The Environmental Protection Agency must strengthen its oversight of state drinking water programs to avoid a repeat of what happened in Flint, Mich., an agency watchdog said in a report Thursday.

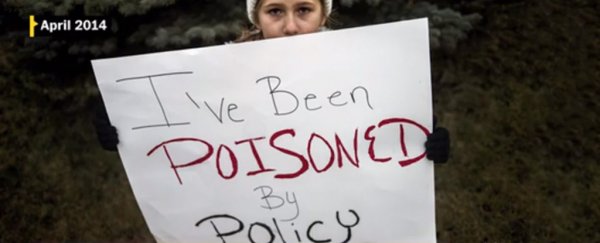

Sluggish federal reaction meant residents were exposed to lead-tainted water for far too long.

"While oversight authority is vital, its absence can contribute to a catastrophic situation," EPA Inspector General Arthur A Elkins Jr said in releasing the findings.

The report stated that "while Flint residents were being exposed to lead in drinking water, the federal response was delayed, in part, because the EPA did not establish clear roles and responsibilities, risk assessment procedures, effective communication and proactive oversight tools."

The EPA was not alone in its failure to address the crisis for a city of nearly 100,000, including exposing thousands of young children to lead.

In particular, state officials failed to implement proper treatments after Flint switched drinking water sources in early 2014 and, for months, ignored warnings from local residents about the deteriorating water quality.

The EPA's inspector general found that the federal government deserved significant blame for not more quickly using its enforcement authority to make sure state and local officials were complying with the Safe Drinking Water Act, as well as with federal rules that mandate testing for lead.

"EPA needs to learn from Flint and this report," said Mona Hanna-Attisha, the Flint pediatrician whose research in late 2015 first documented dangerously high lead levels in children's blood.

"All of the EPA lead standards are grossly inadequate and need to be updated to respect the science of 'no safe level' of lead exposure. Only then will we as a nation be able to fully protect the potential of our children from this preventable neurotoxin."

In particular, the report found the EPA's Region 5 office, which oversaw Michigan, "did not manage its drinking water oversight program in a way that facilitated effective oversight and timely intervention," and staffers in the region "lacked a sense of urgency."

In one notable failure, EPA scientist Miguel Del Toral drafted a report in June 2015 "that outlined concerns about lead in Flint's drinking water and the lack of corrosion control treatment. This report indicated the potential for serious human health risks and recommended potential EPA actions."

Even then, the agency's inspector general found, months passed before the EPA took action to address the growing crisis.

In Thursday's report, the EPA's inspector general offered nine recommendations, including putting in place controls to make sure states and localities are complying with lead testing regulations and properly treating water sources.

He also urged the EPA to revise and improve the much-criticized Lead and Copper Rule, which dictates how communities monitor for lead in drinking water. An overhaul of that rule has been underway for years, and the EPA has said it expects to unveil an updated version in 2019.

"EPA has closely reviewed the findings in the Inspector General's April 2018 draft report and agrees with their recommendations," agency spokeswoman Enesta Jones said in an email Thursday, adding that officials "have already taken steps to implement several of those recommendations and will continue to expeditiously adopt the rest. . . . The agency is actively engaging with states to improve communications and compliance with the federal Safe Drinking Water Act to safeguard human health."

For decades, Flint paid Detroit to have its water piped in from Lake Huron, with anti-corrosion chemicals added along the way.

But in early 2014, with the city under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager, officials switched to Flint River water to save money.

State officials failed to ensure proper corrosion-control treatment of the new water source.

That failure allowed rust, iron and lead to leach from aging pipes and wind up in residents' homes. Thousands of children were exposed to high levels of lead, which can cause long-term physical damage and mental impairment.

The crisis also obliterated residents' trust in government. For more than a year, residents and local activists complained of problems with the water, insisting it was causing rashes and other health problems.

Those warnings were largely ignored. Only later, after Hanna-Attisha detailed skyrocketing blood lead levels in some local children and reporters continued to publicize the problems with the water, did governments begin to take more aggressive action.

The EPA eventually used its emergency powers to demand action by the state and city. Its regional leader resigned - as the state's water quality director had done just weeks before.

The National Guard handed out bottled water, and water filters were distributed.

State and federal investigations began. The Michigan governor faced calls to resign, even as he apologized for the crisis, telling Flint residents in one State of the State address that "government failed you at the federal, state and local level."

Virginia Tech engineering professor Marc Edwards, a national authority on municipal water quality whose tests exposed the extent of Flint's lead contamination, told The Washington Post in early 2016: "People have realized they've been lied to, and EPA knew about this, and the state knew about this. What you really have as it spun out of control is a total loss of trust in government, which failed [residents] miserably. They don't believe a word that anyone tells them."

Since a task force began probing the debacle in early 2016, Michigan's attorney general has filed criminal charges against more than a dozen state and local officials - many of whom now face multiple felony counts - as well as civil suits against outside companies that worked with the Flint water system.

While much of the attention in Flint has focused on the lead-tainted water that exposed thousands of young children to potential long-term health risks, the crisis also has been linked to an outbreak of Legionnaires' disease that contributed to at least a dozen deaths.

Those cases ultimately led to the charges lodged against the state's top health officials, as well as its chief medical executive.

Science AF is ScienceAlert's new editorial section where we explore society's most complex problems using science, sanity and humor.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.