Every critter on this planet that relies on a sexual means of reproduction has its own way of luring in a mate – but cuttlefish can do something really special.

Male Andrea cuttlefish (Doratosepion andreanum) – quite drab to human eyes – use their birefringent arms to literally twist light, creating a highly conspicuous signal precisely tuned to cuttlefish vision.

We already knew that the extremely weird eyes of cuttlefish can see the orientation of waves of light, or polarization. This new discovery shows that they take it a step further, actively manipulating polarization to communicate in specific ways.

Related: A Cephalopod Has Passed a Cognitive Test Designed For Human Children

"Our findings," writes a team led by aquatic bioscientist Arata Nakayama of the University of Tokyo, "show the significant contribution of polarization of light to animal communication and reveal that polarization signals – like colorful sexual ornaments – can achieve high conspicuousness through fundamentally different optical mechanisms."

The cuttlefish communication toolkit is fascinatingly complex, involving both mesmerizing color and pattern changes, and performing elaborate gestures with their flexible arms.

They also have strange eyes, unlike those of any other animal, with unique W-shaped pupils. Although they are thought to be colorblind, they can see properties of visible light beyond the ability of humans – the polarization of its transverse waves.

When light travels, it usually vibrates in many directions at once, but its motion can also be restricted to a single orientation – a property known as polarization. Polarized sunglasses work by blocking light vibrating in certain directions, allowing only light oriented a specific way to pass through the lenses.

Bouncing off certain surfaces or traveling through a translucent or transparent medium can also force those vibrations into a preferred direction, thereby polarizing light.

Ever since they learned that cuttlefish can see polarization, scientists have suspected that this feature of light might form part of their communication toolkit. A 2004 study not only discovered that cuttlefish body tissues polarize light – it also found limited evidence that the animals respond to that signal.

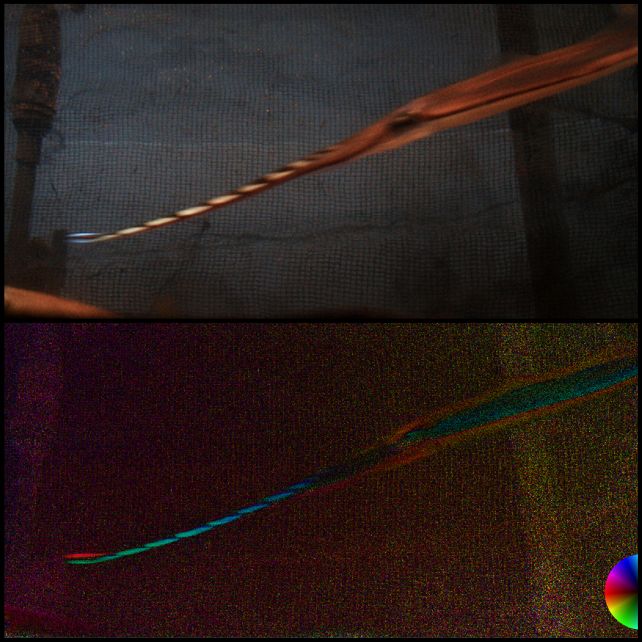

Nakayama and his colleagues designed a more rigorous study to find out, filming the courtship arm gestures of male Andrea cuttlefish.

These cephalopods have two extra-long, sexually dimorphic arms that, when wooing a mate, they coil and extend straight out in front, while iridescent bands of color are displayed on their bodies.

The researchers collected wild cuttlefish and put male-female pairs in observation tanks with carefully controlled lighting conditions to reproduce the horizontal polarization of light in the ocean. They also filmed each encounter with polarization cameras, as well as taking footage of the cuttlefish in a non-courting state as a baseline.

The videos showed that, when the cuttlefish twists these arms in a certain way, horizontally polarized light passes through the translucent muscle. This tissue is also birefringent, rotating the light's polarization by nearly 90 degrees to a vertical position.

The process produces alternating bands of horizontally and vertically polarized light – maximum contrast for cuttlefish vision, a signal that is uniquely tuned for attention. It's like a bold serenade, but in light.

What's fascinating about this is that the cylindrical shape of the arm dials up this contrast, the perfect shape to convert a horizontal beam of light into a vertical one.

In a baseline state, the cuttlefish did not produce a polarization signal. This suggests that these animals evolved a perfect biological waveplate just to help them make babies.

Whether cuttlefish use polarization signals beyond courtship remains an open question – one that may only be answered once scientists learn how to see more of their hidden visual world.

"Just as with the long-recognized and extensively studied diverse selection of animal coloration, there may be a similar diversity of polarization signals among polarization-sensitive animals – signals that remain entirely unknown to us because they are invisible to the human eye," the researchers write.

"This study sheds light on a part of that hidden diversity."

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.