The taming of fire is credited with sparking humanity's evolutionary journey towards our modern levels of intelligence. Fire gave early humans access to a broader range of safe foods, fueling the development of larger brains and paving the way for the birth of Homo sapiens, so the cooking hypothesis goes.

A new discovery of baked sediments, artifacts, and pieces of firelighting pyrite in a UK claypit suggests that humans already had the capacity to create fire more than 400,000 years ago.

"This extraordinary discovery pushes this turning point back by some 350,000 years," says British Museum archaeologist Rob Davis.

"The implications are enormous. The ability to create and control fire is one of the most critical turning points in human history, with practical and social benefits that changed human evolution."

Related: Modern Humans Thrived While Neanderthals Disappeared, But Not Due to Our Brains

Researchers suspect fire use began opportunistically, with humans harvesting flames from wildfires. Evidence of this sort of fire use dates back more than 1 million years, a practice that may have flourished for meat preservation and other cooking.

However, the ability to start fires rather than maintain pre-existing ones likely arose later.

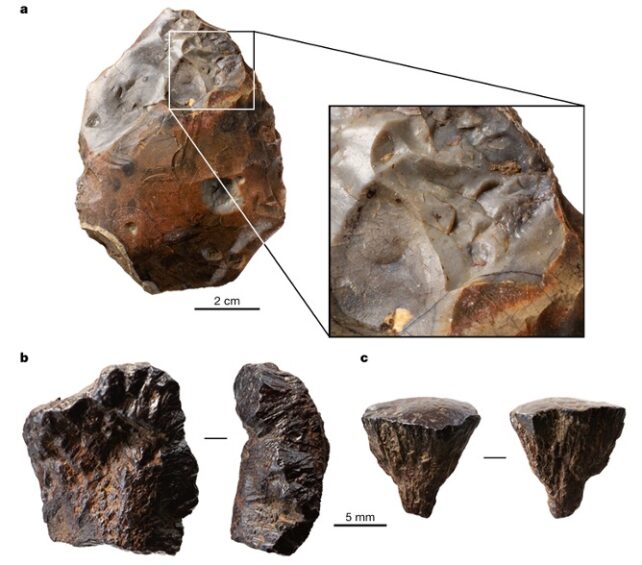

Previously, the earliest direct evidence for deliberate human-made fire was only 50,000 years old. A 2018 analysis of handaxes discovered in France suggested they were repeatedly struck against a mineral such as pyrite – a process that would create sparks.

Now, Davis and colleagues have identified two small fragments of oxidized pyrite at Barnham, a village in the UK. One of these shards was found close to heated artifacts, including four heat-shattered flint handaxes and a hearth of reddened sediment.

"Geological studies show that pyrite is locally rare, suggesting it was brought deliberately to the site for fire-making," the researchers write in their paper.

Tests of the baked sediments also showed that their properties most likely resulted from repeated heating, consistent with human use – a campfire – and not a one-off burn.

The fire starters in Palaeolithic England were likely Neanderthal, another indication that our shyer cousins were capable of complex behaviors, including abstract thought and technological advances.

The ability to create fire would have enabled humans to feed and bond in larger groups. Fire also gave our early ancestors access to new technologies, like the creation of glue for more advanced tools.

"Year-round access to fire would have provided an enhanced communal focus, potentially as a catalyst for social evolution," Davis and team conclude.

"It would have enabled routine cooking, could have expanded the consumption of roots, tubers, and meat, reduced energy required for digestion, and increased protein intake.

"These dietary improvements may have contributed to an increase in brain size, enhanced cognition, and the development of more complex social relationships."

This researcher was published in Nature.