Mars's water disappeared somewhere, but scientists have been disagreeing for years about where exactly it went.

Data from rovers like Perseverance and Curiosity, along with orbiting satellites such as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and ExoMars, have shown that Mars used to be a wet world with an active hydrodynamic cycle.

Obviously, it isn't anymore, but where did all the water go?

A new paper that collects data from at least six different instruments on three different spacecraft provides some additional insight into that question – by showing that dust storms push water into the Red Planet's atmosphere, where it is actively destroyed, all year round.

Experts think that, at one time, Mars had enough water on its surface to cover most of that surface to a depth of hundreds of meters. To estimate this, they use a technique called the deuterium/hydrogen (D/H) ratio.

Deuterium, a heavier isotope of hydrogen, makes up a small percentage of hydrogen atoms in all water molecules. This slightly heavy version of water – known colloquially as "heavy water" – is less likely to be pushed high into the atmosphere, where it is subsequently destroyed by UV radiation, and the resulting hydrogen atoms are blown away by the solar wind.

Therefore, over time, the ratio of deuterium to regular hydrogen in water increases, as more and more of the lighter form of the element is blown away.

Scientists have measured this D/H ratio on Mars as being 5-8 times that of Earth's. Extrapolating out those calculations, that would have meant there was enough water on Mars to cover most of its surface to a depth of a few hundred meters, possibly in the form of ice.

Finding an answer to where that water went requires an understanding of Mars's seasons.

The Red Planet has an axial tilt, like Earth, which means it also has seasons. However, it also has a much more pronounced elliptical orbit, meaning that one 'summer', where the planet is nearer its perihelion (its closest point to the Sun), is much warmer than the other, when it is nearing aphelion – the farthest point from the Sun.

For Mars, that means southern summers are much warmer than northern ones, and scientists have long believed that the process by which water made its way into the atmosphere only happened during the relatively warm periods of southern summers.

However, this new paper throws a wrench in that assumption by showing the process of water loss due to a very specific kind of 'rocket storm' in the northern hemisphere a few years ago.

Warmer summers increase moisture loss due to the process by which water is injected into the upper atmosphere, where it is less protected from the UV radiation that breaks it into its constituent molecules.

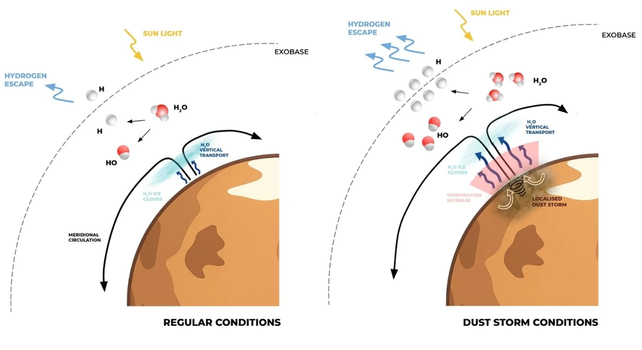

During the southern summer's dust storms, dust is forced into the middle layers of the atmosphere, where it warms the air by approximately 15°C. Typically, water ice clouds would form at around that height, trapping the water by freezing its molecules together.

With the increased warmth from the dust, those ice clouds no longer form, allowing water to be pushed higher into the upper atmosphere by storms, where it is subsequently destroyed by radiation.

Scientists had previously thought this only happened during southern summers. Still, data from ExoMars, the Emirates Mars Mission (EMM), and the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter captured a strong storm during the northern summer back in Mars year 37 (2022-2023 for Earth), the likes of which had never been seen before.

Clearly, they caused the same water destruction process as was expected during southern summers. It proved that cycles of dust storms threw water into the upper atmosphere year-round, suggesting its destruction wasn't limited to specific periods of Mars' history.

Related: Mars: Scientists Have Figured Out How Blue The Red Planet Used to Be

Admittedly, that rocket storm seemed exceptionally strong, but the researchers think that in Mars's past, its axial tilt might have been even more tilted towards the Sun, which would have encouraged this type of storm formation in what would have been much warmer northern summers.

This extra 'escape pathway' for water could explain some of the discrepancy between the amount of water Mars currently has, the amount we believe it used to have, and the processes we think might have destroyed it.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.