The United Nations Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement (BBNJA) – nicknamed the 'High Seas Treaty' – comes into force on January 17, a massive milestone in efforts to conserve marine life in international waters.

The high seas are areas of the ocean that fall outside any one country's exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which are included in national jurisdiction. In most cases, EEZs include waters within 370 kilometers (230 miles) of a country's coastline.

These regions make up half of our planet's surface area, and two-thirds of its oceans. And while these vast waters teem with life and mineral riches, their lack of sovereignty has also historically meant a lack of legal protection. The BBNJA provides a long-overdue framework for governing and protecting the high seas.

Related: Deep-Sea Wonderland Found Thriving Where Humans Have Never Been

The treaty crossed a key threshold on September 19 last year, when Morocco became the 60th country to ratify it, making it legally binding within 120 days. Now, 81 UN member states have ratified the treaty, and that 120-day countdown is almost up.

"Perhaps most significantly, the Agreement creates a governance regime for establishing area-based management tools (e.g. marine protected areas) in the high seas," explained international environmental lawyer Eliza Northrop, of the University of New South Wales in Australia, when the treaty threshold was crossed.

"Already, governments are identifying potential areas for high seas marine protected areas, including sites like the Salas y Gómez and Nazca Ridges, the Sargasso Sea, and areas of the South Tasman Sea."

She says these early proposals will carry a lot of weight, setting the precedent for marine protected areas in international waters and, perhaps even more importantly, influencing the pace and scope of future conservation efforts. There's a lot at stake.

"Conversations about the high seas were historically driven by commercial interests, including shipping, industrialized fishing, and increasingly mining and prospecting," marine ecologists Kirsten Grorud-Colvert and Jenna Sullivan-Stack write in an editorial in Science.

Deep-sea biologist Paige Maroni, from the University of Western Australia, said the treaty has the potential to provide genuine protection for deep-sea and polar ecosystems, so long as it is enforced properly.

"Much of the deep sea is still poorly known, yet it is increasingly exposed to pressures such as mining, fishing, and climate change," Maroni told ScienceAlert. "The treaty has the potential to significantly accelerate deep-sea science by promoting international collaboration, data sharing, and coordinated research in areas beyond national jurisdiction."

Scientists have demonstrated again and again that well-designed and managed marine protected areas can safeguard sea life from carbon-heavy overfishing that has historically crashed fish stocks and wrought irreversible damage on ecosystems, along with "habitat-damaging fishing gear, mining, and oil and gas exploration and extraction," Grorud-Colvert and Sullivan-Stack explain.

The agreement also mandates that member parties carry out environmental impact assessments for any activity – such as fishing or mining – that might cause "substantial pollution or significant and harmful changes" to marine environments in international waters. This also applies to undertakings within their own borders, which may have flow-on effects in the high seas.

Related: We've Only Glimpsed 0.001% of Earth's Deep Seafloor, Study Reveals

Interestingly, the treaty also establishes a benefit-sharing mechanism for marine genetic resources. Only a few countries and corporations currently have the resources to collect and commercialize the oceans' genetic wealth (like the sea sponge that inspired chemotherapy drugs, for instance). The benefit-sharing mechanism requires member parties to share the proceeds instead.

"This mechanism embodies the principle that the high seas and their resources are the common heritage of humankind – not a frontier for exclusive exploitation," Northrop noted.

Whether the BBNJA successfully achieves these ambitions depends greatly on funding, which the BBNJA addresses by establishing three separate streams.

That includes a 'special fund' made up of annual contributions and payments from the treaty's participating states, as well as voluntary contributions from private entities; a voluntary trust fund to ensure developing nations' participation; and the preexisting Global Environmental Facility trust fund.

It also depends on global leaders' willingness to actually follow scientists' recommendations.

"My main concern is not the ambition of the treaty, but its implementation," Maroni told ScienceAlert. "The effectiveness of the High Seas Treaty will ultimately depend on enforcement, resourcing, and the willingness of nations to act on scientific advice."

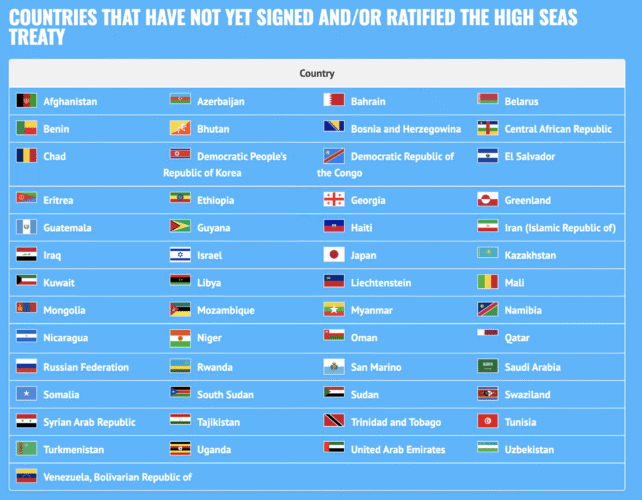

China, the European Union, Mexico, and Vietnam are among those to have both signed and ratified the agreement. Others, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, have signed but not yet ratified it.

"Science played an important role in crafting and ratifying the agreement," Grorund-Colvert and Sullivan-Stack write. "Now, as it is implemented, global leaders must ensure that scientific findings, rather than politics, continue to play the leading role."

A full list of states to sign and/or ratify the treaty is available at the United Nations Treaty Collection. The BBNJ is available in full here.