To find a cure for Alzheimer's disease, we need to understand how and where it gets started, and new research suggests we might be looking in the wrong place.

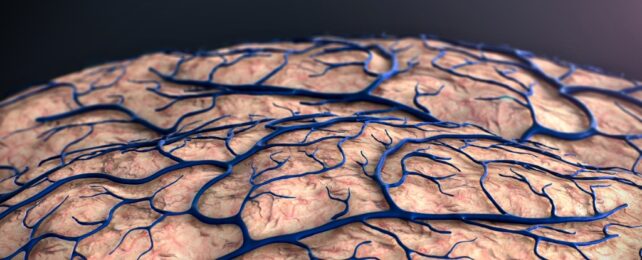

Scientists from the US and Germany have linked genetic risk for Alzheimer's and other brain diseases to the blood-brain barrier – the blood vessels and immune cells that surround and protect the brain.

While Alzheimer's is closely associated with abnormal clumps and tangles of proteins damaging neurons inside the brain, their findings suggest the initial trigger for the disease could be an outside intruder slipping through a compromised brain boundary.

Related: Blood-Brain Barrier 'Guardian' Shows Promise Against Alzheimer's

"When studying diseases affecting the brain, most research has focused on its resident neurons," says neuroscientist Andrew Yang, from the Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease in California.

"I hope our findings lead to more interest in the cells forming the brain's borders, which might actually take center stage in diseases like Alzheimer's."

Previous genetics studies found variations in DNA sequences linked with neurological conditions often occur not in genes that code for proteins, but in sections outside of them.

These flanking sequences often served to fine-tune the expression of nearby genes to help control the cell's activity.

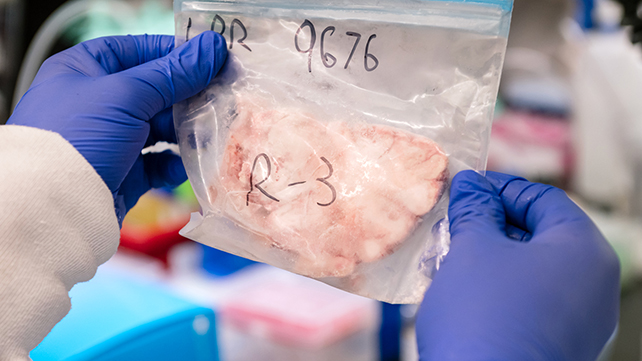

Yang and his colleagues developed a new genetic analysis technology called MultiVINE-seq. This method can isolate vascular and immune cells from brain tissue and measure their gene activity and chromatin accessibility (how 'open' DNA is to being used by the cell).

Putting the tech to work on 30 postmortem brain tissue samples from people with and without neurological disease, the researchers built up a comprehensive, layered picture of which genetic variations were linked to brain conditions such as Alzheimer's.

Many of these genetic variations were found in cells patrolling the borders of the brain, including endothelial cells that help manage access to the brain, and immune system T cells. Certain variants suggested inflammatory immune cells could be triggering or accelerating Alzheimer's.

"Before this, we knew these genetic variants increased disease risk, but we didn't know where or how they acted in the context of brain barrier cell types," says neuroscientist Madigan Reid, from the Gladstone Institute.

"Our study shows that many of the variants are actually functioning in blood vessels and immune cells in the brain."

Neurodegenerative diseases are complex and affected by many factors, so progress in fighting them is slow. However, this latest study gets us another step closer to understanding how diseases like Alzheimer's work.

Related: These 4 Distinct Patterns May Signal Alzheimer's According to Science

Previous research has already linked Alzheimer's disease to broader issues with the immune system, not just within the brain. We also know that other parts of the body may be involved, via how they message and interact with the brain.

The team also found that different genetic risk variants had different effects on the borders of the brain, depending on the disease – another important finding that can teach us more about various diseases, and how to develop treatments.

"This work brings the brain's vascular and immune cells into the spotlight," says Yang.

"Given their unique location and role in establishing the brain's relationship with the body and outside world, our work could inform new, more accessible drug targets and lifestyle interventions to protect the brain from the outside in."

The research has been published in Neuron.