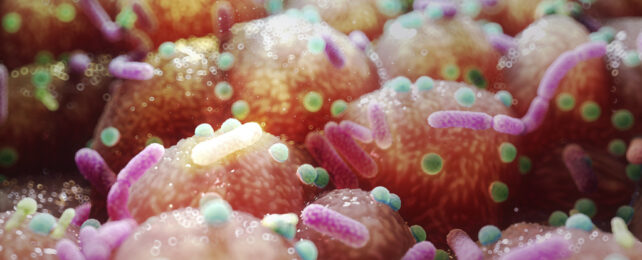

Microbes living in our guts ooze a substance that could help protect us against excessive weight gain, according to observations in mice.

The bacteria-derived compound may explain why early exposure to antibiotics can play a role in childhood obesity, a condition which is rising globally.

Vanderbilt University biochemist Catherine Shelton and colleagues discovered this by giving young mice a high or low fat diet, with or without exposure to antibiotics. Mice only given penicillin antibiotics did not gain weight, but those also on a high fat diet did.

By sampling the abundance of gut bacteria within these lab animals the team were able to identify a drop in Lactobacillus bacteria in the weight-gaining mice that were exposed to antibiotics.

Past research linked disturbances in the gut microbiome to a decrease in a regulatory protein PPAR-γ2, known to be involved in fat processing in intestines. Shelton and team saw the same decrease in mouse cells that line their intestines. This could be reversed when the cells were inoculated with Lactobacillus, which allowed them to identify a molecule produced by the bacteria called phenyllactic acid.

The compound interacts with the PPAR-y2 receptor in the gut cells that plays a role in the transfer of lipids from the digestive tract. The team demonstrated that phenyllactic acid did indeed block fat secretion in intestinal epithelial cells.

"The lack of this one microbe and its metabolite alters the way that intestinal epithelial cells package fat, so that the cells put more fat into the circulation," explains Vanderbilt University microbiologist Mariana Byndloss.

"Phenyllactic acid is a metabolite that normally tells the epithelial cells not to package and secrete as much fat. When the epithelial cells lose that signal from the microbiota, they start to behave differently, and the mice get fatter."

So the researchers gave young mice phenyllactic acid and, sure enough, it protected them from the metabolic dysfunction caused by the combination of early exposure to antibiotics and a high fat diet.

"Multiple bacterial species produce phenyllactic acid, including species belonging to the Bifidobacteriaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae families," Shelton and team write in their paper.

"Interestingly, we see a depletion of Bifidobacteriaceae and Peptostreptococcaceae in mice fed a high fat diet and mice exposed to a high fat diet and antibiotics, suggesting that multiple bacterial species may contribute to phenyllactic acid production in the intestine."

The researchers have yet to confirm this mechanism is the same in young humans, but we share the same components. In fact, baby poop is known to contain phenyllactic acid levels that change with the abundance of Bifidobacterium.

Lactobacillus are the bacteria commonly used in probiotics and found in fermented foods like kimchi and kombucha.

"Some cultures encourage their kids to drink fermented milk, so they may already be unintentionally providing this protective 'therapeutic' to their children," says Byndloss.

Along with probiotics, maintaining a healthy, low fat diet may help mitigate the impact of antibiotics on young human microbiomes, the researchers suspect.

Their work was published in Cell Host & Microbe.