Rows of preserved specimen jars from Charles Darwin's iconic Galapagos voyage have sat, unopened, in the archives of London's Natural History Museum (NHM) for 200 years. Now, lasers have given us an unprecedented look inside.

Darwin himself is known for penning the now widely-accepted theory of natural selection and evolution, founded in part upon his observations of wildlife in the Galapagos while he was aboard the HMS Beagle.

Scientists have learnt plenty from his preserved specimens – the mammals, reptiles, fish, and shrimps, to name a few – which can be seen through the glass that entraps them.

But until now, there has been no way of knowing what kind of liquids these priceless specimens are floating in without cracking them open.

"Analyzing the storage conditions of precious specimens, and understanding the fluid in which they are kept, could have huge implications for how we care for collections and preserve them for future research for years to come," explains NHM research technician Wren Montgomery.

"Until now, understanding what preservation fluid is in each jar meant opening them, which risks evaporation, contamination, and exposing specimens to environmental damage," says physicist Sara Mosca from the Central Laser Facility at the United Kingdom's Science and Technology Facilities Council.

A lot of different fluids have been used in specimen preservation throughout history. Usually, alcohols like ethanol and methanol are involved, but in the late 19th century, the newly-discovered formaldehyde became popular.

Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch steeped aromatic spices (clove, pepper, and cardamom) in an ethanol–water base. French histologist Pol Bouin favored a recipe of formaldehyde, picric acid, and acetic acid. And German pathologist Carl Kaiserling's method involves dipping specimens sequentially in formaldehyde, potassium nitrate, and glycerin.

"Over time, the variability in recipes… has led to considerable heterogeneity across collections, with mixtures of ethanol, methanol, glycerol, and formaldehyde commonly encountered in unknown proportions, further altered by potential evaporation and contamination over time," Montgomery, Mosca, and their colleagues explain in a published paper summarizing their findings.

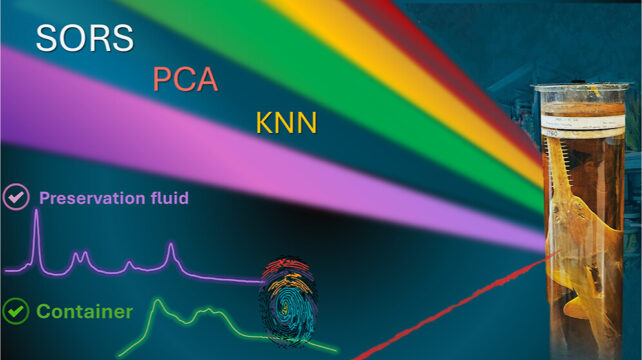

To probe the jars' insides without endangering them, Montgomery, Mosca, and a team of scientists have turned to a portable form of laser spectroscopy called spatially offset Raman spectroscopy, or SORS.

Raman spectroscopy measures the level of 'excitement' in a material's molecular structure following a hit from a laser. Light that is reemitted by the molecules returns a spectral fingerprint of the elements within, revealing the material's chemical makeup.

But traditional, single-laser Raman spectroscopy wouldn't work for jars like this. Light from the laser is scattered within the first few hundred micrometers, which means the container's surface dominates the signal.

SORS overcomes this by taking at least two Raman measurements: one at the source, and one that's a little further away and offset. Subtracting these two readings reveals the chemical signatures of both the surface and subsurface. And for even more complex materials, scientists will take multiple readings, using multiple lasers offset to different degrees from the main source.

Applying the method to Darwin's jars allowed the researchers to accurately identify their preservation fluids in nearly 80 percent of the jars. Another 15 percent of cases were partially accurate, and only three samples (6.5 percent) were unable to be confidently identified.

The study revealed that the mammals and reptiles were most often 'fixed' with formalin and then suspended in ethanol. Meanwhile, invertebrates (especially the jellyfish and shrimp) were stored in formaldehyde or buffered formaldehyde, sometimes with a bit of glycerol or phenoxetol sprinkled in to improve tissue integrity.

Related: Darwin's Headache: Evolution's Clock Might Tick at Different Speeds

It's an important question for those tasked with looking after Darwin's haul, but this doesn't just affect the HMS Beagle collection: museums around the world house over 100 million fluid-preserved specimens, many of which are too risky to open.

"This technique allows us to monitor and care for these invaluable specimens without compromising their integrity," Mosca says.

The research was published in ACS Omega.