Winter got off to a fast start in the Lower 48 even before it was technically winter. Waves of cold gripped the eastern two-thirds of the United States and several winter storms tracked across the region.

Conditions have since eased some, but the heart of winter lies ahead. Will cold and snowy conditions return and turn more harsh?

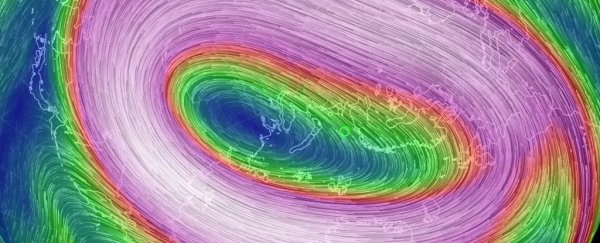

The polar vortex, the roaring river of air winding around the North Pole, holds the cards. What they reveal could be very disturbing and a harbinger of extreme winter weather in the Eastern United States.

Judah Cohen, a climate researcher at Atmospheric and Environmental Research, monitors the condition of the vortex, every day checking the latest prediction models for any sign of disturbance. He is concerned about what some models are projecting at the end of December or early January.

When the vortex, perched some 60,000 feet (18 kilometres) high in the atmosphere, is stable, winter conditions over the United States and Europe tend to be rather ordinary. Winter is still winter, with the normal mix of storms, cold snaps and thaws.

But when the vortex is disrupted, an ordinary winter can suddenly turn severe and memorable for an extended duration. "[It] can affect the entire winter," Cohen said in an interview.

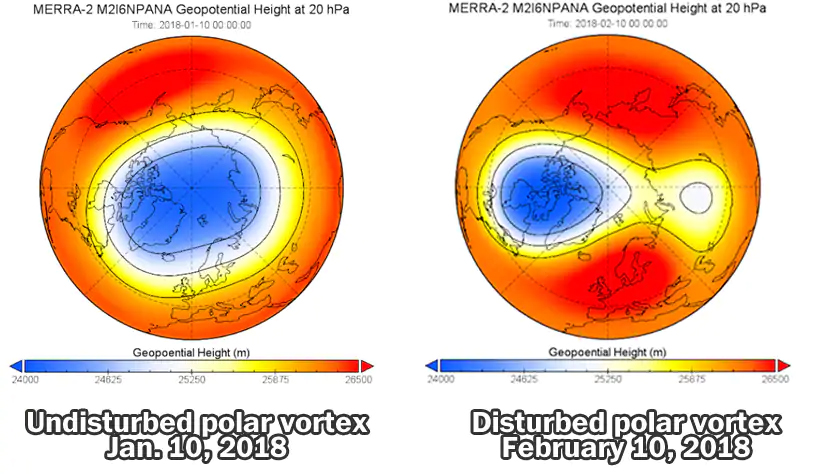

Rewind to February of last year to understand the implications. Up to that point, the vortex had held in its stable state, and the winter was a mild, unremarkable one. But then, abruptly, the vortex split.

The fracture set off a chain reaction, which first unleashed a punishing blast of cold in Europe and Asia. The media dubbed the cold snap the "beast from the east" as frigid Siberian air flooded the continent.

Then, the piercing cold hit the Lower 48 states in March. It triggered four consecutive nor'easters along the East Coast, where the polar air collided with the relatively mild Atlantic waters.

The 4 nor'easters of March 2018 and we were so close to having a fifth! More info: https://t.co/jXT9weSt4K pic.twitter.com/a4sEzMqcOu

— Capital Weather Gang (@capitalweather) March 27, 2018

Its effects lasted weeks. "We were still feeling the impacts into the end of April," Cohen said.

Similar polar vortex disruptions defined the character of several other extreme winters, including 2009-2010, the snowiest on record in parts of the Mid-Atlantic, and 2013-2014, which was abnormally cold, especially in the Great Lakes.

Predicting the next polar vortex disruption

Cohen shares insights on the state of the polar vortex on his blog and Twitter feed. Last week, he tweeted: "Confidence is growing in a significant #PolarVortex disruption in the coming weeks. This could be the single most important determinant of the weather this #winter across the Northern Hemisphere."

But the vortex behavior can be fickle and is difficult to predict. The American modeling system favors a disruption this month, while the European modeling system delays it until early January.

Vortex disruption is associated with a phenomenon known as a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event. The stratosphere is the layer of air in which the vortex resides, above the troposphere, where most weather occurs (there is also a tropospheric polar vortex, which is at times linked to the vortex in the stratosphere).

During such a stratospheric warming event, the prevailing winds decrease or even change direction, the layer warms, and the vortex is displaced and sometimes splits apart.

(NASA, adapted by CWG)

(NASA, adapted by CWG)

Forecasting stratospheric warming events is still a young science, and model predictions aren't always that reliable. In this case, confidence is boosted somewhat by the fact that every simulation in the American modeling system projects stratospheric warming within the next 16 days.

But Amy Butler, a scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, tweeted "not all other models on board yet so still reason to be cautious."

Assuming the stratosphere warms and vortex disruption occurs, it takes time for changes high up in the stratosphere to work their way down through the atmosphere and affect day-to-day weather.

The chain of events spurred by the disruption begins with an easterly flow of air descending from the stratosphere to the troposphere. The jet stream, the air current about 30,000 feet (9 kilometres) high in the troposphere, weakens in response and is forced south.

As the jet stream shifts south, cold air evacuates the polar regions, like a refrigerator door left open, and spills into the mid-latitudes.

Where the cold air spilling out of the Arctic will first land, whether Europe, Asia, or the continental United States, is difficult to predict. In many past vortex disruptions, the cold has first hit the eastern hemisphere. It may do so again this time.

Jason Furtado, a professor of meteorology at the University of Oklahoma, tweeted that "it will be felt first in Eurasia" based on model forecasts. This means the Lower 48 states may be weeks away from feeling any effect.

Immediate effects of the forecasted major polar vortex breakdown will be felt first in Eurasia, as past events indicate. This also makes sense with a shift in the polar vortex axis towards the Eastern Hemisphere. pic.twitter.com/WOjzK7sCAk

— Jason Furtado (@wxjay) December 17, 2018

There's some chance that the disruption fails to materialize or is further delayed. Its timing has been pushed back in some model forecasts, and the more its effects are kicked down the road, the less impact it would potentially have on the core winter months.

"The longer it takes to happen, the bigger chance we have of a warmer winter," Cohen said.

Using the polar vortex to predict an entire winter?

As noted, polar vortex behavior is difficult to predict even one to two weeks into the future. But Cohen says the likelihood of a disruption any given winter can be predicted up to months ahead of time by analyzing the behavior of snow cover in Siberia and the amount of sea ice in the Arctic.

When the snow advances quickly in the fall over Siberia and sea ice extent is below normal in the Barents-Kara sea, historical data suggests the vortex has an increased chance of being disrupted come winter, Cohen said. This past fall, both conditions were satisfied, leading him to conclude that "everything seems to be in place for a significant disruption."

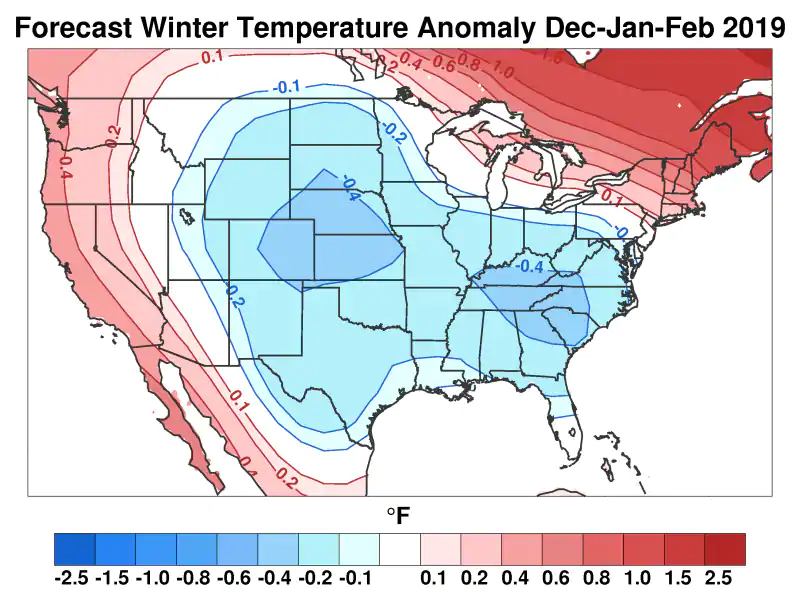

Accordingly, Cohen's winter outlook leans toward colder than normal conditions in the Central and Eastern United States. He's also predicting above-normal snowfall in Washington; 21 inches, compared to the average of around 15 inches.

Judah Cohen's winter temperature difference from normal outlook. (Judah Cohen, AER)

Judah Cohen's winter temperature difference from normal outlook. (Judah Cohen, AER)

Cohen, who has prepared winter outlooks for more than a decade, has shifted his methodology based on his growing appreciation of the importance of vortex behavior and how a disruption can fundamentally change the character of a winter.

He previously used Siberian snow cover in October to attempt to predict the winter phase of a pattern known as the Arctic Oscillation. He had found a relationship between rapidly advancing snow cover and the oscillation's negative phase, which favored cold, snowy conditions in eastern North America.

But in the winters of 2014-15 and 2015-16, the relationship between snow cover and the oscillation failed, he said, so his methodology "needed refinement."

Since then, he has evolved his methodology to key in on the polar vortex (which is related to the phase of the Arctic Oscillation but not dependent on it), which "can give you a better forecast than the phase of the Arctic Oscillation."

Cohen's methodology may provide clues about vortex behavior not just months but years into the future, since it is linked to Arctic Sea ice extent, which is in decline.

As climate warming continues to shrink sea ice in the Barents-Kara sea region in coming years, "that will tend to increase polar vortex disruption," he said. In other words, the continental United States, Europe and Asia may face a future of wild winters.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.