A secret text has been discovered in Türkiye, scattered among tens of thousands of ancient clay tablets, which were written in the time of the Hittite Empire during the second millennium BCE.

No one yet knows what the curious cuneiform script says, but it seems to be a long-lost language from more than 3,000 years ago.

Experts say the mysterious idiom is unlike any other ancient written language found in the Middle East, although it seems to share roots with other Anatolian-Indo-European languages.

The sneaky scrawlings start at the end of a cultic ritual text written in Hittite – the oldest known Indo-European tongue – after an introduction that essentially translates to: "From now on, read in the language of the country of Kalašma".

Kalašma is referencing an organized society from the Bronze Age, which probably sat on the northwest fringe of the much larger Hittite Empire in ancient Anatolia – some distance from the capital city of Hattusa, where this clay tablet was later unearthed.

According to Andreas Schachner, head of Hattusa Ruins Archaeological Excavations, the first time he held the tablet, he could feel the weight of its importance.

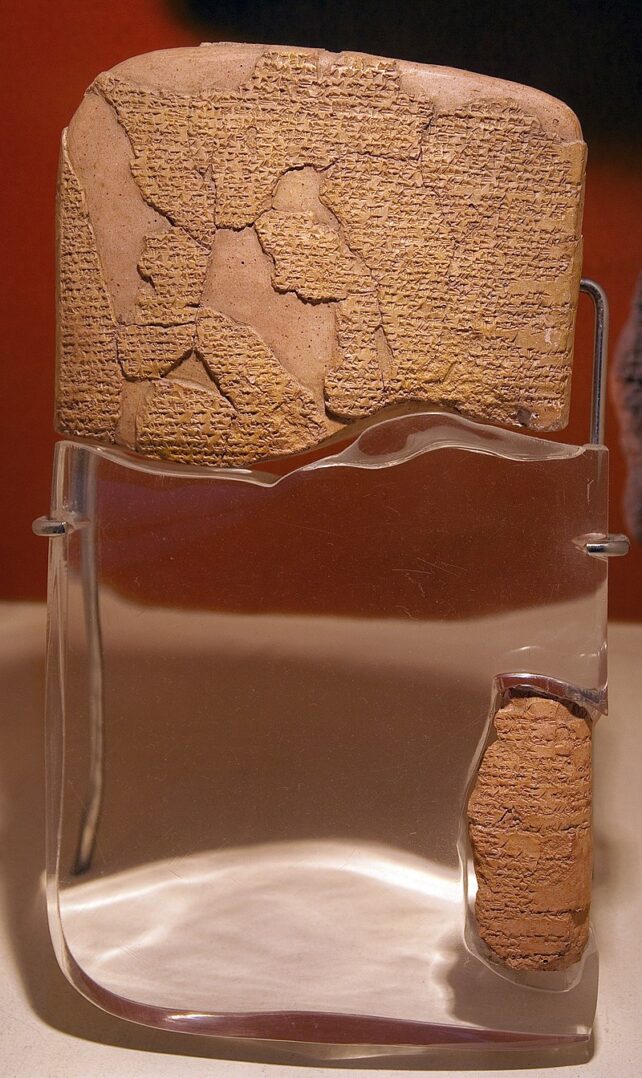

Specifically, he noticed that the clay tablet was remarkably well-preserved compared to more than 25,000 others found at the same site in what is now Boğazköy, Türkiye.

For over a century, historians, archaeologists, and linguists have been working together to uncover and translate Hattusa's incredible archive of royal treaties, political correspondences, and legal and religious texts.

While most of these tablets were written in Hittite cuneiform, experts working at the same site have found other different languages, too. These scripts seem to come from various ethnic groups that once lay in the shadow of the Hittite Empire, during its rule across much of Anatolia from 1650 to 1200 BCE.

The recent discovery of another language is exciting, albeit not too surprising.

"The Hittites were uniquely interested in recording rituals in foreign languages," explains Schwemer.

And not simply for scholarly reasons. The Hittite Empire seems to have celebrated thousands of gods and goddesses. As Hittites conquered more and more land on the large peninsula between the Black and Mediterranean Sea, historians suspect the Empire acquired new religions as a way of bringing fresh subjects into the fold.

By showing respect for other religions, Schachner says the Empire was probably hoping to gain respect during its expansion.

According to the ancient Anatolian historian, Tülin Cengiz, the royal archives of Hattusa mention deities worshiped as far away as Syria and Mesopotamia.

"Embracing these gods with no self pantheon indicates the existence of a tolerance culture," writes Cengiz.

In the ancient Hittite kingdom, it appears to have been the solemn and sole purpose of subjects to worship their divine masters in return for health, food, and happiness.

Scholars suspect the Empire's royal archives were a way to solidify that "state cult" and "provide a detailed picture of the attention required by and accorded to the gods and goddesses".

Borrowing ideas, like cuneiform writing systems, traditions, and religions was probably a way to expand the Empire's reach.

Kalašmans, for instance, ended up fighting for the Hittites against the Egyptian Empire at a battle in 1274 BCE.

Currently, there are no available photos of the newly discovered tablet with Kalašmaic writings, as experts are still working out how to translate it. Schwemer and his colleagues hope to publish their results along with images of their discovery sometime next year.

The world waits with bated breath to see what the tablet has to say.