust into the hands of Earth scientists in a magnificent feat of human ingenuity. Since the capsule containing the dust landed in 2024, scientists have been working to uncover its secrets.

In the new work, a team led by planetary scientist Heng-Ci Tian analyzed the potassium and iron in the sample, which was collected from the South Pole-Aitken Basin.

The team was looking for differences between the isotopes in samples from the far side and samples obtained from the lunar near side during the Apollo program and China's Chang'e-5 mission. Isotopes are versions of the same element with different numbers of neutrons, which changes their atomic mass while leaving their chemical behavior the same.

The researchers compared the basalt samples' isotopes against previously published isotope values and compared them against previously published isotope values for Apollo basalts and Chang'e-5 basalts.

The results showed a clear difference between the two hemispheres. The Apollo and Chang'e-5 basalts had a higher proportion of lighter isotopes of iron and potassium, compared to the heavier isotopes they found on the far side. This difference cannot be explained by volcanism, since it doesn't alter the potassium isotopes in the way the researchers observed.

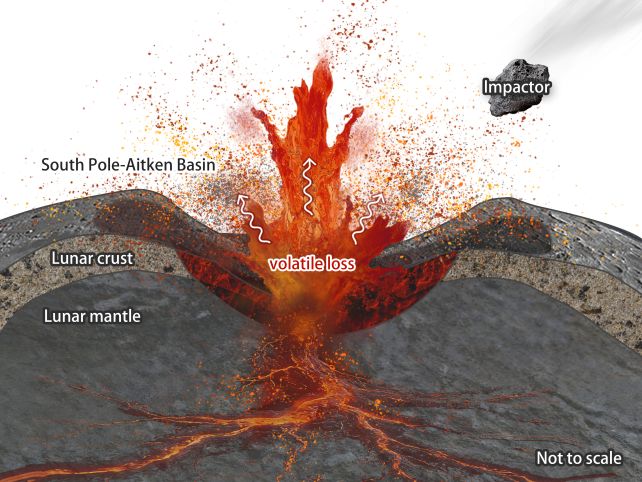

This suggests that when the South Pole-Aitken impactor hit, it gouged deep into the Moon, generating intense heat. This melting would have vaporized material in the lunar mantle, with a preference for lighter isotopes that evaporate more readily.

"Although magmatic processes can explain the iron isotopic data, the potassium isotopes necessitate a mantle source with a heavier potassium isotopic composition on the farside than on the nearside," the researchers write.

"This feature most likely resulted from potassium evaporation caused by the South Pole-Aitken basin-forming impact, demonstrating the profound influence of this event on the Moon's deep interior. This finding also implies that large-scale impacts are key drivers in shaping mantle and crustal compositions."

Because the impact punched deep into the Moon's mantle, it would have altered potassium isotopes to significant lunar depths. It's a mechanism that neatly explains the observed isotope differences between the sample sets, and gives scientists a new tool for interpreting lunar data.

It may have even induced hemisphere-scale mantle convection, although further samples from other regions of the far side of the Moon will be needed to tell us that.

We already know that the Moon's biggest impact changed it forever. This new research suggests those lasting scars extend far deeper than the surface, altering the Moon's chemistry in ways that cannot be erased by time.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.