Cancer is transported from one organ to another by invisible bubbles. Understanding these microscopic messengers could change the fight against metastasis.

Preventing cancer from spreading throughout the body is the goal of our team at the Department of Electrical Engineering at the École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS).

In collaboration with Prof. Julia Burnier and biology specialists at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, we are working to understand how cancers transform into metastases; in other words, how they invade other organs.

Related: A Hidden Warning Sign Discovered in The Gut May Increase Cancer Risk

For about eight years, my team has been studying lipid nanoparticles, which are barely 100 nanometers in size and invisible to the naked eye. Our first task is to understand the path of metastasis. Then we try to determine different ways to inject drugs into the body.

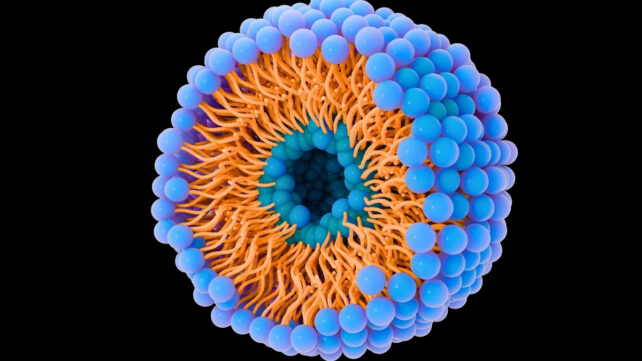

Lipid nanoparticles, such as liposomes, differ from conventional approaches to cancer treatment because they deliver drugs directly to tumour cells. That increases their effectiveness and reduces toxicity compared to conventional chemotherapy.

Researchers have demonstrated that liposomes target tumours more effectively and reduce side effects, while others have observed that these nanomedicines improve the penetration and specificity of treatment, particularly in the case of metastases.

These results confirm that nanomedicines can make cancer treatments more targeted, more effective, and improve their tolerability.

Lipid nanoparticles deliver drugs directly to tumour cells. (Tumeggy/Science Photo Library/Getty Images)

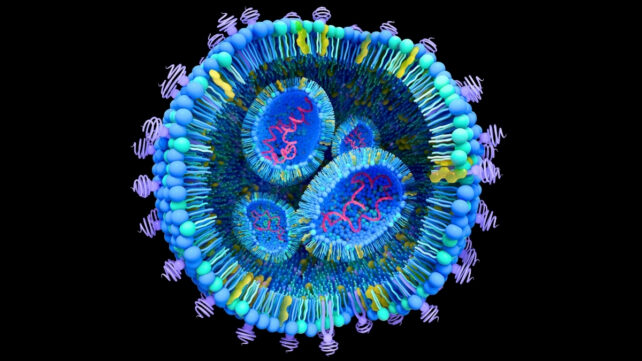

Lipid nanoparticles deliver drugs directly to tumour cells. (Tumeggy/Science Photo Library/Getty Images)

Tiny particles responsible for spreading

Every cell in our body, whether healthy or cancerous, releases tiny particles called extracellular vesicles. These small bubbles, made of lipids and proteins, also carry genetic information.

When a cancer cell releases its vesicles into the bloodstream and they are transferred to a healthy cell, they can alter its DNA and turn it into a cancer cell. This is how cancer spreads to other organs, such as the liver. This mechanism is the basis of metastasis.

The problem is, extracting and studying these natural vesicles is a long and difficult process. To speed up our research, my team produces artificial copies called liposomes using small devices called micromixers.

By mixing different solutions – lipids, proteins, water, and ethanol – our research team creates particles that resemble natural vesicles. The challenge is then to understand which lipids and proteins are contained in extracellular vesicles in order to produce liposomes.

We then inject these liposomes into liver cancer cells to see how they react. The more the cells retain these particles, the more it proves that the copies mimic reality well.

In a typical experiment, liposomes are manufactured with precise parameters to reproduce the size and charge of extracellular vesicles. They are also made visible by staining them with a fluorescent marker.

These liposomes are then incubated with cancer cells grown in our laboratory. This makes it possible to film and measure, in real time and without disturbing the cells, how and at what speed the liposomes are absorbed and expressed by the cancer cells.

Our results show that the more the liposomes resemble natural vesicles in size and charge, the more effectively they are absorbed. This allows us to see how their chemical and physical composition influences how they are absorbed by cells and their possible role in tumour development.

Observing the behaviour of liposomes

Our goal is to understand how these extracellular vesicles are transported to liver cells to create metastases. The main challenge is to ensure that these liposomes can truly mimic extracellular vesicles.

We are currently achieving a 50 per cent efficiency rate for protein encapsulation. We aim to increase this to 90 per cent. We hope this will enable us to explain how metastases form so that we can block them. Once the technique has been refined, our team will conduct tests on rats.

In the long term, this work could be a game-changer for many patients by preventing the formation of metastases and increasing their chances of survival. Our goal: to understand and block metastases.

Towards new treatments

Our team seeks not only to understand the process, but to develop new weapons against cancer. The idea is to use these liposomes as tiny shuttles that can transport drugs directly to cancer cells.

The diameters of the liposomes differ depending on the cancerous organ to be treated. Therefore, it's very important to properly characterize and understand the properties of these liposomes.

For example, researchers are currently testing the encapsulation of turmeric, which has been studied for its anti-cancer properties. Our team is doing the same to observe how cancer cells react to these liposomes.

It's thought that turmeric, and more specifically the curcumin it contains, helps fight cancer by slowing the growth of tumour cells and promoting their destruction by the body.

Many studies have confirmed its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, which can enhance the action of cancer treatments. By encapsulating turmeric in liposomes, we are improving its ability to reach and target diseased cells.

Unlocking the secret of cancer spread

In addition to this molecule, other molecules such as paclitaxel are already used in cancer treatments in liposomal form. Encapsulated paclitaxel improves drug delivery and tolerance.

There are also innovative strategies that use liposomes to transport small pieces of DNA or antibodies that act as messengers, which help the body to better detect and fight diseased cells.

These approaches have been validated in several scientific studies and are already being used in certain cancer treatments, with new advances being made every year to improve their effectiveness and safety.

Related: Scientists '3D Print' Material Deep Inside The Body Using Ultrasound

By using liposomes to replicate the body's natural vesicles emanating from cancer cells, our team hopes to unlock the secret of how cancer spreads and determine effective approaches to block it. Our research paves the way for more targeted treatments that can prevent metastasis and improve patient survival rates.![]()

Vahé Nerguizian, Professeur titulaire, École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.