Climate change has pulled the chair out from underneath the Arctic Ocean's blanket of sea ice.

Once a thick and resilient structure, Arctic sea ice is now thinner and more vulnerable to the seasons than ever before, according to new NASA research.

Combining satellite data and submarine sonars, the study reveals that 70 percent of today's ice cover consists of seasonal ice, the stuff that forms and melts within a single year, instead of thicker, established ice.

While younger sea ice does grow faster, more coverage is not always better. Seasonal sea ice, no matter how extensive, cannot trump the durability of old age and volume.

With a flimsier foundation, Arctic sea ice will find itself increasingly beholden to the whims of the wind and weather. It will also melt far more easily come summertime and especially as global warming continues to heat up our seasons and our oceans.

"The thickness and coverage in the Arctic are now dominated by the growth, melting and deformation of seasonal ice," says lead author and NASA scientist Ron Kwok of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Not all sea ice behaves the same. With every melting season that it survives, the very quality of the Arctic's floating ice pack is altered.

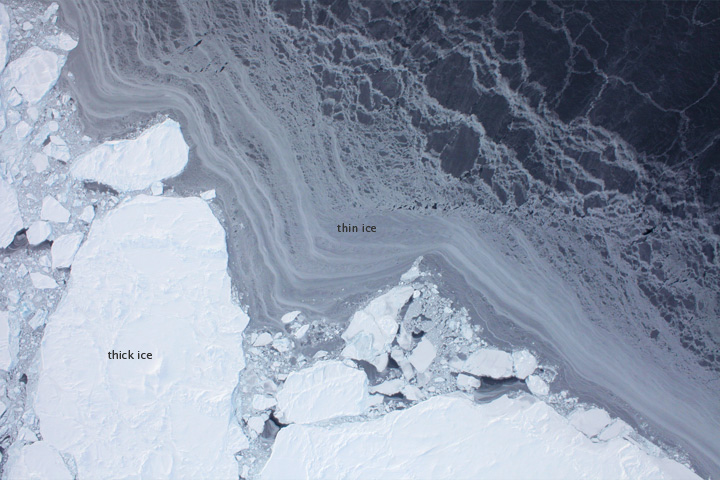

Multiyear ice is the name given to sea ice when it persists more than two years, and its characteristics are quite unique. Unlike young and seasonal sea ice, which is only about two metres (6.6 feet) thick and usually melts come summertime, multiyear ice is thicker, stronger and rougher in nature.

It is also far less saline - so much so that early Arctic explorers used to melt it for drinking water - and the less salt, the less prone to melting.

Modern satellite sensors are now so developed that they can pinpoint these differences from afar.

Since 1958, the study reveals that Arctic ice cover has lost about two-thirds of its thickness, and older ice has shrunk by almost 2 million square kilometres (800,000 square miles).

(NASA Earth Observatory, 2011)

(NASA Earth Observatory, 2011)

Because so much of the older, thicker ice has already melted, Kwok explains that record-breaking changes in ice cover will be less common in the future.

Even now, despite a rapidly warming planet, there has not been a new record sea ice minimum since 2012.

"We've lost so much of the thick ice that changes in thickness are going to be slower due to the different behavior of this ice type," says Kwok.

But just because things are slowing down, does not mean the worst is behind us.

The dramatic shift in volume and quality of Arctic ice cover has left the region even more sensitive to climate change and vulnerable to destruction by shifting local weather patterns.

In 2013, for instance, there was so much seasonal ice that unusually fierce winds were able to push the young ice right up along the coasts, making it thicker there for months.

In the past, Arctic sea ice rarely melted, but now, as temperatures in the north pole are increasing, large amounts of multiyear ice are melting into the ocean every year.

This has shaken up the ratio of multiyear to seasonal ice, placing the region and its ecosystems at risk.

"The combination of thin ice and southerly warm winds helped break up and melt the sea ice in this region," explains Melinda Webster, a sea ice researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

"This opening matters for several reasons. For starters, the newly exposed water absorbs sunlight and warms the ocean, which affects how quickly sea ice will grow in the following autumn.

"It also affects the local ecosystem, such as seal and polar bear populations that rely on thicker, snow-covered sea ice for denning and hunting."

The study has been published in Environmental Research Letters.