What gives rise to human consciousness? Are some parts of the brain more important than others?

Scientists began tackling these questions in more depth about 35 years ago. Researchers have made progress, but the mystery of consciousness remains very much alive.

In a recently published article, I reviewed over 100 years of neuroscience research to see if some brain regions are more important than others for consciousness. What I found suggests scientists who study consciousness may have been undervaluing the most ancient regions of human brains.

Consciousness is usually defined by neuroscientists as the ability to have subjective experience, such as the experience of tasting an apple or of seeing the redness of its skin.

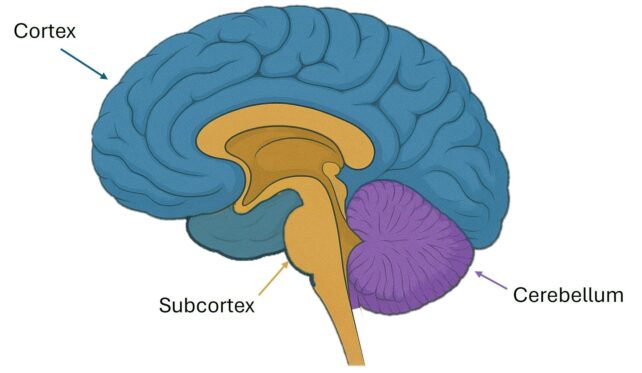

The leading theories of consciousness suggest that the outer layer of the human brain, called the cortex (in blue in figure 1), is fundamental to consciousness. This is mostly composed of the neocortex, which is newer in our evolutionary history.

The human subcortex (figure 1, brown/beige), underneath the neocortex, has not changed much in the last 500 million years. It is thought to be like electricity for a TV, necessary for consciousness, but not enough on its own.

There is another part of the brain that some neuroscientific theories of consciousness state is irrelevant for consciousness. This is the cerebellum, which is also older than the neocortex and looks like a little brain tucked in the back of the skull (figure 1, purple).

Brain activity and brain networks are disrupted in unconsciousness (like in a coma). These changes can be seen in the cortex, subcortex, and cerebellum.

What brain stimulation reveals

As part of my analysis, I looked at studies showing what happens to consciousness when brain activity is changed, for example, by applying electrical currents or magnetic pulses to brain regions.

These experiments in humans and animals showed that altering activity in any of these three parts of the brain can alter consciousness. Changing the activity of the neocortex can change your sense of self, make you hallucinate, or affect your judgment.

Changing the subcortex may have extreme effects. We can induce depression, wake a monkey from anaesthesia, or knock a mouse unconscious. Even stimulating the cerebellum, long considered irrelevant, can change your conscious sensory perception.

However, this research does not allow us to reach strong conclusions about where consciousness comes from, as stimulating one brain region may affect another region. Like unplugging the TV from the socket, we might be changing the conditions that support consciousness, but not the mechanisms of consciousness itself.

So I looked at some evidence from patients to see if it would help resolve this dilemma.

Damage from physical trauma or lack of oxygen to the brain can disrupt your experience. Injury to the neocortex may make you think your hand is not yours, fail to notice things on one side of your visual field, or become more impulsive.

People born without the cerebellum, or the front of their cortex, can still appear conscious and live quite normal lives. However, damaging the cerebellum later in life can trigger hallucinations or change your emotions completely.

Harm to the most ancient parts of our brain can directly cause unconsciousness (although some people recover) or death. However, like electricity for a TV, the subcortex may be just keeping the newer cortex "online", which may be giving rise to consciousness. So I wanted to know whether, alternatively, there is evidence that the most ancient regions are sufficient for consciousness.

There are rare cases of children being born without most or all of their neocortex. According to medical textbooks, these people should be in a permanent vegetative state. However, there are reports that these people can feel upset, play, recognize people, or show enjoyment of music. This suggests that they are having some sort of conscious experience.

These reports are striking evidence that suggests maybe the oldest parts of the brain are enough for basic consciousness. Or maybe, when you are born without a cortex, the older parts of the brain adapt to take on some of the roles of the newer parts of the brain.

There are some extreme experiments on animals that can help us reach a conclusion. Across mammals – from rats to cats to monkeys – surgically removing the neocortex leaves them still capable of an astonishing number of things. They can play, show emotions, groom themselves, parent their young, and even learn. Surprisingly, even adult animals that underwent this surgery showed similar behavior.

Altogether, the evidence challenges the view that the cortex is necessary for consciousness, as most major theories of consciousness suggest. It seems that the oldest parts of the brain are enough for some basic forms of consciousness.

The newer parts of the brain – as well as the cerebellum – seem to expand and refine your consciousness. This means we may have to review our theories of consciousness. In turn, this may influence patient care as well as how we think about animal rights. In fact, consciousness might be more common than we realized.![]()

Peter Coppola, Visiting Researcher, Cambridge Neuroscience, University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.