Astronomers have discovered a giant black hole that's so hungry, it's been gorging on a star for more than a decade - more than 10 times longer than any stellar meal detected before.

Not only is this by far the largest meal a black hole has been seen consuming, but the feast has been going on so long that scientists aren't quite sure how it's been sustained without bending the laws of physics. And the answer could tell us how black holes in the early days of the Universe grew more massive than we've been able to explain.

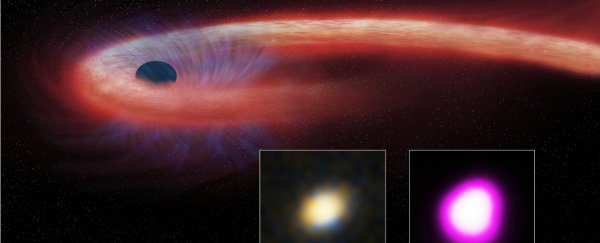

When a star gets too close to a black hole, the black hole's immense gravitational force can rip the star apart - an event known as a tidal disruption event (TDE).

We've seen plenty of these TDE's in the past, thanks to the distinct X-ray flare they produce. After the black hole destroys a star, it flings some of its contents into space at high speeds, and devours the rest, growing larger and blasting out a super hot flare of X-ray radiation in the process.

But most TDEs are short-lived affairs, which is why the new observation is so surprising.

"We have witnessed a star's spectacular and prolonged demise," said lead researcher Dacheng Lin from the University of New Hampshire in Durham.

"Dozens of tidal disruption events have been detected since the 1990s, but none that remained bright for nearly as long as this one."

In fact, that feast has been going on for so long, it's pushing the limits of physics - the star being consumed has consistently surpassed something called the Eddington limit, which is the maximum luminosity a star can achieve before it's no longer stable.

The idea is that if a star is pushing out enough radiation to get this bright, then gravity should barely be able to hold it together. And for that reason we've never really been able to understand how supermassive black holes at the centre of many galaxies, including our Milky Way, grew as big as they are.

This record-breaking hungry black hole is nicknamed XJ1500+0154, and exists at the core of a small galaxy about 1.8 billion light-years away.

It was spotted by a trio of satellites - NASA's Chandra X-ray observatory and Swift satellite, as well as the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton.

The satellites were hunting for TDEs when they stumbled across the incredibly bright flare emitted by XJ1500+0154 back in 2005.

They've been observing it ever since, and although it appears the meal is now winding up, the team's evidence suggests that the black hole was consuming the star's material for well over 10 years.

That means this is either the most massive star we've ever seen get caught up in a TDE, or it's the first time we've seen a smaller star get completely torn apart.

"For most of the time we've been looking at this object, it has been growing rapidly," said one of the researchers, James Guillochon from the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics.

"This tells us something unusual - like a star twice as heavy as our Sun - is being fed into the black hole."

The fact that we now have early evidence that black holes can eat something so massive - and grow so ginormous as a result - opens up a while new world of possibilities when it comes to black holes.

We need to keep in mind that the research has only been published on the pre-print site arXiv.org for the physics community to pore over before it's submitted to a peer-reviewed journal, so we need to wait for independent validation of the results before we get too carried away.

Importantly, if confirmed, this observation could help explain how supermassive black holes were able to get about a billion times more massive than our Sun in the early days of the Universe - something researchers have struggled to explain.

"This event shows that black holes really can grow at extraordinarily high rates," said team member Stefanie Komossa of China's QianNan Normal University for Nationalities.

"This may help understand how precocious black holes came to be."

The team predicts that XJ1500+0154's feeding supply should be greatly reduced in the next decade, causing the black hole to fade in X-ray brightness and disappear from the satellites' view.

Whether or not that happens remains to be seen, but astronomers will be watching the black hole closely.

You can read the full paper here.