Archaeologists have discovered evidence of unique early Neolithic burial practices in Galería del Sílex in Spain, following an analysis of ceramic vessels found with human remains in two pits.

Representing an early instance of diverse Neolithic funerary customs deep within the Iberian Peninsula interior, the finding draws attention to the Atapuerca Mountains as a significant frontier for early humans finding a new home in the area.

"The new evidence… illustrates that it could have been used as a funeral gallery whose use extended from the Early Neolithic, throughout the Chalcolithic, and lasted until the beginning of the Bronze Age," writes a team led by archaeologist Antonio Molina-Almansa from the University of Alcalá in Spain.

Neolithic 'pioneers' in the heart of Iberia left few traces of their funerary rituals. Moving frequently in small groups, little evidence remains of their methods for respectfully disposing of their dead.

Throughout what is now France, Portugal, and Andalusia, communities of the same period often took to interring their loved ones in caves when they passed. Yet on the Spanish peninsula, early Neolithic customs among those who began to settle in one place involved burying the dead in the ground.

The findings in Galería del Sílex provide a stark contrast to this practice.

Found in 1972, the cave features wall paintings and rock engravings, with fragments of faunal remains, human remains, and ceramics scattered throughout.

The two sets of human remains analyzed in this study are notable because each was placed at the bottom of two separate pits located more than 300 meters (984 feet) from the entrance.

"Galería del Sílex is an extraordinary site," the researchers write, "due to the fact that it was sealed at the end of the Bronze Age and has remained intact to the present day."

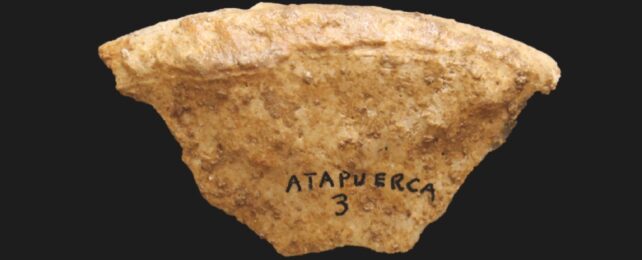

All human remains found at the site were previously assigned to the Bronze Age, but the presence of ceramic vessels dating back to the Early Neolithic found alongside the human remains in the two pits (known as Sima A and Sima B) prompted a reevaluation.

Radiocarbon dating on human teeth and bones from four different individuals found in the two pits provided an interesting correction. While one Sima A's body was indeed alive during the initial Bronze Age, sometime between 1880–1690 BCE, the other three human remains dated to between 5307 and 4897 BCE, putting them in the early Neolithic period.

The remains of one of the early Neolithic individuals, determined by the team to be a young girl aged 13 to 14, appeared to have been carefully placed in Sima A next to six ceramic vessels. The researchers think the girl was intentionally buried with the vessels as funerary offerings.

Molina-Almansa and team suggest this implies the people who used the Galería del Sílex cave were among the first in the region to develop complex funerary practices, with the deliberate placement in the cave and away from the entrance appearing to be unusual for this time.

"There were only two known caves in this area with Early Neolithic human remains," they write. "In both caves, human remains appeared in domestic contexts suggesting there was no special place reserved for the burial of their dead."

The fact that the individuals' graves were in a different location suggests there may have been something special about the area, which should be considered representative of the kinds of places our more nomadic ancestors would have elected to build more permanent settlements in.

"There is no doubt that it was used for funerary purposes," they explain, "given the great distance between the location where human remains were deposited and the ancient cave entrance."

The new analysis of Galería del Sílex provides a valuable glimpse into the lives of the earliest Neolithic people in the Iberian Peninsula.

It seems that these people were part of a complex and sophisticated society with a rich culture and belief system.

The study has been published in Quaternary Science Reviews.