The last common ancestor of all living things did not just suddenly appear on Earth roughly 4.2 billion years ago.

Some of its genes came from an even older and more mysterious source…

"While the last universal common ancestor is the most ancient organism we can study with evolutionary methods," explains biologist Aaron Goldman from Oberlin College in the US, "some of the genes in its genome were much older."

These super-old protein-coding genes are worth considering further if we want to learn more about the foundations of life on Earth, argue Goldman and two other biologists in the US, MIT's Greg Fournier and University of Wisconsin-Madison's Betül Kaçar, in a new perspective.

They aren't the first to use ancient gene families to infer the deepest parts of evolutionary history, but the trio wants to underline the point now that key advances in ancestral sequence reconstructions have allowed for closer inspection of the last universal common ancestor's (LUCA's) genome than ever before.

Genetics, like history, is written by the victors. If a living being did not leave behind descendants, then we have little way of knowing they ever existed.

The fossil record simply doesn't extend as far back as the LUCA's likely lifetime, which leaves our genes as one of the only real-world clues.

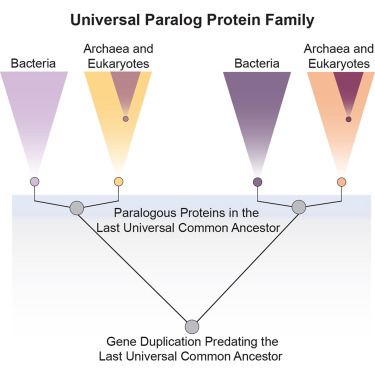

Anciently duplicated gene families, otherwise known as 'universal paralogs', are rare double-ups found in every branch of life on Earth today. This means they must have doubled up before those branches split apart.

If LUCA is the trunk of our genetic family tree, then earlier single-celled organisms that presumably harbored these duplicate genes were the roots of life itself – the long-buried precursors that helped give rise to animals, plants, fungi, and bacteria.

"By following universal paralogs," says Kaçar, "we can connect the earliest steps of life on Earth to the tools of modern science. They provide us a chance to transform the deepest unknowns of evolution and biology into discoveries we can actually test."

Scientists can only hypothesize about what was going on when LUCA lived, let alone what came before. It is likely that LUCA did not roam Earth alone but rather coexisted within an "established ecological system" that would have been "modestly productive".

How simple or complex these organisms or their ecosystems were remains up for debate.

Only a few universal paralog protein families are currently known, write Goldman and colleagues, but this paucity "is not necessarily due to a lack of paralogs in the actual proteome of the LUCA."

Over time, many paralogs in the LUCA proteome were likely lost from the family tree due to evolutionary events, genetic divergence, or horizontal gene transfer (a common way bacteria share genes across a population).

This could obscure the ancient nature of some protein-specific genes still at work today.

"For these reasons, it is likely that most protein families that were present in the LUCA may not be detectable through phylogenetic analyses," the authors write.

That is limiting, however, it makes whatever can be studied that much more special.

"The history of these universal paralogs is the only information we will ever have about these earliest cellular lineages, and so we need to carefully extract as much knowledge as we can from them," says Fournier.

Related: Scientists Reveal How They Identified The Ancestor of All Life on Earth

Some universal paralogs, for instance, are involved in the genetic translation system, which the authors of the perspective argue "is likely the most ancient molecular system retained in extant life today."

Other universal paralogs are related to enzyme production or proteins involved in maintaining the function of biological membranes.

Recently, for instance, a line of research has revealed that there are pre-LUCA ancestors of enzymes known as aminoacyl tRNA synthetases.

To say these enzymes are important to life is an understatement. They are responsible for tying the right amino acid to its matching transfer RNA, which moves those amino acids into a sequence that forms a protein.

The fact that their ancestors existed pre-LUCA suggests that early life forms could incorporate amino acids into genetically encoded proteins even before their more modern relatives evolved.

"Taken together, these results support that the transition to a modern genetic code before the LUCA was a complex evolutionary process incorporating multiple mechanisms, including co-evolution with amino acid biosynthesis pathways," the authors conclude.

The study was published in Cell Genomics.