Samples of the asteroid Itokawa sent back to Earth from Japan's Hayabusa probe are finally revealing their secrets - including the fact that they're rich in water.

Cosmochemists have analysed tiny fragments in the samples, and for the first time measured the water content within.

They have determined that asteroids like Itokawa bombarding Earth billions of years ago could have brought with them up to half the water in Earth's oceans, which today have a mass of 1.4 × 1021 kilograms.

"We found the samples we examined were enriched in water compared to the average for inner solar system objects," said cosmochemist Ziliang Jin of Arizona State University.

The Hayabusa probe rendezvoused with Itokawa in 2005, collecting mineral samples to fly them home to Earth. These duly arrived in 2010, carefully packaged in a special capsule that protected the samples from the heat of re-entry.

An S-type asteroid composed of siliceous minerals, Itokawa belongs to the second most common type of asteroid in our Solar System, believed to have been broken off from a larger chunk of rock in a collision. It orbits the Sun in the inner region of the main asteroid belt, where siliceous asteroids are the most common.

Since asteroids are relics of the early Solar System, left over from the protoplanetary disc that swirled around a baby Sun, from which the planets formed, they can tell us a lot about the composition of the Solar System when it was still forming.

Something else happened back then, though, according to current theories. It's called the Late Heavy Bombardment, a period of intense bombardment in the early Solar System, in which an incredibly high number of asteroids pelted the inner planets.

These asteroids, scientists believe, brought with them a whooooole bunch of water, which helped shape the planet we know and love today. But it was thought that C-type, or carbonaceous, asteroids were responsible - those that today can be found in the outer regions of the asteroid belt.

But Itokawa's water content remained unexamined, until Jin and his colleague cosmochemist Maitrayee Bose came along.

"Until we proposed it, no one thought to look for water," Bose said. "I'm happy to report that our hunch paid off."

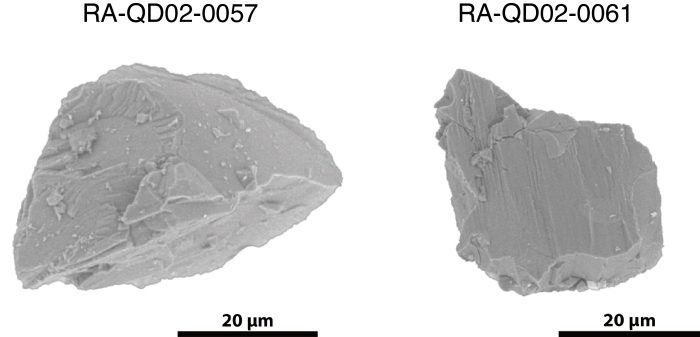

JAXA provided the pair with five precious particles of asteroid. In two of those particles, the pair found pyroxene, a mineral that, on Earth, contains water in its structure. But the extreme conditions of space and the asteroid belt could have removed much, if not all, of that water.

Tiny grains of space. (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), edited by Z. Jin)

Tiny grains of space. (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), edited by Z. Jin)

So the team used the Nanoscale Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometer (NanoSIMS) at Arizona State University to determine how much remained. As it turned out, it was a lot - 698 to 988 parts per million, after correcting for water loss due to impacts and internal processes that would have raised Itokawa's temperature.

That suggests that the asteroid from which Itokawa separated had a water content of 160 to 510 parts per million, the researchers said.

Exactly how Itokawa formed is unknown, but scientists have been able to piece together a likely scenario. They believe it was originally part of an asteroid at least 20 kilometres (12 miles) across, that had at some point been heated between 540 and 815 degrees Celsius (1,100 to 1,500 Fahrenheit).

Either one large collision or several smaller ones broke this parent body into multiple pieces. Two of these pieces fused, and became the peanut-shaped, two-lobed asteroid, about 550 metres (1,800 feet) long. It's been its current size and shape for about 8 million years.

The samples collected by Hayabusa come from a region that is smooth and dusty.

"Although the samples were collected at the surface, we don't know where these grains were in the original parent body," Jin said. "But our best guess is that they were buried more than 100 meters deep within it."

In addition to the water retained in the minerals, the pair found that the minerals themselves have hydrogen isotopic compositions that are indistinguishable from rocks found on Earth, and other inner Solar System bodies. Which means that these bodies likely share a source of water - and that S-type asteroids are instrumental in delivering water and other elements to planets.

"That makes these asteroids high-priority targets for exploration," Bose said.

At the moment, two asteroid missions are ongoing - JAXA's Hayabusa2 is exploring Ryugu, and NASA's OSIRIS-REx is exploring Bennu. Both are carbonaceous asteroids. There are currently no plans for future siliceous asteroid exploration - but maybe this result can change that.

The research has been published in Science Advances.