The glow-in-the-dark bats you're hanging to decorate for Halloween might be more biologically accurate than you thought. A new study from scientists at the University of Georgia in the US has confirmed that some North American bats glow under UV light.

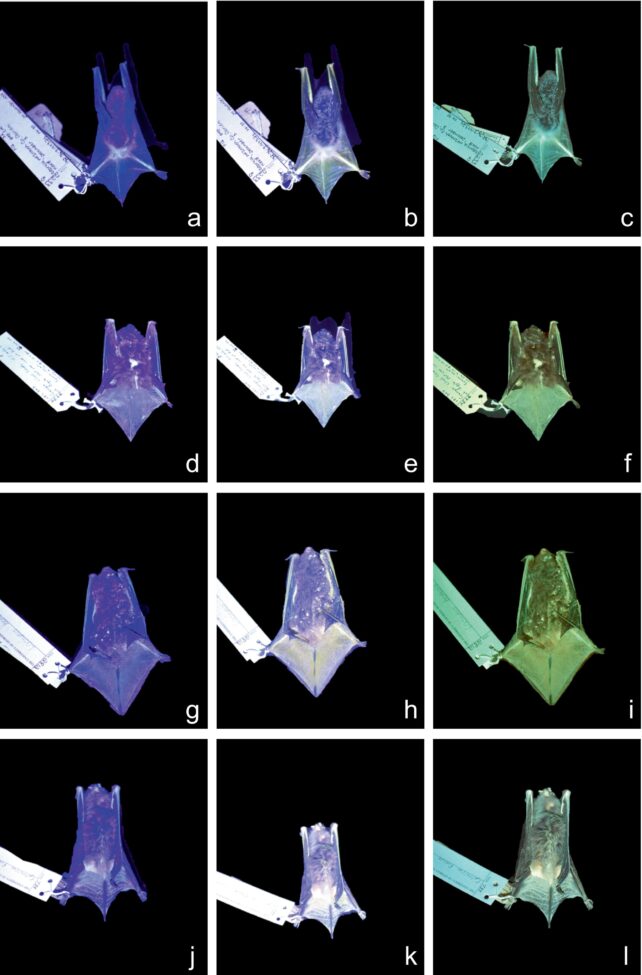

The team examined 60 museum specimens from six species – big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), eastern red bats (Lasiurus borealis), Seminole bats (Lasiurus seminolus), southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius), gray bats (Myotis grisescens), and Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) – and found that every last one of them emitted light after being exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

They're not alone, either: previous studies have found that a whole menagerie of mammals seems to be having a black light party, in a rainbow of colors.

Related: Scientists Shaved Roadkill to Find Out How Mammals Glow in The Dark

But with these bats, there's a curious case of conformity: across all species, sexes, and ages, their photoluminescence was the same. It always came from their wings, hind limbs, and the membrane between their legs, and it was always green, within a narrow range of wavelengths.

According to the researchers, that rules out a few possible explanations for the trait. If everyone's wearing the same shade, it can't be much use for helping bats recognize their own species or to differentiate potential mates from rivals.

"The data suggests that all these species of bats got it from a common ancestor. They didn't come about this independently," says Steven Castleberry, wildlife biologist at the University of Georgia. "It may be an artifact now, since maybe glowing served a function somewhere in the evolutionary past, and it doesn't anymore."

While the wavelengths do fall within the bats' range of vision, the team isn't sure there's even enough light in their environment at night to produce the photoluminescence, especially in their dark roosting spots.

But intriguingly, the locations of the glow, on the wings and lower limbs, are body parts that are visible while bats are flying and foraging. Determining whether this provides a clue to any possible behavioral function will have to wait until researchers can examine live bats.

The research was published in the journal Ecology & Evolution.