Giant African pouched rats are as clever as they are cute. Trained to wear little backpacks, they can rescue people from disaster areas in return for a treat.

They can also find landmines that need disarming, sniff out tuberculosis, and have even been recruited in the fight against wildlife poaching.

So handy are these intelligent mammals, we can't seem to breed enough of them. It's not just a problem with demand – the supply is also mysteriously limited.

While many fellow rodents are notorious for their ability to rampantly multiply, the pouched rats (Cricetomys gambianus) have proven frustratingly unprolific.

"We wanted to understand their reproductive behaviors and olfactory capabilities, because they have been so important in humanitarian work," explained behavioral ecologist Alex Ophir in 2019 when first looking into their breeding behavior.

Around a meter (3 feet) long from whiskers to tail-tip, the animals are more closely related to a genus of Madagascan rodents called antsangy, than true rats. Their life-span is also a relatively lengthy eight years, with some females holding off on breeding until they're four years old. Some will stop breeding again after a successful pregnancy.

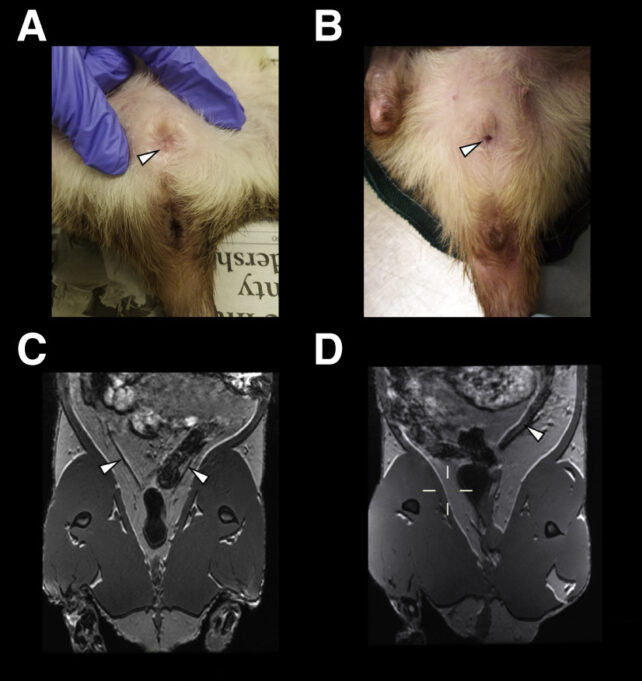

Baffled, researchers took a closer look and found to everyone's astonishment many of the female rats hadn't merely sworn off more kids, they'd closed shop, sealing off their vaginas.

In this morphological state the females had a smaller uterus and a fused vaginal opening. What's more, their urine featured a profoundly different chemical composition than their nestmates with normal vaginal openings who were actively breeding.

Cornell University ethologist Angela Freeman and colleagues observed 23 transitions in reproductive states in 17 out of the 51 female rats they observed. Some of the individuals transitioned more than once, and when one of the actively breeding females died of old age, seven of the colony members' vaginas opened up.

The team could not detect any changes in their environment, other than this social change.

"From this, we speculate that females might suppress the reproduction of others using volatile (pheromonal) olfactory signals," they write in their paper.

"You could interpret it as manipulation by one female to get other females to stop reproducing, and in effect, they'll often in these cases, start to contribute to the care of the dominant reproducing female," says Ophir.

This phenomenon is not unheard of in mammals, with naked mole rat queens feeding their subordinates their hormone filled poop to turn them into nannies. Reduced levels of luteinizing hormone prevent other female naked mole rats from ovulating.

Other mammals also have hormonally-modulated reproduction, such as those that keep their breeding seasonal. Physically closing off reproductive organs is an unusual trait for mammals and the hormones associated with breeding cycles in other rodents did not seem to determine which females were open for business in these giant African pouched rats.

"The fact that there is this naturally occurring ability to sort of change reproductive morphology and physiology suggests that things are probably a whole lot more plastic than we realize," says Ophir.

"If nothing else, it just provides another example that things aren't as dogmatically simple as people think."

This research was published in Current Biology.