Tiny bones locked in stone for millions of years have finally told their sad story.

The 150-million-year-old fossils belong to a pair of pterosaur hatchlings, both of whom appear to have perished in a spectacularly violent weather event, paleontologists have now discovered.

What makes this discovery remarkable isn't just that researchers were able to reconstruct the way they died; it's also that such delicate bones were preserved at all.

Related: Scientists Can Finally Reveal The Secret of How Pterosaurs Took Flight

"Pterosaurs had incredibly lightweight skeletons. Hollow, thin-walled bones are ideal for flight but terrible for fossilization," says paleontologist Rab Smyth of the University of Leicester in the UK.

"The odds of preserving one are already slim and finding a fossil that tells you how the animal died is even rarer."

These two remarkable aspects of the case are actually linked, the researchers found. The conditions present in such violent storms are what created the conditions that led to the preservation of the bones.

There's something really odd about one particular aspect of the pterosaur fossil record. The Upper Jurassic Solnhofen platy limestones of southern Germany have yielded hundreds of individual, but mostly incomplete, pterosaur specimens; a veritable goldmine of data about multiple pterosaur species and their anatomy.

But for some reason, the vast majority of these specimens are of juvenile pterosaurs.

Pterosaurs in general are not well represented in the fossil record because of the fragility of the bones. Yet the bones of juveniles are more fragile than those of adults – so why should they preferentially be preserved in this one location?

Smyth and his colleagues thought that the baby pterosaur pair – both belonging to the Pterodactylus genus, discovered a year apart, and ironically nicknamed Lucky I and Lucky II – might have an answer.

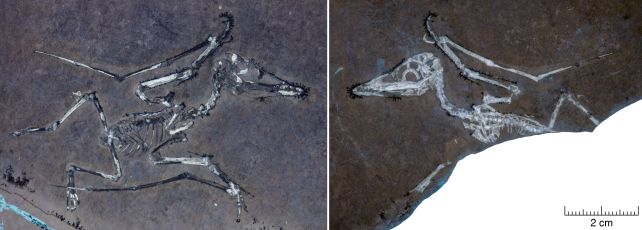

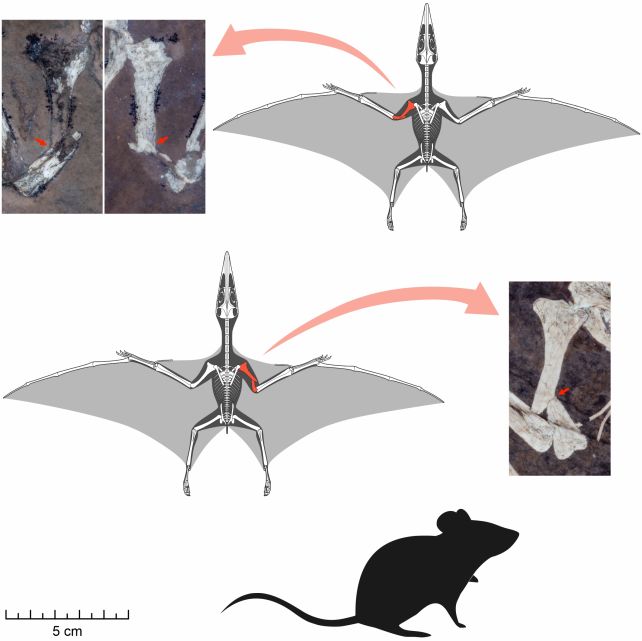

These two tiny individuals, with bodies smaller than a modern mouse, were perfectly preserved, complete, intact, and articulated, thought to be almost unchanged since the day they died.

Both individuals, notably, have broken wing bones, one on the left wing and the other on the right. Both those breaks seem to have occurred in the same unusual way, with a clean, slanted fracture to the humerus, as though the force that broke the bone was applied with a twisting motion. So the researchers put their deerstalker hats on and got to work.

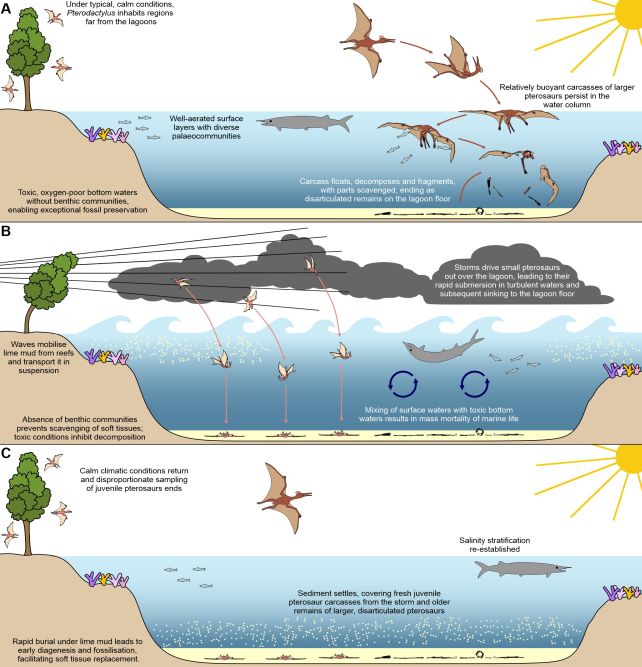

Notably, the Solnhofen limestones were once the silty bed of a saltwater lagoon. According to the team's reconstruction of events, the two tiny pterosaurs met their end in a powerful storm, buffeted by wild winds that broke their wing bones.

These same winds would have then hurled the fragile babies, just a week or two old, into the lagoon waters, choppy and churned up by storm conditions, facilitating sinking to the bottom. There, sediments quickly buried and gradually layered atop their remains, preserving them for eons.

The preponderance of other tiny remains in the fossil bed supports this theory. Older, mature pterosaurs would have been strong enough to withstand and survive the storms that killed their young. Of course, they would have died eventually too, but falling into the water in calm conditions would have seen their carcasses float, disarticulate, and decompose before sinking.

So the vast majority of the pterosaur bones preserved at the bottom of the lagoon would be those of weaker, smaller individuals – a neat resolution to a long-unresolved mystery.

"For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs. But we now know this view is deeply biased," Smyth says.

"Many of these pterosaurs weren't native to the lagoon at all. Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms."

The findings have been published in Current Biology.