Out-of-the-ordinary archaeological finds never fail to fascinate us as we dig into the past – like the prehistoric potato granules unearthed in Utah, which experts say could be up to 10,900 years old.

To be more precise, these are starch granules from the Solanum jamesii plant, which produces small wild potatoes, and they could help us make the potatoes of today more resistant to drought and disease.

On top of that, this looks to be the first example of a domesticated potato plant (one made safe to eat) appearing in North America, giving historians new insight into the diets and cooking methods used by our ancient ancestors.

"This potato could be just as important as those we eat today not only in terms of a food plant from the past, but as a potential food source for the future," says lead researcher Lisbeth Louderback from the University of Utah.

Potatoes from S. jamesii aren't like the ones you'll be used to buying from the grocery store, which are descended from the Solanum tuberosum plant first domesticated in the South American Andes more than 7,000 years ago.

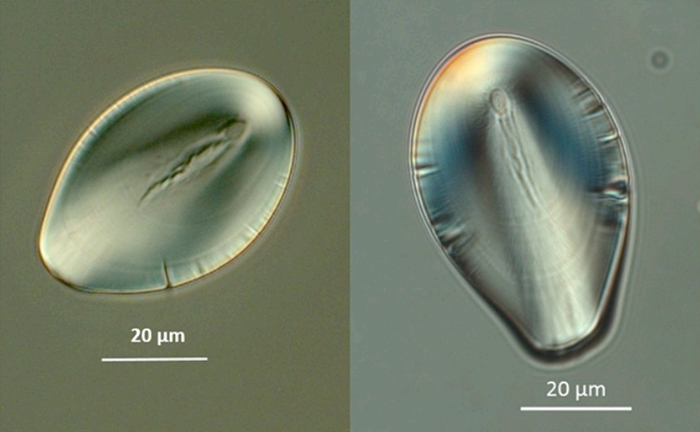

Some of the granules matched to wild potatoes. Credit: University of Utah

Some of the granules matched to wild potatoes. Credit: University of Utah

Though they're rare, S. jamesii potatoes are still grown and eaten in Utah's Escalante region today, and have a nutty flavour when properly prepared – it's just that no one realised how far their history went back.

The starch granules were discovered on ancient stone cooking tools dug up at the North Creek Shelter site in the Escalante valley. Having initially puzzled experts, the microscopic concentric circles on the granules were eventually matched to S. jamesii.

We know that these types of potato were eaten by several Native American tribes, including the Apache, the Navajo and the Hopi. They're also highly nutritious, packing in more protein, zinc, calcium, and iron than S. tuberosum.

However, In Utah the potato plant is only found in isolated sites close to archaeological digs, which suggests the tubers were brought to the area by outsiders.

All of this new information helps archaeologists and historians in their studies of life as it might have been tens of thousands of years ago, with studies up until this point putting the first potato use in this part of the world at a later date.

Now the researchers want to make sure the S. jamesii plant survives for future generations, as well as mine its DNA to look for genes resistant to drought and disease, which could be helpful in diversifying our current potato crops.

"It's hard to persuade the general public to care about rare plants," says one of the team, Bruce Pavlik from the University of Utah. "But this one has a real history associated with native people, with pioneers, with folks living though the depression and with the residents in Escalante today."

Indeed the region was known as "Potato Valley" to early settlers, a name and a meaning that's been lost down the generations.

"The potato has become a forgotten part of Escalante's history," says Louderback. "Our work is to help rediscover this heritage."

The research has been published in PNAS.

The team also put together a video covering the findings, which you can see below: