A teeny tiny fossil found in the Scottish Highlands could be a missing link in the evolutionary history of animals.

Dated to around a billion years ago, the microfossil shows evidence of two distinctly different types of cells, and it seems to belong to an ancient organism somewhere between unicellular and multicellular animals. This makes it possibly the oldest fossil of its kind on record, a discovery that could provide insight into how and where animal life evolved.

"The origins of complex multicellularity and the origin of animals are considered two of the most important events in the history of life on Earth, our discovery sheds new light on both of these," said palaeobiologist Charles Wellman of the University of Sheffield in the UK.

"We have found a primitive spherical organism made up of an arrangement of two distinct cell types, the first step towards a complex multicellular structure, something which has never been described before in the fossil record."

The fossils - measuring under 30 micrometers across - were found in the Diabaig Formation at Loch Torridon, an assemblage containing microfossils from a lacustrine setting dating to 1 billion years ago. The stone deposits from the ancient lakebed have kept the fossils in a remarkable state of preservation, right down to the subcellular level.

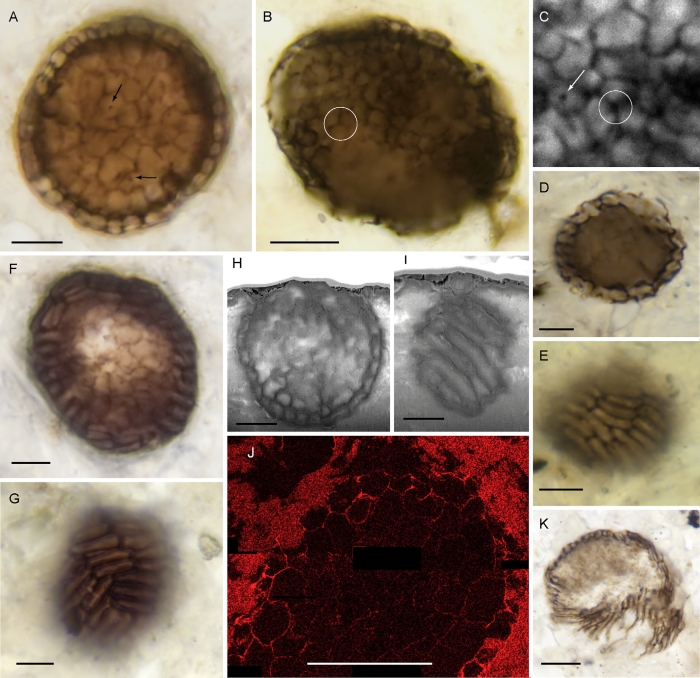

The new organism, named Bicellum brasieri, was preserved so well in multiple fossils, that its structure was clearly visible. In its mature form, it appears to have consisted of a tiny sphere of tightly packed, roughly spherical cells (known as a stereoblast), surrounded by a differentiated outer single layer of elongated, sausage-shaped cells.

Bicellum brasieri. (Strother et al., Curr. Biol., 2021)

Bicellum brasieri. (Strother et al., Curr. Biol., 2021)

Two populations, however, show a mixture of cell types throughout the stereoblast. The researchers have interpreted this as a more juvenile form of the organism during the process of differentiation, with the sausage cells developing and in the process of migrating to the exterior of the stereoblast.

Other multicellular organisms from around the same time have been identified, including fungus and algae, but the morphology of Bicellum, the researchers said, is more consistent with Holozoa, the group that contains animals and their closest unicellular relatives.

This means that Bicellum could be an important piece of Earth's evolutionary puzzle - helping us not just understand the transition from unicellular holozoa to more complex multicellular animals, but the origins of certain traits exhibited by complex animals.

"Biologists have speculated that the origin of animals included the incorporation and repurposing of prior genes that had evolved earlier in unicellular organisms," explained paleobotanist Paul Strother of Boston College.

"What we see in Bicellum is an example of such a genetic system, involving cell-cell adhesion and cell differentiation that may have been incorporated into the animal genome half a billion years later."

The discovery could also help fill in some gaps about where specific lifeforms evolved. One of the biggest debates raging about the origins of life is whether it occurred in the salty oceans or freshwater terrestrial lakes.

Given that evidence is mounting for a very, very soggy early Earth as late as 3.2 billion years ago, and fossils have been found dating back 3.5 billion years, a marine environment seems likely for the very first microbial life, but Bicellum suggests that lakes were important too.

"The discovery of this new fossil suggests to us that the evolution of multicellular animals had occurred at least one billion years ago and that early events prior to the evolution of animals may have occurred in freshwater like lakes rather than the ocean," Wellman said.

Like many, many processes in this wonderful world of ours, it's likely that a complex mix of ingredients contributed to the evolution of the Earth we know and love today. The team hopes that the Diabaig Formation may contain even more clues to understanding the fascinating story.

The research has been published in Current Biology.