Significant brain defects known as Chiari malformations could be down to the genes some of us have inherited from Neanderthals, according to a new study, causing a mismatch between brain shape and skull shape.

The study focuses on Chiari malformation type I (CM-I), where the lower part of the brain extends too far into the spinal cord – typically linked to having a smaller-than-normal occipital bone at the back of the skull. It can lead to headaches, neck pain, and more serious conditions, and is thought to affect up to 1 in 100 people.

Several other ancient human species had different skull shapes to our own, and a previous study published in 2013 put forward the idea that interbreeding between Homo sapiens and these other hominins may be a root cause of Chiari malformation type I (CM-I), the mildest type of the group.

Related: What Really Killed The Neanderthals? A Space Physicist Has a Radical Idea

Now, a team led by osteoarchaeologist Kimberly Plomp from the University of the Philippines has tested this hypothesis. "The legacy of these interbreeding events can be identified in the genomes of many living humans," the researchers write.

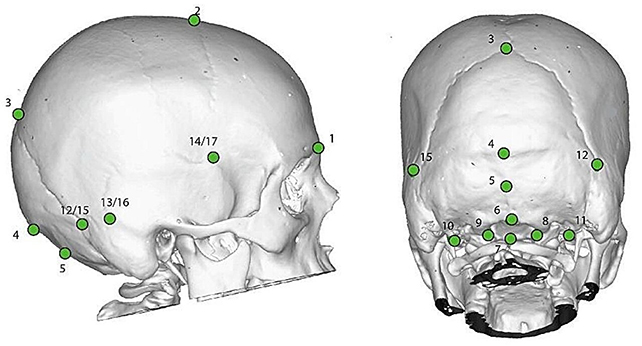

The researchers used 3D modeling and shape analysis techniques to compare 103 skulls of people today with and without CM-I, and 8 fossil skulls from ancient species, including Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, and Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals).

People with CM-I had differences in skull shape, the analysis showed, including the area where the brain connects to the spine. However, these skull shapes weren't similar to all of the ancient hominins studied – only to Neanderthals.

In fact, skulls from H. erectus and H. heidelbergensis were more similar to the skulls of modern humans without CM-I. As a result, the researchers suggest the original hypothesis was too broad, and should be adapted to look specifically at Neanderthal links.

"Rather than the genes being traceable to H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, and H. neanderthalensis, our results are consistent with them being traceable just to H. neanderthalensis," write the researchers.

The study team proposes a Neanderthal Introgression Hypothesis to replace the one formed in 2013. It adds to a growing body of evidence around how early Homo sapiens and Neanderthals mingled, interbreeded, and exchanged genetic information.

Next, the researchers are keen to expand the sample used in their analysis – in terms of both modern and ancient skulls, and across ages – which should tell us more about the relationship between CM-I skull structures and skulls in these early peoples.

The hypothesis also needs to be put to the test in groups of people from different parts of the world. We know that African populations have less Neanderthal DNA than populations in Europe and Asia, which should be reflected in cases of CM-I.

Ultimately, these findings and the techniques used to reach them could help inform ways of treating Chiari malformations or perhaps stopping them from happening in the first place – although it's likely there are several causes for the condition, including genetics.

"The methods would seem to have the potential to help us develop a deeper understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of Chiari malformations, which could in turn strengthen diagnosis and treatment of the condition," write the researchers.

The research has been published in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.