Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) negatively impacts the lives of millions of people worldwide, but more effective treatments could be on the way after researchers were able to identify specific neural biomarkers associated with the condition.

These biomarkers are patterns of brain activity present in people with OCD when they're acting compulsively, and which don't show up the rest of the time. While it's difficult to know exactly what these firing neurons are doing, their patterns could help understand the condition – and figure out how to treat it.

Led by a team from the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, the researchers looked at data from electrodes implanted in the brains of 11 people with chronic OCD, seeing how their brain activity changed over time in reaction to compulsive behaviors.

Related: US Woman Receives Revolutionary Brain Implant For OCD And Epilepsy

"For the first time, we have found a clear biological marker for OCD in the brain, a marker that we may be able to use in future treatments for OCD," says neuroscientist Tara Arbab of the University of Amsterdam.

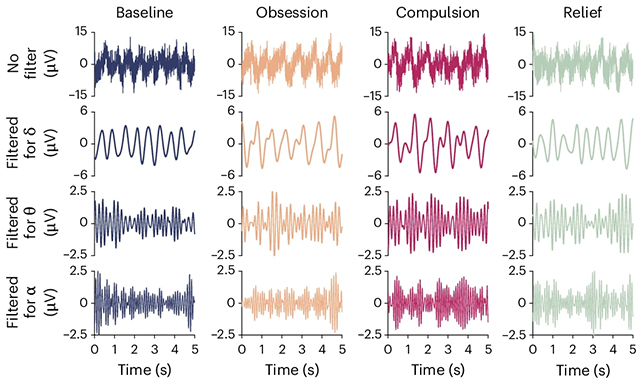

The patterns were put into four stages: baseline (sitting quietly), obsession, compulsion, and relief (post-compulsion). An obsession might be avoiding dirty surfaces, for example, with the compulsion being washing hands; these were tailored for each person.

Brain waves of two specific frequencies, alpha and delta, were noticeably prominent during compulsive acts. These electrical signals surged across all brain regions, and were observed for both mental and physical compulsions.

"In psychiatry, it is almost never possible to link a symptom so directly to brain activity," says Arbab. "This study shows that it is possible."

"We were able to measure deep brain activity with very high spatial and temporal precision. That's not possible with an fMRI or EEG."

The study participants had all received various forms of treatment for their OCD, without success. The implants used as brain monitors here had already been implanted prior to the study so that deep brain stimulation (DBS) could be tried as a therapy approach.

There are so many different parts to OCD that it's difficult to be certain about how it works: scientists have also looked at genetic influences and links to gut bacteria for clues about how the condition starts and how it persists. The severity of OCD can vary quite significantly from person to person.

As OCD treatments go, DBS isn't often used, and is still in an experimental stage. The idea is to control brain signaling to some extent, and it can work well – but questions remain about long-term effectiveness and potential side effects.

With the new information gathered in this study, the DBS approach could perhaps be made more targeted and effective. Further down the line, it might even be possible to artificially manipulate brain waves during compulsive episodes.

That's still some way off, but we do now know more about how OCD changes activity in the brain: where these changes happen, and how long they last for. These 'neural signatures' for the disorder are being slowly built up, piece by piece.

"We have been doing [DBS] in animal models for years, but in patients, this technology is still new," says Arbab.

The research has been published in Nature Mental Health.