Researchers have found compelling evidence that depression points to the development of Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia later in life, with depressive symptoms often appearing several years before signs of a neurological condition.

A team from Aarhus University in Denmark studied health records to see if these neurological conditions had a unique relationship to depression.

Clinician-scientist Christopher Rhode and his colleagues compared Parkinson's and Lewy body dementia to three other chronic illnesses that can seriously affect daily life: rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease, and osteoporosis.

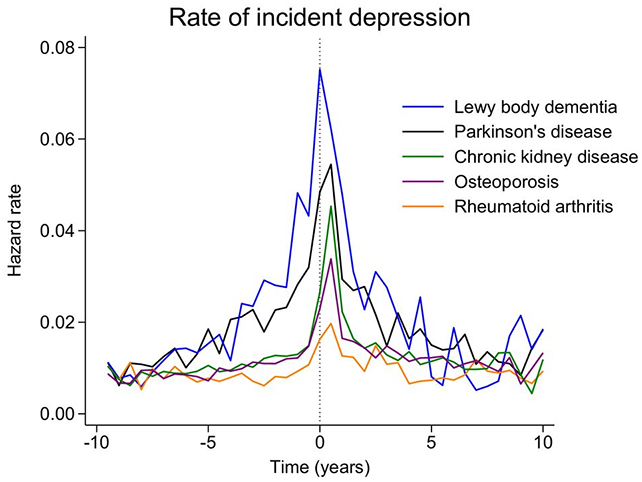

The researchers found a significantly higher risk of depression in individuals with Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia compared to those with the other conditions.

What's more, depression rates began climbing around eight years before a formal diagnosis of either, and they stayed elevated for at least five years after diagnosis.

"Following a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia, the persistent higher incidence of depression highlights the need for heightened clinical awareness and systematic screening for depressive symptoms in these patients," the authors write in their published paper.

While depression has been extensively linked to Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia before, this study tracks timing in more detail and uses people with comparison illnesses as controls (rather than healthy people) to help rule out a broader explanation.

The researchers looked at 17,711 people over 12 years (2007 to 2019), all of whom developed Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia during that period. They matched them to controls: 19,556 people with rheumatoid arthritis, 40,842 with chronic kidney disease, and 47,809 with osteoporosis.

The association was strongest in Lewy body dementia, which the researchers suggest may relate to how the disease affects brain chemistry related to mood, and to its tendency to progress more aggressively than Parkinson's disease.

Based on the findings, it's possible that depression indicates some of the early brain changes – the fundamental neuron rewiring – that's going on as either neurological condition starts to develop.

In this study, the median age of diagnosis with Parkinson's disease or Lewy body dementia was 75. The researchers suggest that people who are diagnosed with depression for the first time late in life should also be screened for the early stages of neurodegeneration.

By including the other illnesses, the team helped to eliminate some of the other factors that might have been an influence here: in other words, showing that cases of depression weren't just down to living with a serious medical condition.

"Our findings align with those from prior studies, the majority of which have also observed increased prevalence and incidence of depression both prior to and following the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia," write the researchers. "However, most of these studies, with exceptions, have used control groups consisting of healthy individuals."

"Our comparison with other chronic conditions should, at least to some extent, control for the disability associated with the development and manifestation of Parkinson's disease and Lewy body dementia."

It's important to bear in mind that while this is a strong association, this type of study doesn't prove cause and effect. Something else related to both conditions, such as sleep problems, might be causing depression rather than the neurological damage, which future research could look into.

Parkinson's disease affects more than a million people in the US alone, typically affecting mood, memory, and motor functions due to the death of dopamine-producing neurons. Lewy body dementia, named after the clumps of protein that drive it, also degrades thinking, memory, and movement, and affects over a million people in the US.

Related: Major Review Reveals The Best Exercises For Easing Depression

Considering there's no cure for either condition, being able to use depression as an early warning sign may not seem useful. But spotting neurological damage earlier means support can be put in place sooner, treatment can be improved, and scientists have more opportunity to study the root causes of these diseases before they've fully taken hold.

"Given the established associations between depression, cognitive decline, and accelerated disease progression, early detection and treatment of depression in this patient population may be crucial," write the researchers.

"Integrating mental health assessments into routine neurological care may facilitate the timely initiation of antidepressant therapy or other appropriate interventions."

The research has been published in General Psychiatry.