A new fossil discovery has revealed that New Zealand's ancient monster penguins were not the only human-sized, flightless birds waddling around our planet tens of millions of years ago.

Recent findings in North America and Japan suggest there were giant penguin-like creatures plodding across the Northern Hemisphere, too. And these birds may have been even bigger.

The strange thing is, the now-extinct group of birds, known as plotopterids, are not related to penguins at all - but they look remarkably similar, and probably used their flipper-like wings in similar ways.

The earliest penguin ancestors first made their appearance a little more than 60 million years ago around what is today New Zealand. Plotopterids developed in the Northern Hemisphere much later than their southern counterparts, only appearing between 37 and 34 million years ago, and disappearing altogether 10 million years after that.

"These birds evolved in different hemispheres, millions of years apart, but from a distance you would be hard pressed to tell them apart," says zoologist Paul Scofield, a curator at the Canterbury Museum.

"Plotopterids looked like penguins, they swam like penguins, they probably ate like penguins – but they weren't penguins."

In a fascinating twist, this group of ancient flightless birds is more closely related to modern-day birds that fly just fine - boobies, gannets, and cormorants. In the past few years, we've come to understand a lot more about plotopterids, but this is the first time their anatomy has been compared in detail to ancient penguins.

Analysing the fossilised remains of 16 individual plopterids side by side with five representatives from three ancient penguin species, the researchers found many striking similarities along with a few sizable differences.

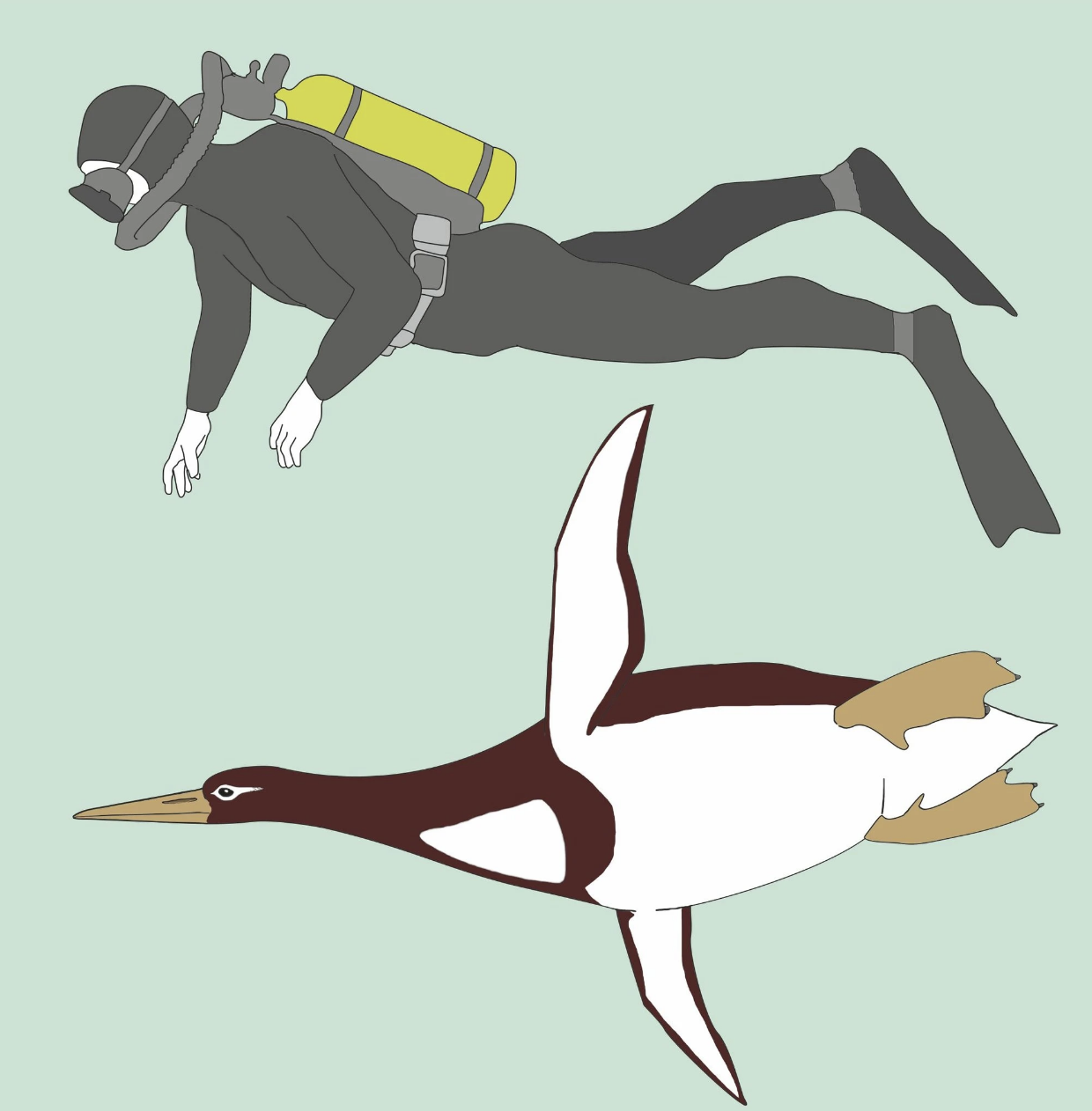

Both plotopterids and ancient penguins had long beaks embedded with slit-like nostrils, comparable chest and shoulder bones, and similar wings. But while some ancient penguins towered at 1.8 metres (6 feet), the largest plotopterids stood over 2 metres tall.

It's hard to imagine a bird, larger than a human, diving through the water, but it seems that was once a reality in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere.

(Mayr/Senckenberg Research Institute)

(Mayr/Senckenberg Research Institute)

Above: Artist's rendition of Kumimanu biceae, an extinct giant penguin, alongside a human diver.

Even though plotopterids have large webbed feet like penguins, the authors think they probably swam underwater relying mostly on their wings as flippers, judging by their anatomy.

"Wing-propelled diving is quite rare among birds; most swimming birds use their feet," says ornithologist Gerald Mayr of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt.

"We think both penguins and plotopterids had flying ancestors that would plunge from the air into the water in search of food. Over time these ancestor species got better at swimming and worse at flying."

The fact that this happened in distantly related organisms, millions of years apart and on opposite sides of the globe, is truly remarkable. It's a case of what scientists call 'convergent evolution', where similar traits develop in distinct species under similar environmental conditions.

Anatomical comparison of plotopterids and ancient giant penguins. (Mayr et al., Journal of Zoological Systems, 2020)

Anatomical comparison of plotopterids and ancient giant penguins. (Mayr et al., Journal of Zoological Systems, 2020)

In this case, two separate groups of flightless birds developed the anatomy they would need to forage for food deeper and deeper underwater. It just turned out to be remarkably similar.

"We therefore hypothesise that plotopterids and penguins had ancestors which performed aerial plunges to submerse into the water and to reduce the energetic costs for reaching greater depths," the authors write.

We'll need more digging to find out why one lineage of these remarkable birds survived, while the other passed into oblivion.

The study was published in the Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research.