In November of 2020, a freak wave came out of the blue, lifting a lonesome buoy off the coast of British Columbia 17.6 meters high (58 feet).

The four-story wall of water has now been confirmed as the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded.

Such an exceptional event is thought to occur only once every 1,300 years. And unless the buoy had been taken for a ride, we might never have known it even happened.

For centuries, rogue waves were considered nothing but nautical folklore. It wasn't until 1995 that myth became fact. On the first day of the new year, a nearly 26-meter-high wave (85 feet) suddenly struck an oil-drilling platform roughly 160 kilometers (100 miles) off the coast of Norway.

At the time, the so-called Draupner wave defied all previous models scientists had put together.

Since then, dozens more rogue waves have been recorded (some even in lakes), and while the one that surfaced near Ucluelet, Vancouver Island was not the tallest, its relative size compared to the waves around it was unprecedented.

Scientists define a rogue wave as any wave more than twice the height of the waves surrounding it. The Draupner wave, for instance, was 25.6 meters tall, while its neighbors were only 12 meters tall.

In comparison, the Ucluelet wave was nearly three times the size of its peers.

"Proportionally, the Ucluelet wave is likely the most extreme rogue wave ever recorded," says physicist Johannes Gemmrich from the University of Victoria.

"Only a few rogue waves in high sea states have been observed directly, and nothing of this magnitude."

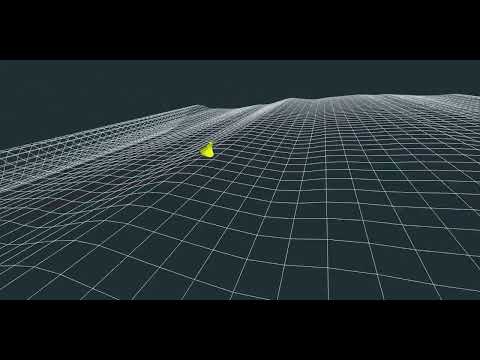

Today, researchers are still trying to figure out how rogue waves are formed so we can better predict when they will arise. This includes measuring rogue waves in real time and also running models on the way they get whipped up by the wind.

The buoy that picked up the Ucluelet wave was placed offshore along with dozens of others by a research institute called MarineLabs in an attempt to learn more about hazards out in the deep.

Even when freak waves occur far offshore, they can still destroy marine operations, wind farms, or oil rigs. If they are big enough, they can even put the lives of beachgoers at risk.

Luckily, neither Ucluelet nor Draupner caused any severe damage or took any lives, but other rogue waves have.

Some ships that went missing in the 1970s, for instance, are now thought to have been sunk by sudden, looming waves. The leftover floating wreckage looks like the work of an immense white cap.

Unfortunately, a recent study predicts wave heights in the North Pacific are going to increase with climate change, which suggests the Ucluelet wave may not hold its record for as long as our current predictions suggest.

"We are aiming to improve safety and decision-making for marine operations and coastal communities through widespread measurement of the world's coastlines," says MarineLabs CEO Scott Beatty.

"Capturing this once-in-a-millennium wave, right in our backyard, is a thrilling indicator of the power of coastal intelligence to transform marine safety."

The study was published in Scientific Reports.