An injectable "vaccine" delivered directly to tumours in mice has been found to eliminate all traces of those tumours, cancer researchers have found - and it works on many different kinds of cancers, including untreated metastases in the same animal.

Scientists at Stanford University School of Medicine have developed the potential treatment using two agents that boost the body's immune system, and a human clinical trial in lymphoma patients is currently underway.

"When we use these two agents together, we see the elimination of tumours all over the body," said senior researcher, oncologist Ronald Levy.

"This approach bypasses the need to identify tumour-specific immune targets and doesn't require wholesale activation of the immune system or customisation of a patient's immune cells."

Cancer immunotherapy is tricky. Because cancer cells are produced by the body, the immune system doesn't see them as a threat the same way it sees invaders like viruses.

That's why some cancer immunotherapy treatments focus on training the immune system to recognise cancer cells as a problem.

It's an effective area of treatment, but one that often involves removing the patient's immune cells from their body, genetically engineering them to attack cancer, and injecting them back in - a process that is both expensive and time-consuming.

The Stanford vaccine could be much cheaper and easier.

It doesn't work like the vaccines you might be familiar with. Instead of a prophylactic administered prior to infection, the researchers gave it to mice that already had tumours, injecting directly into one of the affected sites.

"Our approach uses a one-time application of very small amounts of two agents to stimulate the immune cells only within the tumour itself," Levy said.

"In the mice, we saw amazing, bodywide effects, including the elimination of tumours all over the animal."

The vaccine exploits a peculiarity of the immune system. As a tumour grows, the immune system's cells, including T cells, recognise the cancer cells' abnormal proteins and move in to take care of business.

But cancer cells can accumulate mutations to avoid destruction by the immune system, and suppress the T cells, which attack abnormal cells.

The new vaccine works by reactivating these T cells.

It combines two key agents. The first is a short piece of DNA called CpG oligonucleotide. This, together with other nearby immune cells, amplifies the expression of an activating receptor on T cells called OX40, which is a member of tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily.

The second agent is an antibody that binds to OX40, activating the T cells to fight cancer cells.

These two agents are injected together in microgram amounts directly into the tumour. This means that they only activate T cells inside the tumour, ones that have already recognised cancer cells as a threat.

These cells get to work on the tumour, but some of the T cells then leave the site of the tumour to find and destroy other tumours in the body.

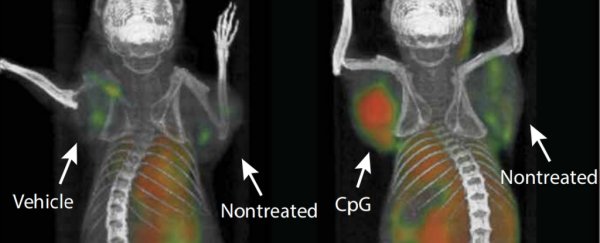

To test it, laboratory mice were transplanted with mouse lymphoma in two places, or genetically engineered to develop breast cancer.

Of the 90 mice with lymphoma, 87 were completely cured - the treatment was injected into one tumour, and both were destroyed. The remaining 3 had a recurrence of the lymphoma, which cleared up after a second treatment.

The treatment was also effective on the mice genetically engineered to develop breast cancer. Treating the first tumour often, but not always, prevented the recurrence of tumours, and increased the animals' lifespan, the researchers said.

The team then tested mice with both lymphoma and colon cancer, injecting only the lymphoma. The lymphoma was destroyed, but the colon cancer was not. This demonstrates that T cells in tumours are specific to that kind of tumour - so the treatment isn't without limitations.

But it does mean that immunotherapy is possible without genetically engineering cells outside the body; or, as is the case with a previous vaccine, extracting cancer RNA, treating it, injecting it into the body, and applying an electric charge to deliver it to immune cells.

Its efficacy is about to be tested, though. The clinical trial currently underway is expected to recruit 15 patients with low-grade lymphoma to see if the treatment works on humans.

If it's effective, the treatment may be used in the future on tumours before they're surgically extracted to help prevent metastases, or even prevent recurrences of the cancer.

"I don't think there's a limit to the type of tumour we could potentially treat, as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system," Levy said.

The research has been published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

This article was originally published in February 2018.