Severed arms and brutalized skeletal remains recovered from pits at two 6,000-year-old archaeological sites in northeastern France suggest the region's inhabitants turned torture into a public spectacle to celebrate their victories.

A study on the remains offers evidence that the severed upper arms may have been taken as war trophies, while the excessively mutilated bodies were savagely slaughtered in a ritualized ceremony meant to dehumanize the enemy.

Describing the brutality to Owen Jarus at Live Science, archaeologist Teresa Fernández-Crespo from the University of Valladolid in Spain explains the "lower limbs were [fractured] in order to prevent the victims from escaping, the entire body shows blunt force traumas and, what it is more, in some skeletons there are some marks – piercing holes – that may indicate that the bodies were placed on a structure for public exposure after being tortured and killed."

These excessively violent killings may have been performed in full public view in a central community space, as a structured, ritualized form of ancient war propaganda to humiliate the enemy while strengthening social unity among the victors.

Related: Human Bones Reveal Evidence of One Horrifying Cannibalistic Feast

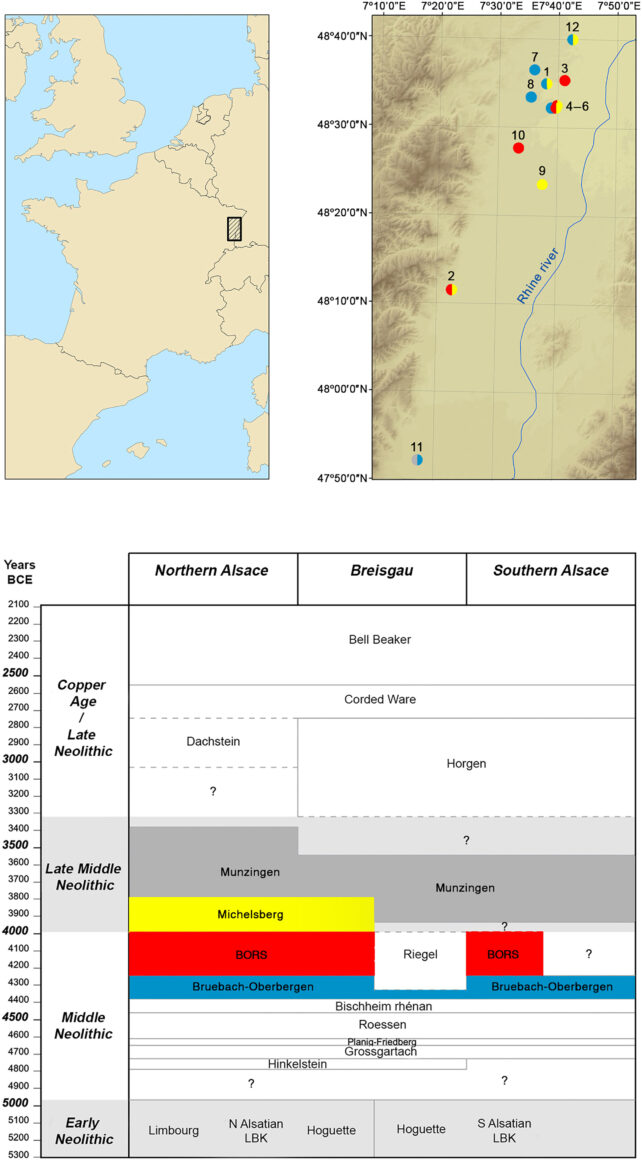

A total of 14 skeletons and a number of upper left limbs were recovered from two pits at Achenheim and Bergheim, which are located in Alsace, northeastern France. Dated to the late Middle Neolithic around 4300 to 4150 BCE, they lived during a period that saw an influx of migrants, invaders, and raiders from the greater Paris Basin, sparking wars of conquest among disparate tribes.

To trace the origins of both the slaughterers and the slaughtered, the researchers performed a multi-isotope analysis on a selection of the teeth and bones, using signature ratios of lighter and heavier versions of key elements to infer the origins, diet, and social rankings of the dead.

The researchers analyzed the remains of 82 humans, including the pits' "victims" and individuals from the region termed "non-victims", who were found in traditional burials. The researchers also analyzed remains from 53 animals and 35 modern plants to establish a regional baseline.

The analysis revealed that the severed arms belonged to members of nearby invading groups, and may have been taken by locals as war trophies.

While war trophies aren't uncommon in martial history, an upper arm appears to be a rare choice, with heads and hands more typical prizes found in the record. The severed upper arms may have even been "preserved [by being] smoked, dried, or embalmed" to be shown off for an extended time, the researchers claim.

In contrast, the whole skeletons belonged to individuals from a different place, possibly southern Alsace, suggesting they were captives that were brought back to the village, tortured, and then executed. They may have been deposited into the pits (along with the severed arms) during a closing ceremony to signal triumph, revenge, and the restoration of honor for allies fallen or injured in battle.

As an alternative hypothesis, based on evidence from Indigenous North American communities, all the victims may have been captured alive. Those who survived the mutilations may have "been retained as slaves or even adopted" by families who suffered casualties during the conflict, the authors propose.

"It may not be coincidental that in both sites severed upper limbs show isotope values consistent with northern Alsace and most skeletons of killed individuals with southern Alsace, which, if actually translated to different identities, might supply a reason for the differential treatment of captives," the researchers state.

Additionally, the ritualized killings may have been a votive offering meant to appease the ancestors or 'gods' who aided the victors in their conquest.

"These findings speak to a deeply embedded social practice – one that used violence not just as warfare, but as spectacle, memory, and assertion of dominance," says archaeologist and study co-author Rick Schulting, of Oxford's School of Archaeology.

In the grander scheme of history, this was a pyrrhic victory. The brutalizers then became the brutalized and supplanted by another group of people, as so often happens.

This research is published in Science Advances.