The je ne sais quoi that gives Black Ivory coffee its smooth, chocolatey flavor may lurk deep in the bowels of Earth's largest land animals.

According to a new examination of the microbes that live in the guts of Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), researchers have found certain groups of bacteria that are likely breaking down compounds that otherwise make coffee bitter.

"Our previous study revealed that Gluconobacter was the dominant genus in the gut of civet cats, and it may produce volatile compounds from the coffee beans, suggesting that microbial metabolism contributes to the coffee aroma," says genomicist Takuji Yamada of the Institute of Science Tokyo in Japan.

"These findings raised the question of whether the gut microbiome of elephants similarly influences the flavor of Black Ivory coffee."

Related: 'World's Most Expensive Coffee' Is Chemically Different Because It's Literally Poop

Black Ivory coffee is among the most expensive coffees in the world, leaving kopi luwak – coffee digested by civets (not actually cats) – in the dust.

It's made only at one elephant sanctuary in Thailand, where some elephants are fed unprocessed coffee cherries. Sanctuary workers later collect the digested coffee beans from the elephants' poop, then clean and roast them for human consumption.

The coffee is renowned for its flavor, which is often described as superior.

Yamada and his colleagues, after discovering that the gut bacteria of civets may play a role in the flavor of kopi luwak, wanted to know if a similar mechanism was helping shape the flavor profile of Black Ivory coffee.

They performed their study not by analyzing the coffee beans, but by looking directly at elephant poop to take a census of gut microbes. They took samples from six elephants in the sanctuary – three that had eaten coffee cherries, and three that had not, which served as a control group.

The only difference in their diets was a snack fed to the coffee elephants consisting of bananas, coffee cherries, and rice bran. So if there was anything different about their gut microbiome, it was most likely because of this additional snack.

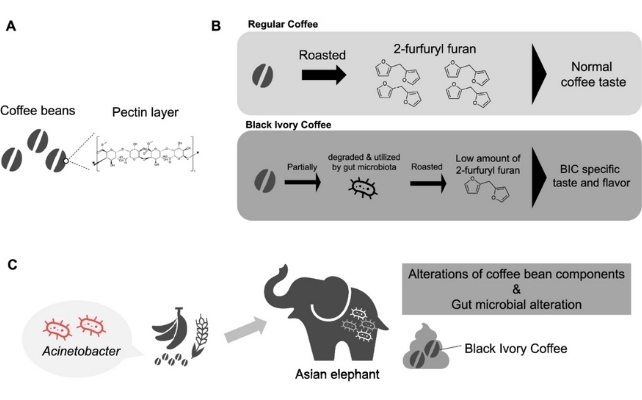

The bitterness of coffee comes, in part, from a compound called pectin that is found in plant cell walls, as well as cellulose. During the roasting process, pectin and cellulose break down into bitter-tasting compounds.

Sequencing the poop samples, the researchers found coffee-digesting elephants had a much higher proportion of gut microbes that are involved in breaking down pectin and cellulose. Some of the bacterial species were not found in the control group at all.

Using previously published data, the researchers also compared the microbiomes of the coffee elephants to those of cattle, pigs, and chickens, to see if they could find any other potential coffee digesters.

While some of the relevant bacterial species could be found, only the elephants' guts had the full toolkit required for breaking down pectins and cellulose.

A 2018 study found that Black Ivory coffee has much less of a compound called 2-furfuryl furan than regular coffee beans. That's one of the bitter compounds produced by pectin breakdown during the roasting process.

The new analysis of elephant microbiomes suggests that the partial digestion of the coffee cherries helps strip away the parts of the coffee beans that turn bitter during roasting, resulting in a much more delicious flavor profile.

The next step would be to study the beans themselves.

"Our findings may highlight a potential molecular mechanism by which the gut microbiota of Black Ivory coffee elephants contributes to the flavor of Black Ivory coffee," Yamada says.

"Further experimental validation is required to test this hypothesis, such as a biochemical analysis of coffee bean components before and after passage through the elephant's digestive tract."

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.