An invasive tick that feeds on humans, pets, livestock and wildlife is now making a new home for itself in the United States.

The Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) is a potentially disease-carrying, blood-sucking species native to East Asia.

Last year, however, this exotic pest was somehow found in the US state of New Jersey, hitching a ride on a sheep, thousands of kilometres from home.

Since then, this intrepid and opportunistic explorer has been popping up all over, in multiple different states, including New York, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Arkansas, Connecticut and Maryland.

It's the first invasive tick to emerge in the US in nearly 80 years, and researchers think it is here to stay.

A new study suggests that the steady and furtive creep of the Asian longhorned tick has only just begun.

"The Asian longhorned tick is a very adaptable species, especially in its native East Asia,"says lead author Ilia Rochlin, an entomologist at the Rutgers University Center for Vector Biology.

"The optimal tick habitat appears to be defined by temperate conditions--moderate temperature, humidity, and precipitation. These climatic conditions also support forested or shrubby vegetation, providing prime environment for ticks."

And unfortunately, these ideal conditions are found right across North America.

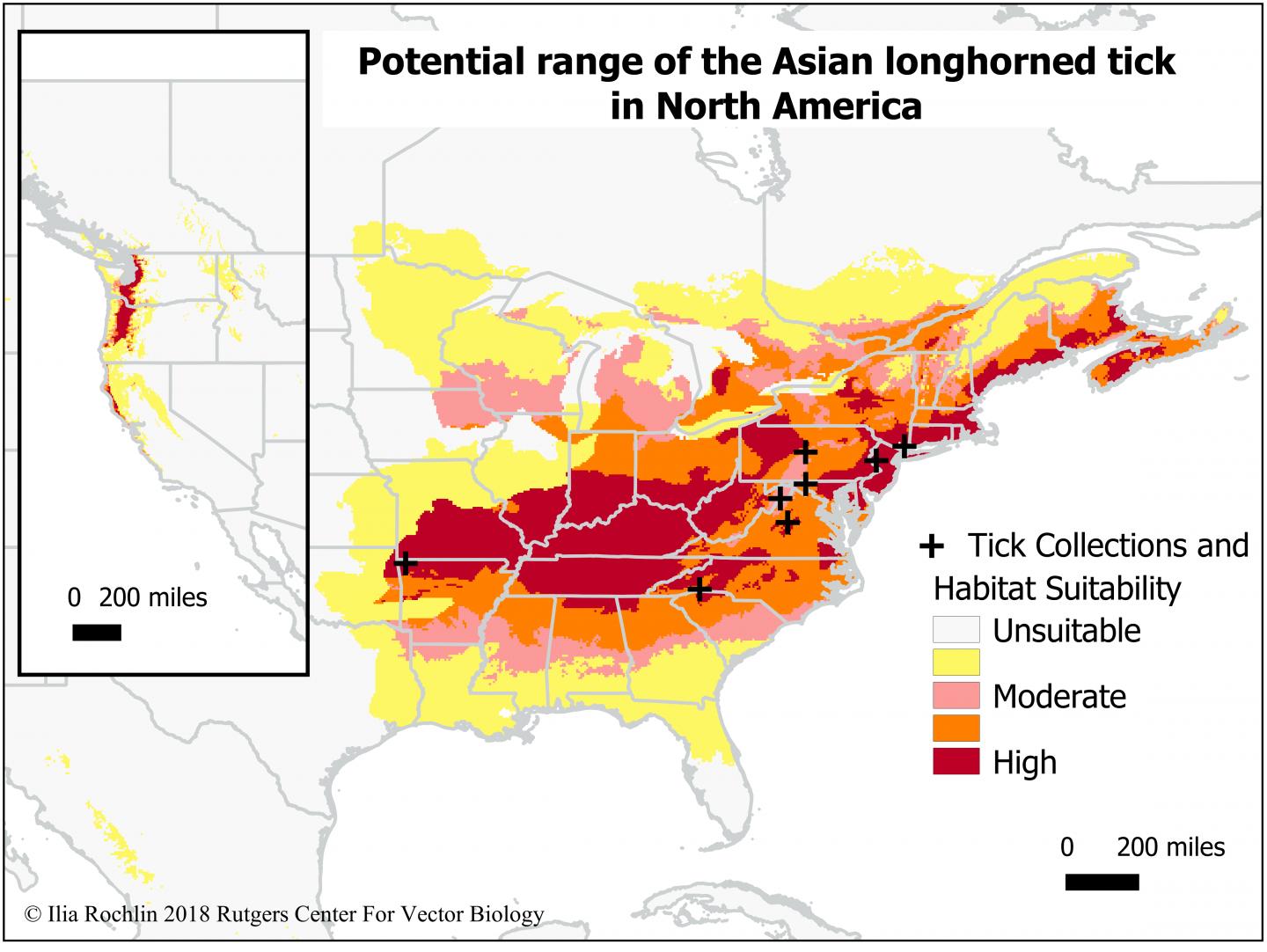

Using climate and environmental data from the tick's home in China, Japan and Korea, Rochlin created a statistical model that identifies similarly suitable habitats in the US and Canada.

The findings reveal that much of North America is a veritable breeding ground for the Asian longhorned tick, with moderate to high suitability.

Vast regions of this continent, including the west coast and especially the east coast, were found to boast ideal humid temperatures and subtropical broadleaf forests in which these ticks commonly flourish.

"Similar to China's mainland, this potential H. longicornis habitat in North America is limited by low temperatures in the north, by dry climatic conditions in the west, and by high temperatures in the south," the study concludes.

This leaves plenty of room for movement. Dipping down to northern Florida and stretching all the way up to southeastern Canada; tracing the Gulf coast as far as Louisiana; reaching inland to the Midwest and southeastern states; running along the northern coast of California and Oregon, and speckling the waterline of Washington.

The regions where this tick could potentially set up residence are immense.

The results are concerning, because this tick is notorious for carrying disease, and this puts all of its food sources in North America at risk, including goats, sheep, cattle, pigs, deer, cats, dogs, rats, mice, hedgehogs, birds and even humans.

At present, there is no evidence that the longhorned tick has transmitted any diseases in the US, but given its track record, expectations are not good, prompting the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC) to issue a warning about the invasive species last month.

In its homeland, this tick has been found to carry a severe, fever-inducing virus of the Phlebovirus genus. And incidentally, this emerging disease is closely related to the Heartland virus in the US, which is currently transported by the Lone Star tick.

"Introduction of a tick species that is a competent vector for a closely related virus should be a matter of concern for the public health agencies and requires further investigations," the study argues.

But perhaps the biggest worry has to do with livestock.

In Australia and New Zealand, where this invasive species has already set up camp, the Asian longhorned tick has been found to carry bovine theileriosis, which can result in costly production losses and high mortality. This blood-sucking tick can even cause a dairy cow's milk production to drop by as much as 25 percent.

Given the species' tiny size, its versatility and its ability to asexually reproduce, laying thousands of eggs at a time, Rochlin says that eradicating it from the US will be extremely difficult if not impossible.

The only thing we really can do at this stage is keep tabs on this parasite as closely as possible.

"The main question I am often asked is 'What can be done about ticks?' - and I don't have a good answer to that. While research and surveillance are important, we are in dire need of comprehensive tick-control strategy and new tools to carry it out," Rochlin says.

"Mosquito control has been very successful in this country, but we are losing the battle with tick-borne diseases."

This study has been published in the Journal of Medical Entomology.