As effective as antibiotics often are at helping us fight off infection and the associated bacteria, they might also be reducing the bacteria-killing power of the body's own immune cells at the same time, according to new research.

That could significantly change the way we use antibiotics to treat infections in the future, as well as giving us clues to dealing with the increased antibiotic resistance we're seeing – the way that bacteria are adapting to stay one step ahead of our drugs.

The team of researchers carried out their studies on mice, so it remains to be seen whether the same antibiotic side effects are happening in humans as well. We already know that antibiotics can sometimes kill off "good" bacteria while fighting an infection, but this is a previously unexplored side effect.

"Antibiotics interact with cells, particularly immune cells, in ways we didn't expect," says one of the team, Jason Yang from the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard in Massachusetts.

"And the biochemical context, altered by antibiotics and cells in the surrounding tissue, matters when you're trying to predict how a drug might work in different people or in different infections."

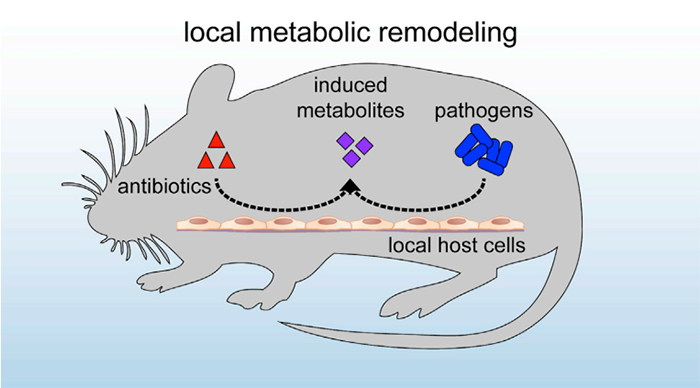

The antibiotics restricted the immune system in mice. (Cell Host & Microbe)

The antibiotics restricted the immune system in mice. (Cell Host & Microbe)

The study involved mice infected with E. coli bacteria and given a common antibiotic called ciprofloxacin, in doses comparable to those humans would get.

When analysing the biochemical changes in the animals, the researchers found a shift in the metabolites controlling metabolism: they were acting directly on the mice tissue to make the E. coli more resistant to ciprofloxacin.

What's more, by limiting the respiratory activity in the immune cells of the mice, exposure to antibiotics restricted the immune system's own ability to battle E. coli. The macrophages or large white blood cells became less effective at killing off the bacteria.

"You generally assume that antibiotics will significantly impact the bacterial cells, and yet here they seem to be triggering responses in mammalian cells," says lead researcher James Collins, from the Broad Institute.

"The drugs are producing changes that are actually counterproductive to the treatment effort. They reduce the bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics, and the drugs themselves reduce the functional benefit of the immune cells."

All of which means antibiotics could be having a more profound effect than we thought on the chemical processes going on in cells, and that in turn might have a big impact on how effective treatments turn out to be.

But if we can get to the bottom of why this is happening then we might be able to put the brakes on antibiotic resistance in the future.

There's also the issue of how far antibiotics could be reducing the capabilities of the immune system to do its job, with or without extra drugs.

The idea isn't a totally new one: research from last year found that antibiotics could harm the human immune system in some way, though in that case it was the gut microbiome that was affected, and the exact processes weren't clear.

More research is now going to be needed to see whether these changes in mice happen in human beings as well – so far we just have data for one infection and one antibiotic.

"We need to do additional animal studies under a broader range of conditions with a broader range of antibiotics, and potentially measure metabolites in human patients undergoing treatment, to see what else might be happening," says Collins.

The findings have been published in Cell Host & Microbe.