While most of us avoid creepy-crawlies at all costs, entomologists – scientists who study insects – need to actively go looking for them.

"My colleague noticed a dead tree in the middle of our university campus," entomologist Adrian Smith from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences told ScienceAlert.

"If you're an entomologist, when you see a tree with that condition, it's always worth peeling off the bark and seeing what you can find under there."

The curiosity has paid off, with the researchers discovering the larvae of a species of lined flat bark beetle (Laemophloeus biguttatus) that has a way of jumping that no-one had documented before.

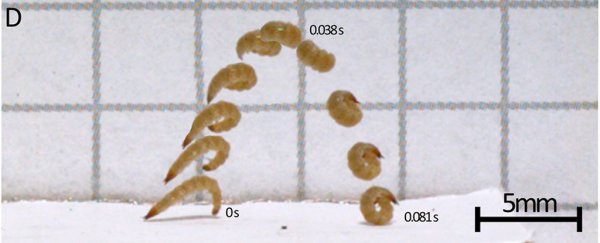

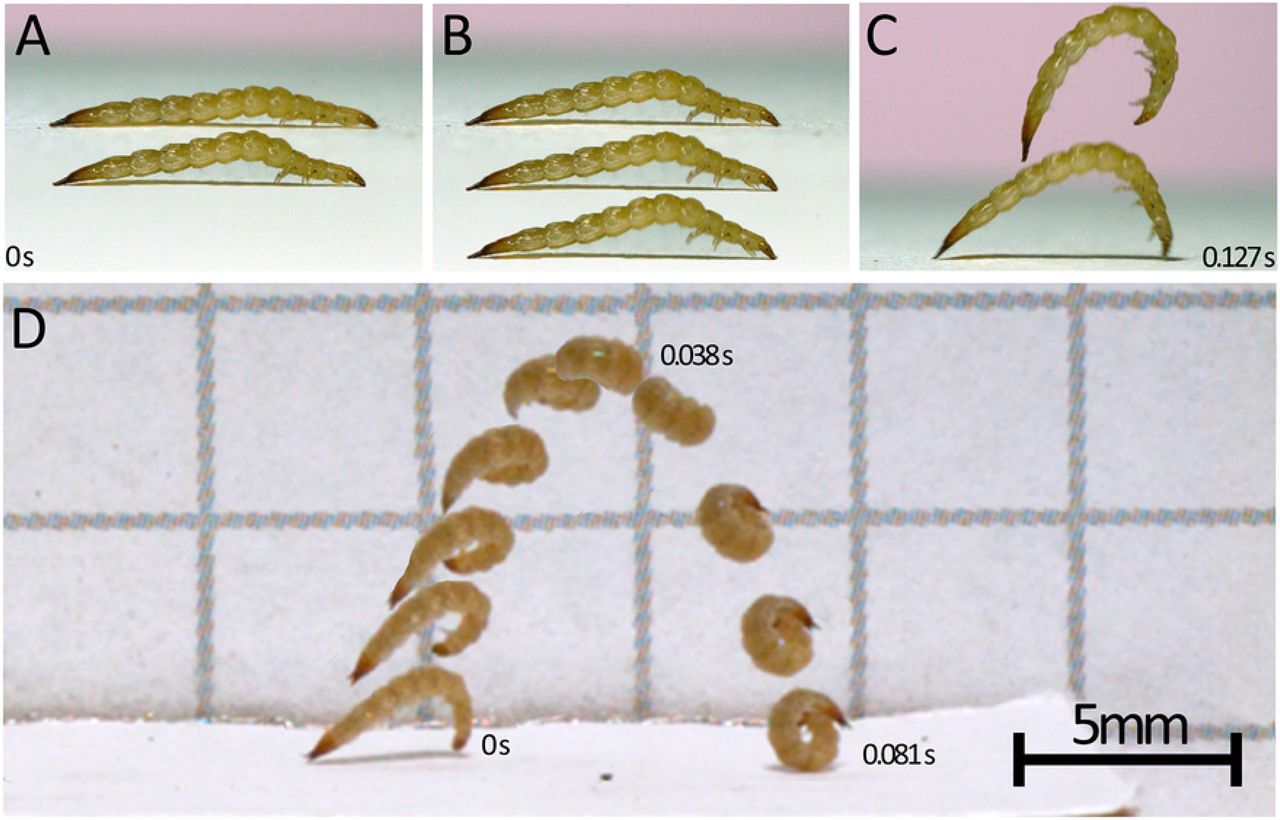

As you can see in the image below, the tiny larvae seem to tighten their bodies before exploding into the air all curled up. The larvae reach take-off velocities of 0.6 meters a second and travel on average two body lengths horizontally and 1.5 body lengths vertically. It's quite a sight to behold.

The larva as it holds and then jumps. (Bertone et al., PLOS ONE, 2022)

The larva as it holds and then jumps. (Bertone et al., PLOS ONE, 2022)

"The way these larvae were jumping was impressive at first, but we didn't immediately understand how unique it was," says entomologist Matt Bertone from North Carolina State University's Plant Disease and Insect Clinic, the first author of a new paper on the discovery.

"We then shared it with a number of beetle experts around the country, and none of them had seen the jumping behavior before. That's when we realized we needed to take a closer look at just how the larva was doing what it was doing."

Most beetles or jumping insects use a latch mechanism to be able to aid their powerful spring – the 'explosion' is powered by that latch releasing. You can see this type of biological mechanism in action in the powerful spring loaded 'punch' of a mantis shrimp.

But in this case the researchers weren't able to find a latch, and it's not like they didn't give it a red-hot go. They used cameras that can capture 60,000 frames a second, as well as MicroCT scans and scanning electron microscope imaging to look over the whole body in detail, but nothing could be found.

The team even looked at the larva's body composition to determine if they could jump that high just using their muscles, without a latch mechanism. They discovered that the tiny creature didn't have enough muscles to pull it off.

"We know that they are storing energy, but 'where' is a different question," says Smith.

"Their little beetle claws lose grip of the ground, and then all of a sudden it's like a cascade."

The researchers have shown that instead of using a latch, the larvae tense up their whole bodies, and when they lose footing on one of their legs, their head is able to curl inwards and launch them into their mighty jump. The jump itself, which you can see in Smith's video below, is surprisingly beautiful.

Although the team aren't sure why the larva jumps as it does, living in a temporary home under the bark of a dead tree means you need to be able to evacuate quickly.

"It might be to escape predators, it might be to disperse themselves, it might be a combination," says Smith.

"I would work on it more but we haven't seen them since."

Unfortunately, this insect-filled tree is gone from the North Carolina State University campus now. The researchers only had a small amount of time to collect as many bugs as they could before the tree ended up in the woodchipper.

But all is not lost. When Smith put up a different video on his YouTube channel about jumping maggots, he included a little aside about the jumping larvae. A researcher in Japan named Takahiro Yoshida saw the video, and instantly realized that he'd seen another type of beetle larvae local to his area jumping in a similar way.

This second beetle is in the same taxonomic family, but is a different genus, so they are only distantly related.

"He noticed [these larvae] doing a really rapid jump behavior, so he filmed them with his cell phone at the time. He probably didn't think any more about it until he saw that video and he's like, 'I know exactly what that is. I have this cool thing, let me email these people immediately!'" says Smith.

"So, it's probably a widely dispersed behavior in this group of animals that wasn't known before."

Despite the ick factor, maybe we should all be spending more time looking under bark. Who knows, you might even get lucky and have a beetle larva jump at you.

The research has been published in PLOS ONE.