It looks like NASA's Mars Sample Return mission has come to a bureaucratic end.

The mission was to be the crowning achievement in the study of Mars and all the questions surrounding its ancient habitability. But the US Congress has drastically cut the mission's funding, effectively canceling the mission as it was intended.

Despite decades of study and technological improvement and innovation, the issue of Martian habitability has been difficult to solve. Mars surface landers Curiosity and Perseverance have widened and deepened our understanding of the planet, and have provided tantalizing evidence for warm, wet periods on Mars conducive to life.

Related: WATCH: NASA Conducts First-Ever Medical Evacuation From The ISS

But the next step was to return Martian rock samples to Earth, where the investigative power of modern labs could be brought to bear on them.

As far back as 2011, returning samples from Mars was recognized as a high priority in NASA's planetary science endeavours.

Even today, NASA's webpage for MSR states that "Mars Sample Return (MSR) would be NASA's and ESA's (European Space Agency) ambitious, multi-mission campaign to bring carefully selected samples to Earth.

"MSR would fulfill one of the highest-priority Solar System exploration goals from the science community. Returned samples would revolutionize our understanding of Mars, our Solar System, and prepare for human explorers to the Red Planet."

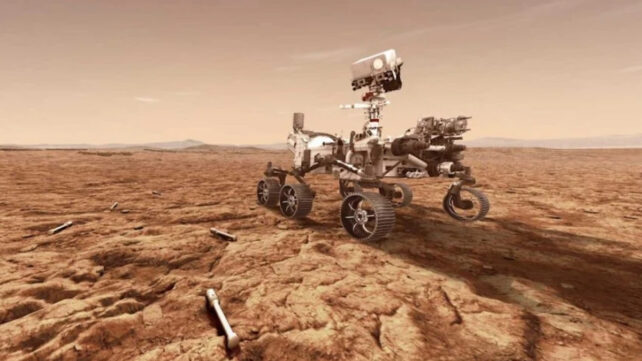

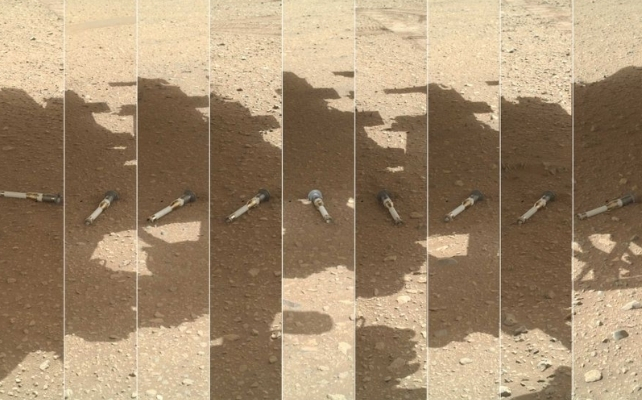

The Perseverance rover was the first stage of the mission, and it has performed exceptionally well. The rover has gathered and cached 33 sample tubes of interesting rocks and dust, ready for retrieval by the MSR.

Now, the fate of those samples is unclear.

NASA knew that they were in tough territory. The estimated cost to retrieve the samples ballooned to 11 billion dollars. After working on new mission architectures, they were able to get the estimated cost down to about 7 billion dollars.

But those were just estimates, and because it's such an unprecedented mission, there was a clear lack of certainty around those numbers.

The issue is money. There's heavy pressure on NASA to reduce its budget. Since the MSR still required large amounts of money, and since the technology to achieve it still wasn't clear, it was the obvious choice for cancellation.

The mission was extremely complex. The current design involved sending a lander to the surface. Perseverance would deliver the sample tubes to the lander, and if that were not possible, a pair of small sample return helicopters would do the job.

The lander also had a rocket that would carry the samples to Martian orbit. From there, it would rendezvous with an orbiting spacecraft that would send the samples back to Earth. To say this was a complex undertaking is an understatement.

The budget still provides some money for developing technology related to further exploration of Mars, but only a small amount.

Some of that money may lead to new technologies and a more budget-friendly way of retrieving the cached samples. But that is far from certain.

It's also possible that technology will be developed that can study the samples effectively on the surface, and returning them to Earth won't be necessary. But the technology in Earthly labs will advance at the same rate. It's difficult to conceive how studying them on Mars will ever be as effective as studying them on Earth.

Related: Life on Mars? NASA's Stunning Discovery Is The Best Evidence Yet

The future is always unwritten and unknown. Maybe the MSR will be revived at some point in the future. Maybe the ESA will go it alone. China has plans for a Mars sample return mission, and now the path is clear for them to be the first to return Martian samples to Earth.

However, their mission is not as sophisticated as the NASA/ESA mission. While Perseverance's samples are carefully chosen for maximum science benefit, China's mission is more of a grab-and-go endeavour.

Fortunately, the sample tubes are likely to sit there waiting for a long time, unlikely to be degraded in Mars' cold, dry environment.

But for scientists who have put their hearts and minds into this ambitious mission, the news must be crushing.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.