The blue shark (Prionace glauca) might be more than its name. Scientists investigating the sleek ocean predator's skin discovered nanostructures that not only produce its signature hue, but also potentially let it change color like a chameleon.

Animals produce their colors in various ways. Some rely on pigmented cells that reflect a color by selectively removing wavelengths from ambient light, while others have microscopic light-scattering structures that build or remove select wavelengths – think peacock feathers.

A rare few can tweak their color-coding features in response to their surroundings, by modifying how wavelengths are absorbed or scattered.

Now it's been revealed that the blue shark has that color-morphing ability, in a new study led by scientists at the City University of Hong Kong (CityU).

Related: Squids' Amazing Color Shifting Could Be Key to Hyper-Efficient Solar Tech

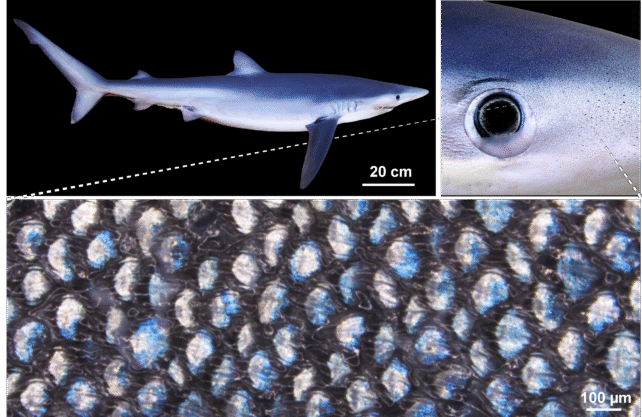

As their name suggests, blue sharks generally have dark blue coloration on their backs and lighter bellies. Their skin is lined with tooth-like scales called dermal denticles, and inside these are pulp cavities that play a key role in producing color.

The researchers examined these denticles using optical and electron microscopy, spectroscopy, and other imaging technology. They found that the pulp cavities contain guanine crystals, which reflect blue light, and tiny little sacs of the pigment melanin that absorb other colors.

"These components are packed into separate cells, reminiscent of bags filled with mirrors and bags with black absorbers, but kept in close association so they work together," says Viktoriia Kamska, molecular biologist at CityU.

On closer inspection, the team found that these structures don't just put the "blue" in blue shark – they could potentially respond to the animals' environment to change their colors. Narrow spacing between layers of guanine crystals gives the sharks the blues, but if those spaces widen, they can potentially turn shark skin green or yellow.

Chameleons also get their color-changing abilities by shuffling guanine crystals around. In the shark's case, this could naturally boost their camouflaging capabilities. If they dive deeper, for instance, the greater water pressure should push the crystal layers closer together, darkening their skin to match the darker waters.

"What's fascinating is that we can observe tiny changes in the cells containing the crystals and see and model how they influence the colour of the whole organism," says marine biologist Mason Dean, head of the CityU lab behind the discovery.

At this stage, the effects have only been simulated, but the team plans to study how the mechanism might function in the natural environment of wild sharks, to gain a deeper understanding of how nature engineers color at the nanoscale.

The research was presented at the Society for Experimental Biology Annual Conference in Belgium.