Some ant queens can produce offspring of more than one species – even when the other species is not known to exist in the nearby wild.

No other animal on Earth is known to do this, and it's hard for even scientists to believe.

"It's an absolutely fantastic, bizarre story of a system that allows things to happen that seem almost unimaginable," evolutionary biologist Jacobus Boomsma from the University of Copenhagen told Max Kozlov at Nature.

Some queen ants are known to mate with other species to produce hybrid workers, but Iberian harvester ants (Messor ibericus) on the island of Sicily go even further, blurring the lines of specieshood.

These queens can give birth to cloned males of another species entirely (Messor structor), with which they can mate to produce hybrid workers.

Related: Ant Queens Practice 'Hygienic Cannibalism' Out of Tough Love

Their reproductive strategy is akin to "sexual domestication", the researchers say. The queens have come to control the reproduction of another species, which they exploited from the wild long ago – similar to how humans have domesticated dogs.

In the past, the Iberian ants seem to have stolen the sperm of another species they once depended on, creating an army of male M. structor clones to reproduce with whenever they wanted.

This rid them of the need for nuptial flights to find other species. They had what they needed right at home.

According to genetic analysis, the colony's offspring are two distinct species, and yet they share the same mother.

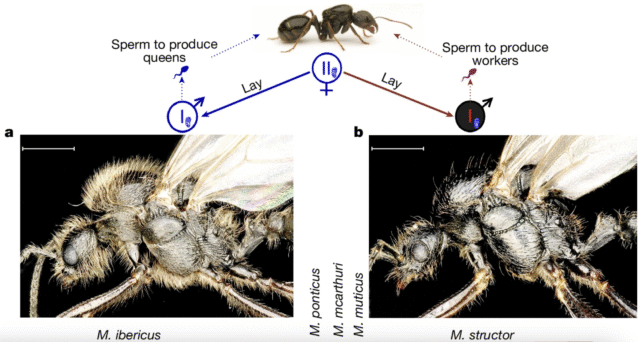

Some are the hairy M. ibericus, and the others the hairless M. structor – the closest wild populations of which live more than a thousand kilometers away.

The queen can mate with males of either species in the colony to reproduce. Mating with M. ibericus males will produce the next generation of queen, while mating with M. structor males will result in more workers. As such, all workers in the colony are hybrids of M. ibericus and M. structor.

The two species diverged from each other more than 5 million years ago, and yet today, M. structor is a sort of parasite living in the queen's colony. But she is hardly a victim.

The Iberian harvester queen ant controls what happens to the DNA of her clones. When she reproduces, she can do so asexually, producing a clone of herself. She can also fertilize her egg with the sperm of her own species or M. structor, or she can 'delete' her own nuclear DNA and use her egg as a vessel solely for the DNA of her male M. structor clones.

This means her offspring can either be related to her, or to another species. The only similarity is that both groups contain the queen's mitochondrial DNA. The result is greater diversity in the colony without the need for a wild neighboring species to mate with.

It also means that Iberian harvester ants belong to a 'two-species superorganism' – which the researchers say "challenges the usual boundaries of individuality."

The M. structor males produced by M. ibericus queens don't look exactly the same as males produced by M. structor queens, but their genomes match.

Entomologist Jessica Purcell, who was not involved in the study, agrees that these M. structor males are not technically hybrids. "Instead," she writes in a News and Views article in Nature, "I tentatively suggest that these M. structor males have become an integral part of M. ibericus populations."

"The inclusion of an entire genome from one species in the offspring of the population of another could be viewed as analogous to a system known as horizontal gene transfer," she adds, "yielding a new, combined genome and a distinct genetic lineage."

The study was published in Nature.