Researchers believe they've made a significant step forward in preventing type 1 diabetes, by demonstrating how a pancreatic tissue that is usually killed off in diabetics can be protected by a cloak of sugar molecules.

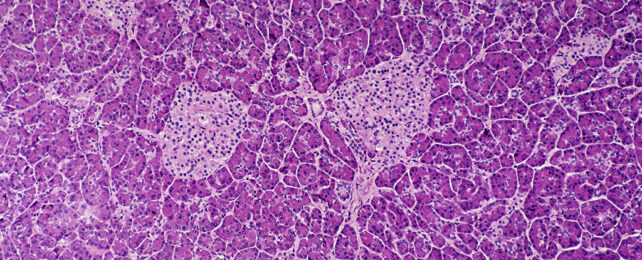

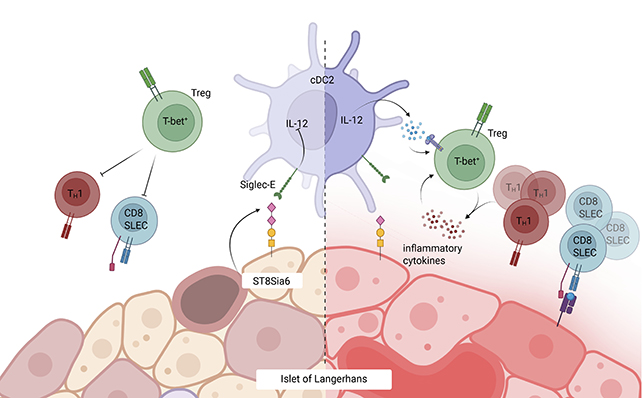

In a recent study, scientists from the Mayo Clinic in the US ran tests on female mice bred to be at risk of the mouse version of type 1 diabetes. A test group of mice had also been genetically engineered to produce more of a specific enzyme called ST8Sia6 in their pancreas's 'beta' cells, which in turn coated the tissue in a specific kind of sugar known as sialic acid.

It's the beta cells that produce insulin and help control blood sugar, and in type 1 diabetes, they're mistakenly attacked by the body's own immune system.

Related: First UK Patients Receive Diabetes Drug That Delays Symptoms by Years

In the untreated control group, 60 percent of the mice went on to develop type 1 diabetes, compared to 6 percent of mice in group with sialic acid on their beta cells – a 90 percent drop.

"Our findings show that it's possible to engineer beta cells that do not prompt an immune response," says immunologist Virginia Shapiro.

The sugar-coating subterfuge was discovered during research into cancer, with tumor cells observed using the ST8Sia6 enzyme and sialic acid to avoid destruction.

It's almost as if the sugar coating is a badge of authenticity, telling the body's immune system that these beta cells ought to be left alone. Even better, the immune system in the treated mice didn't seem to be negatively affected.

"Though the beta cells were spared, the immune system remained intact," says medical researcher Justin Choe.

"We found that the enzyme specifically generated tolerance against autoimmune rejection of the beta cell, providing local and quite specific protection against type 1 diabetes."

It's all very promising so far – albeit with the usual caveat in preclinical trials, which is that we're yet to see these same processes work in humans.

Part of the difficulty in finding a cure for type 1 diabetes is that we're still not sure exactly what triggers it, though we know the mechanisms through which beta cells are destroyed. It's thought that certain genetic and environmental factors could play a role in this specific immune system breakdown, but it's not clear what they are.

A condition that affects millions worldwide, type 1 diabetes requires constant monitoring of blood sugar levels and extra insulin via daily injections or an insulin pump to avoid serious complications.

"A goal would be to provide transplantable cells without the need for immunosuppression," says Shapiro.

"Though we're still in the early stages, this study may be one step toward improving care."

The research has been published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.