The earliest cities in Europe were built on the foundations of a mostly vegetarian diet, according to new research. The findings suggest that even with the dawn of agriculture and large, planned settlements, meat was but a delicacy.

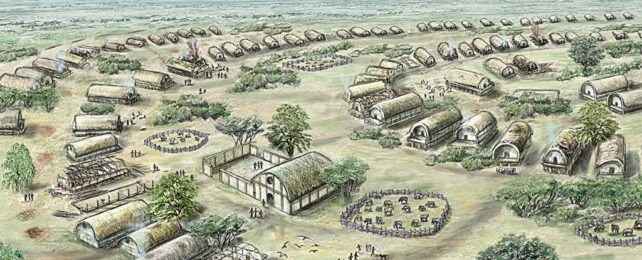

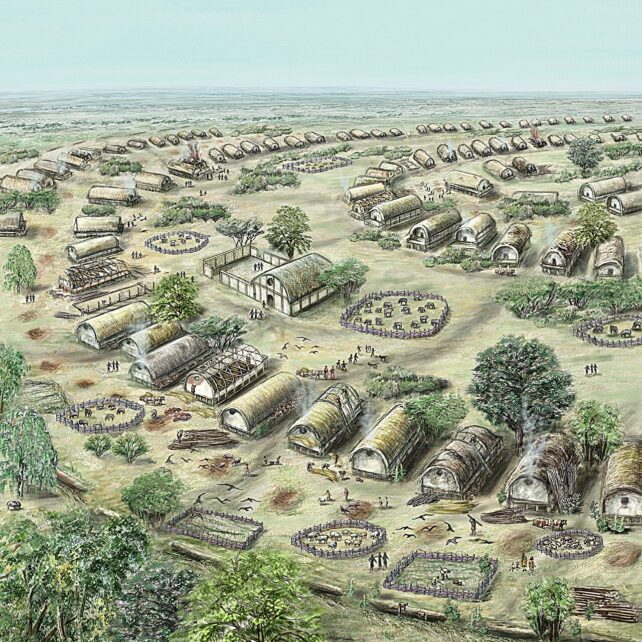

The gigantic circular cities of the Trypillia culture emerged around 6,000 years ago in what is now Ukraine and Moldova.

The largest of these mega sites covered an area equivalent to several hundred football fields of land and once housed up to 15,000 people. They were larger than any other settlements in the world at the time, rivaling even the cities of ancient Mesopotamia that would soon follow in the Fertile Crescent.

Feeding each and every mouth in Trypillia society required "extremely sophisticated food and pasture management," says paleoecologist Frank Schlütz, who led the study at the Christian-Albrechts-University in Germany.

But even though cattle were a crucial part of the system, beef wasn't.

Between 4200 and 3650 BCE, animals domesticated by Trypillia societies were prized largely for their poop, not their flesh, according to Schlütz and his team.

An analysis of nitrogen isotopes in teeth, bones, and soil from the remains of Tryphillia societies suggests that early farmers in Europe were mostly consuming peas, lentils, and cereal grains, like barley.

Cattle, sheep, and goats, which were kept in fenced pastures, were largely used to fertilize farmland. These animals also ate peas and grains, and their manure boosted the production of later crops.

Slaughtering the herds for meat would have depleted a vital resource after much labor raising them, collapsing the whole system.

Previously, some scientists had assumed there was intensive meat production in Trypillia societies, based on the estimated size of their herds. But that may not be true after all.

Animal products contributed just 8 to 10 percent of the regular Trypillia diet, according to Schlütz and his team.

"We hypothesize that there would have been days during which only meat was consumed," the authors write, as well as "some everyday meat consumption, preferably from small animals".

When crops and soil are fertilized by manure, biological turnover is increased, resulting in higher nitrogen isotope levels overall.

This is how scientists determined that the crop yields of pea seeds and broad beans, found in the soil of Trypillia sites, were probably improved with "high levels of manuring, over long periods, on small plots close to houses and stables."

In its heyday, Trypillia culture was one of a kind. Its settlements, which dot Ukraine and Moldova to this day, were designed in concentric circles, with rows of houses lined up along 'ring corridors', encircling an open central place.

The largest mega-sites of Trypillia show unusually high nitrogen isotope values compared to smaller sites, indicating "sophisticated dung management."

Cattle dung appears to have been the main fertilizer. Researchers predict hundreds of cows were "extensively pastured" at mega-sites, sometimes quite far from the settlement itself.

Sheep and goats were also pastured, albeit to a smaller extent.

The whole system was self-sustaining. Some mega sites were settled for over 150 years, providing a stable home for several generations of farmers.

The "wise management of nutrients" meant that Trypillia societies did not overexploit their natural resources, the researchers say.

No one really knows why the Trypillia culture dispersed into obscurity around 3000 BCE. Some experts suspect it was destroyed by force, or as the result of political tensions. Others hypothesize it was a colder and drier climate that spelled the end for these once flourishing societies.

The discovery of such an advanced agricultural technology that didn't exploit the natural environment makes it all the more likely that the demise of the Trypillia was not economic, but based on social or political changes.

It seems even a sustainable and nutritious veggie-based diet can't protect from all the woes of human society.

"As we know from previous studies, social tensions arose as a result of increasing social inequality," says archaeologist Robert Hofmann, also from the Christian-Albrechts-University in Germany.

"People turned their backs on large settlements and decided to live in smaller settlements again."

The study was published in PNAS.