A parasite that lives permanently in the brains of millions may not be as uniformly dormant as scientists once thought.

Researchers at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) have recently found evidence of low-level T. gondii reactivation in the brains of mice, even during long-term infection.

Today, more than a third of the world's human population is infected by Toxoplasma gondii, a brain-invading parasite that reproduces in cats with mice and other animals acting as intermediate hosts.

Though the pathogen often ends up in a healthy human, following contact with cat feces or raw meat, infections typically cause no symptoms, meaning few are any the wiser.

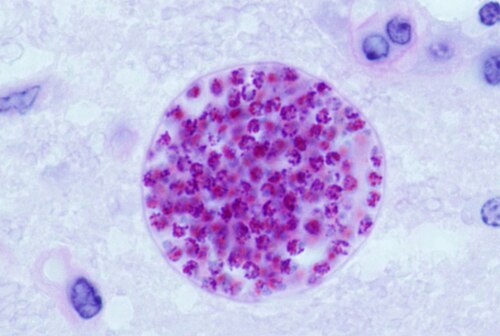

Unbeknownst to its host, the parasite creates cysts within the tissues of the human brain, heart, and muscle, where it can then reside for a lifetime – seemingly inactive until immune defenses falter.

But something seems to be going on inside these cysts.

Related: Cat Parasite Can Seriously Disrupt Brain Function, Study Suggests

Until now, it was assumed that each tiny cyst contains but one single type of T. gondii that lies dormant. But researchers at UCR have used single-cell RNA sequencing to reveal several subtypes all hunkering down together in the brains of their test animals.

In mice, at least, the parasite seems to cluster in up to five distinct forms. These various forms of T. gondii develop and grow in different ways and at different rates. After a few days of growth in the lab, some subtypes can even approach stages associated with renewed activity.

"We found the cyst is not just a quiet hiding place – it's an active hub with different parasite types geared toward survival, spread, or reactivation," explains biomedical researcher Emma Wilson from UCR.

"Our work changes how we think about the Toxoplasma cyst," she adds. "It reframes the cyst as the central control point of the parasite's life cycle. It shows us where to aim new treatments. If we want to really treat toxoplasmosis, the cyst is the place to focus."

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by T. gondii in humans that can cause a flu-like illness with psychiatric symptoms. It typically occurs in those with weakened immune systems, sometimes triggering seizures or vision issues.

Antiparasitic treatment can help, but addressing the active disease and the dormant form requires different medicines.

"By identifying different parasite subtypes inside cysts, our study pinpoints which ones are most likely to reactivate and cause damage," says Wilson.

"This helps explain why past drug development efforts have struggled and suggests new, more precise targets for future therapies."

In the brains of mice chronically infected (for 28 days) with T. gondii, Wilson and colleagues found that cysts contained a greater diversity of parasite subtypes than in the acute stage.

In the first week or so of infection, the parasites seemed to switch to a faster-growing stage, but afterward they shifted to a slower-growing phase and forms that maintained the cysts.

A linear, stepwise form of maturation, the authors say, is unlikely, and that means our understanding of this parasitic infection needs updating.

"For decades, the Toxoplasma life cycle was understood in overly simplistic terms," says Wilson. "Our research challenges that model."

The study was published in Nature Communications.