Usually, when you're having trouble with bloating and stomach discomfort, you'd think it's probably something you ate.

But for one 42-year-old woman in Japan these symptoms turned out to be the result of a surgical error - she'd been carrying two gauzy surgical sponges inside her body for years.

According to a case report published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the patient had experienced abdominal bloating for some three years before showing up at a primary care clinic for investigation.

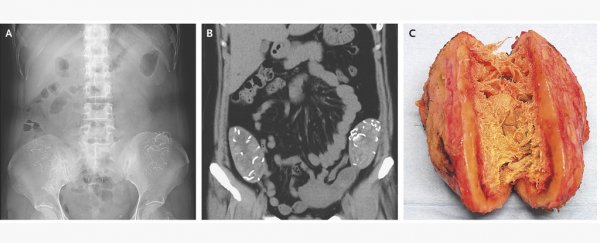

When the doctors pressed on her lower abdomen, they quickly discovered two masses on either side of the pelvis. The lumps weren't painful to the touch, but the team sent the patient off to do a CT scan.

"Computed tomography of the abdomen showed well-defined pelvic masses that contained hyperdense, stringy structures," the team writes in the report.

The only thing left was to open her up to see what those masses were.

Surgery revealed the stringy things were actually two gauze sponges ensconced in thick, fibrous shells that had partially attached themselves to the woman's colon and stomach tissue - not unlike some gross alien egg.

As it turns out, the patient had had two cesarean sections - one nine years before the event, and another one six years ago.

With no other abdominal surgeries in her history, it appears that she carried the sponges for at least six years, if not longer - which probably explains how they had time to grow into the fibrous blobs the doctors eventually found.

What's especially crazy is that this kind of error happens all the time - so often, in fact, the diagnosis even has a name: gossypiboma (Latin gossypium for 'cotton wool' and -oma for 'tumour').

Accidentally leaving something behind after surgery results in a retained surgical item (RSI), and the items in question can range from sharp things like suture needles and metal retractors to little bits of wire, broken pieces of instruments and so on.

The single most common RSI is the gauzy surgical sponge, which is probably tricky to spot in the wound once it's soaked up all that blood - besides, in a major operation a doctor could easily end up using 50-100 of those.

Surgeries do try and keep count of the sponges that go into a patient to prevent losing any, but mistakes still happen - according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists, between 4,500 and 6,000 US patients a year end up with an RSI, and two-thirds of those are either needles or sponges.

Doctors and stakeholders have been working on systems to prevent this problem, introducing innovative sponge-counting methods and even turning the job over to barcode technology.

According to Takeshi Kondo from Chiba University Hospital and lead author of the case study, many Japanese hospitals and clinics do imaging of the abdomen before closing a patient up, to prevent these problems.

Once the doctors removed the sponges, the woman made a full recovery and left the hospital after five days - but she didn't get justice for the egregious error made in one of her cesarean sections, both performed at the same clinic.

"Although she met the surgeon and told him (about) the retained foreign bodies, the surgeon did not admit his mistake on the grounds of lack of clear proof," Kondo told CNN.

Given that RSI's have led to patient deaths before, this woman certainly was lucky.

The case study was published in The New England Journal of Medicine.