Astronomers have gazed deep into a distant region of space and found evidence of a hidden trove of young galaxies that are completely unknown to science.

The new observations, made using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile, give us a whole new perspective on the galactic population of a famous region of space called the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field (HUDF).

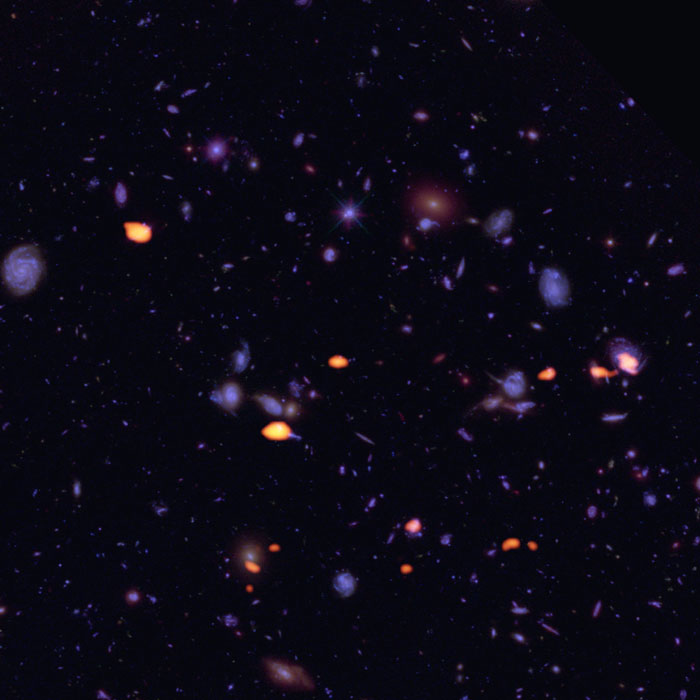

Back in 2004, scientists stunned the world with the HUDF: an image showing a window of space in the Fornax constellation, depicting some 10,000 galaxies as they existed around 13 billion years ago – only shortly after the Big Bang. At the time, this was the deepest, most revealing gaze into the early Universe that humanity had ever witnessed.

And now, several groups of astronomers from around the world have combined their efforts to re-examine this ancient galactic neighbourhood, and discovered the existence of a swathe of baby galaxies within the HUDF that were invisible to the Hubble Space Telescope.

B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF); ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NASA/ESA Hubble

B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF); ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NASA/ESA Hubble

"We conducted the first fully blind, three-dimensional search for cool gas in the early Universe," says astronomer Chris Carilli from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in New Mexico.

"Through this, we discovered a population of galaxies that is not clearly evident in any other deep surveys of the sky."

These discoveries were made possible by ALMA's ability to detect millimetre wavelengths at the end of the electromagnetic spectrum, whereas Hubble only perceives light in the near ultraviolet, visible, and near infrared spectra.

Because of this, ALMA can pick up fainter astronomical objects, especially the cold gas and dust of baby and proto-galaxies – such as massive star-forming clouds and protoplanetary disks – whereas Hubble detects brighter stars and galaxies.

"This is a breakthrough result," says one of the team leaders, Jim Dunlop from the University of Edinburgh in the UK. "For the first time, we are properly connecting the visible and ultraviolet light view of the distant Universe from Hubble and far-infrared/millimetre views of the Universe from ALMA."

ALMA's observations – specifically tailored to pick up on traces of carbon monoxide, a telltale sign of space regions rich in molecular gas and therefore primed for star formation – give us a new and unique perspective on baby galaxies as they looked more than 13 billion years ago.

"We are seeing galaxies of a type never before dreamed of," Carilli told Ria Misra at Gizmodo. "This unique view has revealed a population of galaxies heretofore never seen – galaxies that are very rich in cold gas but have few stars."

When the new observations are laid over the HUDF image of 2004 (as pictured above), we can see how the two surveys complement one another.

Hubble's view of bright galaxies are represented in blue, whereas the orange objects are the carbon monoxide-rich young galaxies in the process of forming.

In short, this is the closest we've ever been to having a complete picture of this distant region of space, and it gives us a greater understanding of the conditions and behaviour of galaxies back when the Universe was very young.

"The new ALMA results imply a rapidly rising gas content in galaxies as we look back further in time," says one of the researchers, Manuel Aravena from the Universidad Diego Portales in Chile.

"This increasing gas content is likely the root cause for the remarkable increase in star formation rates during the peak epoch of galaxy formation, some 10 billion years ago."

Eight papers detailing the findings will be published in upcoming editions of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and The Astrophysical Journal. More information is available here.

Image credit: B. Saxton (NRAO/AUI/NSF); ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); NASA/ESA Hubble