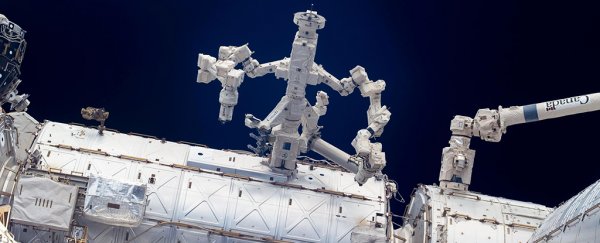

Even the International Space Station (ISS) needs a battery change every now and again, and the station just got its first battery refresh in 18 years, courtesy of the Special Purpose Dexterous Manipulator (SPDM) robot, or Dextre.

The four old nickel-hydrogen batteries that were just replaced date from the earliest days of the space station, which went into orbit in November 1998. These packs are an essential part of the solar power system on the ISS.

Dextre, with help from the astronauts currently on board the space station, isn't done yet though, and will continue its mission outside the ISS until all 48 of the original batteries are swapped out for 24 smaller and more efficient lithium-ion alternatives.

Writing on NASA's ISS blog, the space agency's Mark Garcia called the operation "a remarkable demonstration of robotic prowess", but we're still in the early stages of the process.

Some of the old nickel batteries will be stored on board the ISS but kept dormant, while others will be sent back towards Earth on the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle, to be burned up in the upper atmosphere.

On Friday, Commander Shane Kimbrough and NASA astronaut Peggy Whitson are heading out of the ISS on a spacewalk. They'll be installing adapter plates to temporarily stow the older batteries, among other duties.

After that, Dextre will continue removing old batteries and replacing them with newer versions during the course of next week.

In addition to battery upgrades, Dextre carries out a variety of maintenance tasks on the ISS. Designed and made in Canada, the robot handyman is famous enough to appear on banknotes in its home country.

Let's not be too hard on the nickel-hydrogen technology though – its time might be drawing to a close on the ISS, but it's been essential in powering the Mars Odyssey and the Hubble telescope, amongst other space probes.

But lithium-ion batteries – using the same type of battery tech that powers our phones – are smaller, more power-efficient, and cheaper to make, which are all important considerations when you're building something with deep space in mind.

They're also easier to manipulate into different designs, which is why NASA is now focussing on lithium-ion for the space programs of the future.

The fact that lithium-ion appears in so many consumer gadgets has helped its cause too, because so much investment and research has been diverted towards the technology in recent years.

As far as the ISS is concerned, batteries old and new are responsible for keeping the station powered up when it's not in direct sunlight. While the solar panels on the ISS are in sight of the Sun, about 60 percent of the collected energy is diverted to the batteries for storage.

In total, the four sets of arrays on the station can generate up to 120 kilowatts of electricity at peak times, which is enough to power more than 40 homes – and being able to store that energy until it's needed is crucial for the space station.

When the battery upgrade is complete, the new lithium-ion units should see out the remainder of the ISS's lifespan – which is expected to be about another decade or so, at which point it will be directed to its end… plummeting to a watery grave in the Pacific Ocean.