Scientists and health professionals are closely monitoring a rare virus known as Alaskapox after a fatal case popped up in a new area.

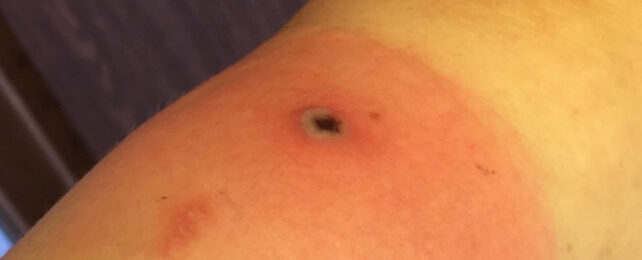

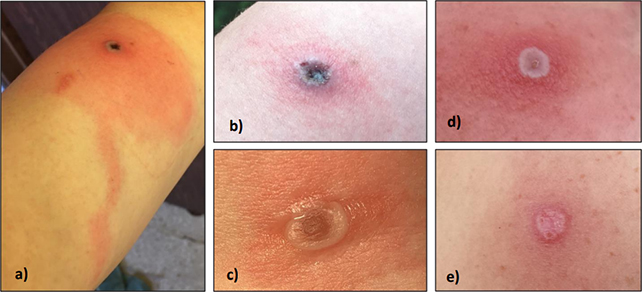

The few cases diagnosed since Alaskapox was first identified in 2015 have typically been associated with mild symptoms, including joint and muscle pain, swollen lymph nodes, and one or more bumps or pustules on the skin.

The virus usually clears up after a few weeks but can be more dangerous for people with weakened immune systems.

An elderly man on the Kenai Peninsula has become the first known individual to die as a result of Alaskapox. It's only the seventh case since it was first identified, but in a location more than 500 kilometers (311 miles) from the first, which was reported in Fairbanks, Alaska.

The patient in the fatal case reported a red sore under his right armpit, followed by burning pain sensations and feelings of fatigue.

It is believed the fact he was undergoing treatment for cancer may have contributed to his body being in a vulnerable state, and therefore at heightened risk of complications from the virus.

After being hospitalized in November, the patient died in late January, as per a State of Alaska Epidemiology bulletin.

The conclusion from health officials is that Alaskapox is more geographically widespread than previously thought and that more awareness of the risks is needed, especially for the immunocompromised.

From the evidence so far, it appears that Alaskapox spreads through small mammals, particularly red-backed voles and shrews. While humans can catch it from animals, there's been no sign of human-to-human transmission.

The virus is part of the orthopox group, of which smallpox is probably the most well-known – they're characterized by the way that they cause lesions (the 'pox') on the skin, as also happens with Alaskapox.

As per the bulletin, the man lived alone in a remote area, though he reported looking after a stray cat that frequently scratched him – this may be how the virus was transferred, though tests on the cat for orthopoxviruses came back negative.

New recommendations from the Department of Health in Alaska include getting clinicians familiar with the features of the virus and testing for it regularly – as well as advising those with suspected Alaskapox to keep lesions dry and covered, and to avoid touching them.

"It is likely that the virus is present more broadly in Alaska's small mammals and that more infections in humans have occurred but were not identified," explains a FAQ written by the Alaska Division of Public Health.

"More animal testing is occurring to better understand the distribution of the virus in animal populations throughout Alaska."