Generations of ancient, solitary bees made a home within the tooth holes of a fossilized jawbone, which was recently uncovered in a cave on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.

It's the first time we've ever seen ancient bees taking up residence in the pre-existing cavities of a fossil, and it shows home really is what you make it.

Paleontologists believe the jawbone once belonged to a capybara-like rodent (Plagiodontia araeum), most likely transported to the cave in the grasp of an owl, which made a meal of the now extinct mammal and discarded its jawbone.

Related: A Wasp, Flower, And Fly Trapped in Amber Reveal 30-Million-Year Old Microcosm

Over the years, the jawbone's teeth loosened and scattered, as it was slowly buried beneath a fine clay silt.

There, in the holes left behind, called dental alveoli, a newly-described species of burrowing bee, Osnidum almontei, set up a multi-generational home.

We only know this because the unusually smooth surface inside one of these alveoli stood out to paleontologist Lazaro Viñola Lopez, who was digging up bones as part of his work at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

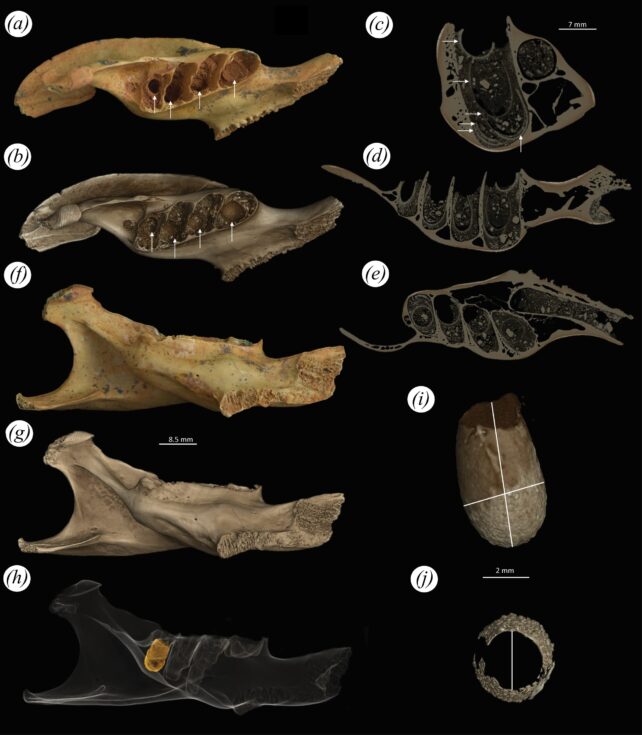

"Micro-computed tomography scans of the host bones show multi-generational use of the same cavity, suggesting repeated use and some degree of nest fidelity," Viñola Lopez and his colleagues explain in their published paper.

"Fidelity in the nesting behaviour of bees is linked to the consistency or specificity with which a bee species or individual selects and uses particular nesting sites or materials."

Once the researchers knew what to look for, they found many such examples of the bees' nesting cells within bones throughout the sediment, even one within the jawbone of a sloth.

These may be only trace fossils (ichnofossils) of O. almontei, but they tell a fascinating story of the bees' behavior.

"The cells of Osnidum almontei appear highly opportunistic, filling all bony chambers available in the sediment deposit," the team writes.

"Similarly, the high abundance of nests throughout the deposit indicated that this cave was used for a long period as a nesting aggregation area by this solitary bee."

The research is published in Royal Society Open Science.