Scientists have been doing some great work when it comes to peering back through billions of years to figure out what ancient Earth would have looked like, and a new study reveals that the earliest conditions on our planet were probably even more hostile than originally imagined.

In particular, researchers now think that we've underestimated the levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the Sun that reached the surface of Earth – and that these levels could have been up to 10 times higher than previously thought during certain periods.

The focus of the research is on the last 2.4 billion years of history, since the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) when oxygen levels in the atmosphere and oceans first started rising from virtually nothing. Not only do the new findings teach us more about Earth's history, they could improve our understanding of the atmospheres on other planets too.

"We know that UV radiation can have disastrous effects if life is exposed to too much," says astrophysicist Gregory Cooke, from the University of Leeds in the UK. "For example, it can cause skin cancer in humans. Some organisms have effective defense mechanisms, and many can repair some of the damage UV radiation causes."

"Whilst elevated amounts of UV radiation would not prevent life's emergence or evolution, it could have acted as a selection pressure, with organisms better able to cope with greater amounts of UV radiation receiving an advantage."

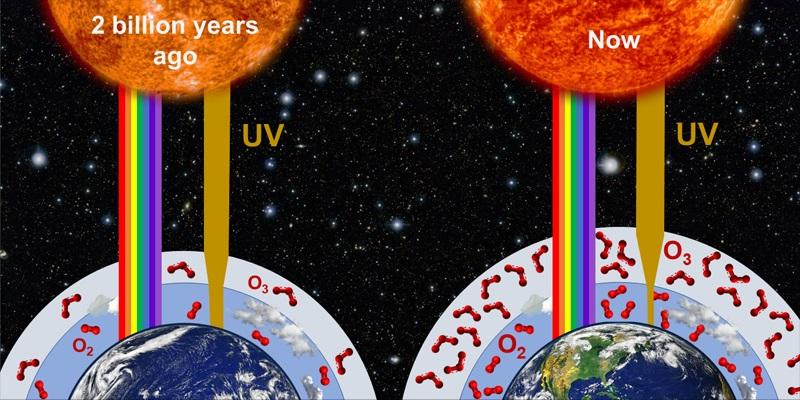

The researchers think that greater levels of UV radiation could have hit Earth because of a weaker ozone layer, which absorbs the radiation. The amount of ozone in our atmosphere depends on a number of factors and chemical reactions, but oxygen levels play a major role in the formation of ozone.

Previously, it was thought that atmospheric oxygen levels of around 1 percent of today's levels would produce enough ozone to keep harmful UV radiation away. Now, using advanced computer climate simulations, the team suggests that the key oxygen level might be more like 5-10 percent.

There are questions over how much UV light has got through to Earth's surface over the past 2 billion years. (Greg Cooke/Royal Society Open Science)

There are questions over how much UV light has got through to Earth's surface over the past 2 billion years. (Greg Cooke/Royal Society Open Science)

In other words, for long stretches of time across the past 2.4 billion years when we thought there was enough ozone around to significantly block UV rays, that might not have been the case. As the researchers explain, that has a knock-on effect on life on Earth and even which organisms can flourish.

"If our modeling is indicative of atmospheric scenarios during Earth's oxygenated history, then for over a billion years the Earth could have been bathed in UV radiation that was much more intense than previously believed," says Cooke. "This may have had fascinating consequences for life's evolution."

The increased levels of UV radiation may have been responsible for at least one mass extinction across the ages, the researchers say, which matches with the findings of some previous studies.

This type of radiation has the potential to cause damage and destruction at the molecular level, and the authors of the new study are calling for the timeline of ozone levels in Earth's atmosphere to be revisited. Multiple factors, including the changing luminosity of the Sun, need to be taken into account.

Around 400 million years ago, oxygen levels in the atmosphere got up to modern-day standards, and more complex life forms began to evolve, leading to the wide biodiversity in evidence across the planet today.

"It is not precisely known when animals emerged, or what conditions they encountered in the oceans or on land," says Cooke.

"However, depending on oxygen concentrations, animals and plants could have faced much harsher conditions than today's world. We hope that the full evolutionary impact of our results can be explored in the future."

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.