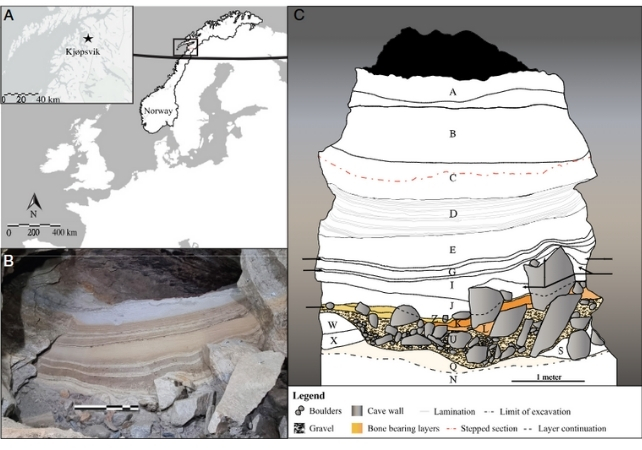

For 75,000 years, the remnants of a diverse ecosystem of Ice Age animals have lain hidden in the shelter of Arne Qvam Cave in Norway.

Scientists have only just begun to grasp the full scope of its contents, which are the oldest evidence we have describing the diversity of animals that flourished in one of the glacial period's warmer stints.

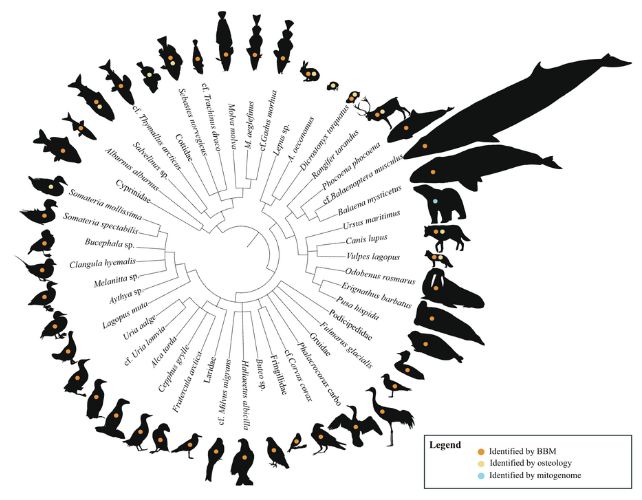

This rare and remarkably extensive archive of ancient Arctic fauna covers a wide spectrum of vertebrates, from small mammals like the collared lemmings (Dicrostonyx torquatus) and voles (Alexandromys oeconomus) that scurried across the tundra, marine and freshwater fish, and more than 20 bird species, to the landscape's largest marine mammals, like whales, walruses, and even a polar bear.

Related link: Oldest Human DNA in UK Reveals Ancient Peoples Emerging From The Ice Age

"We have very little evidence of what Arctic life was like in this period because of the lack of preserved remains over 10,000 years old," says evolutionary biologist Sanne Boessenkool of the University of Oslo.

This find fills a "significant void in our understanding of biodiversity and the environment during a period of dramatic climate change," Boessenkool and team write in their paper describing the finds.

The cave was concealed within a mountain until the 1990s, when a tunnel built for mining exposed the secret chamber. Even then, large excavations were not carried out until 2021 and 2022, when the animal remains emerged from the lower layers of sedimentary rock.

The collared lemmings were a particularly exciting find: this species is now extinct in Europe, and until now, the only signs they had ever lived there were from Scandinavia.

The remains of freshwater fish suggest there were lakes and rivers in the tundra environment, while bowhead whales and walruses would have required sea ice. This probably wasn't present year-round, however, because the harbour porpoises also found in the cave avoid waters that have frozen over.

These animals were living in a period of global cooling. The entire ecosystem seems to have depended on melting glaciers that provided fresh water and exposed the ocean; once the landscape froze over once again, the biodiversity disappeared, suggesting the mix of animals were unable to migrate or adapt to the colder, drier environment.

"This highlights how cold adapted species struggle to adapt to major climatic events. This has a direct link to the challenges they are facing in the Arctic today as the climate warms at a rapid pace," lead author and Bournemouth University zooarchaeologist Sam Walker says.

"The habitats these animals in the region live in today are much more fractured than 75,000 years ago, so it is even harder for animal populations to move and adapt."

While many of these kinds of animals can still be found in the Arctic today, they no longer live in the cave's vicinity. When the researchers compared the bones' mitochondrial DNA with those of extant populations, they found none of the ancient lineages had survived when the glaciers froze up again.

But, as Boessenkool points out, "this was a shift to a colder [climate], not a period of warming that we are facing today.

"And these are cold-adapted species – so if they struggled to cope with colder periods in the past, it will be even harder for these species to adapt to a warming climate," she says.

This research was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.